Jesús Rafael Soto facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

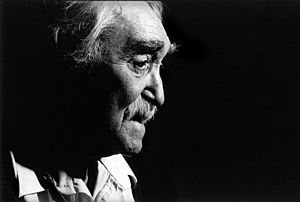

Jesús Rafael Soto

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 5, 1923 |

| Died | January 14, 2005 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | Venezuelan |

| Education | Escuela de Artes Plasticas y Aplicadas |

|

Notable work

|

Penetrables |

| Movement | Kinetic and Op Art |

Jesús Rafael Soto (born June 5, 1923 – died January 17, 2005) was a famous Venezuelan artist. He was known for his unique sculptures and paintings that often played with how we see things. His art is called Op Art and Kinetic Art.

You can find his amazing artworks in major museums around the world. These include the Tate in London, the Museum Ludwig in Germany, and the MoMA in New York. There's even a main art museum in his hometown in Venezuela named after him to honor his work!

Contents

Early Life and First Steps in Art

Jesús Rafael Soto was born in Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela. He was the oldest of four children. His father, Luis Garcia Parra, was a violin player. From a young age, Soto wanted to help his family. He found art the most interesting way to do this. He enjoyed playing the guitar and copying famous artworks from books and magazines.

When he was 16, Soto started his art career by painting posters for cinemas in Ciudad Bolívar. He once said that at that time, the only artists he knew were those who painted letters. His family was happy because he could earn money, even if it was just painting letters.

In 1938, Soto joined a student group interested in surrealism. He even published some poems in a local newspaper that surprised society. In this group, Soto learned about automatic writing and charcoal drawing. He became very good at drawing portraits. Thanks to a petition signed by many people, including the bishop, he received a scholarship to study art.

Learning and Growing as an Artist

In 1942, Soto received a scholarship to study at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Artes Aplicadas (Plastic and Applied Arts School) in Caracas. He finished his studies in 1947. There, he took classes in "pure art" and learned how to teach art history. The school's director, Antonio Edmundo Monsanto, was very important for Soto and other Venezuelan artists. Monsanto often brought new ideas from other countries to his students, including the latest art style called cubism.

Soto was greatly impressed when he first saw a picture of a still life by Georges Braque at the art school. He said it was amazing how "the color started to separate off the form." This made him think about showing many different viewpoints in his art. For Soto, this was a big turning point.

Moving to Paris and New Ideas

After Soto graduated, he became the director of the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Maracaibo from 1947 to 1950. While teaching there, he received a government grant to travel to France. He then moved to Paris, a major art city.

In France, Soto discovered the works of Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian. Mondrian's ideas especially made Soto think about making art that seemed to move. Soto wanted to create a new kind of movement in three-dimensional art. This led him to work with other artists like Yaacov Agam, Jean Tinguely, and Victor Vasarely. They were all interested in similar ideas and showed their art at places like the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles and the Galerie Denise René.

Soto's Artistic Journey

Soto's art changed a lot over time. At first, he painted in a style similar to Post-Impressionism. Later, he became interested in Cubism. After learning about artists like Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, and the Constructivists, Soto started to experiment with how our eyes see things. This led him to create op art and then art that was more than just flat pictures.

Early Experiments with Repetition

In the 1950s, Soto experimented with what he called serial art. This meant repeating shapes and elements in his artworks. He wanted to show that art could be a small part of an endless reality. His art could be repeated without changing its main structure, having no clear beginning or end. He used ideas from math and music to create this "serial art."

Adding Real Movement and Time

The next big step for Soto was to add real movement and time into his art. He wanted his artworks to be objects that created "real" situations, not just flat pictures. As people walked around his art, they would see optical effects that seemed to vibrate. This brought time and real movement into the artwork itself. In his piece Dos cuadrados en el espacio (Two Squares in Space) from 1953, Soto started using the square shape, which was important to Malevich.

In Desplazamiento de un cuadro transparente (Displacement of a Transparent Square) from 1953–54, he created a feeling of space on a flat surface. He later made this three-dimensional by layering two or more clear Plexiglas sheets. These sheets had straight or curved lines painted on them. As viewers moved, the lines seemed to change, inviting people to be part of the art. This work showed how our eyes can be tricked into seeing space differently.

In 1955, Soto took part in an important exhibition called Le Mouvement (The Movement) at the Denise René gallery in Paris. Other artists like Marcel Duchamp were also there. This exhibition led to a special paper called the ‘Yellow Manifest’ about kinetic art. Kinetic art is all about movement and how viewers interact with the art. After this show, the kinetic art movement became very popular in Europe and Latin America.

Making Forms Disappear

Soto found that when he layered different surfaces, his art created optical vibrations. This led to a new idea: solid objects could seem to disappear or "dematerialize" in our eyes. This happened for the first time in his work Permutación (Permutation) from 1956. In other works like Estructuras cinéticas de elementos geométricos (Kinetic Structures of Geometric Elements) (1955-57) and Armonía transformable (Transformable Harmony) (1956), he added color. He layered different Plexiglas sheets with colored frames, creating even more vibrating effects. This made the art feel truly three-dimensional. As his ideas grew, Plexiglas became a limit, and he looked for new ways to show vibration.

Creating a New Visual Experience

Soto also wanted his art to be big enough for people to walk through and to fit into buildings. This is how he created Estructura Cinética (Kinetic Structure) in 1957. The lines he used to draw on Plexiglas became real metal rods welded together. Soto's artworks became large objects that visitors could actually enter and experience.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Soto had developed his main ideas. He believed that matter and space were different forms of energy. Works like Escritura (Writing) and Muro de Bruselas (Wall of Brussels), both from 1958, already showed all the elements he would develop later.

Soto described his art as "totally abstract." He said he didn't copy nature but instead focused on the basic properties of reality. For him, his artworks were "signs" of something else, not just objects themselves. He wanted people to understand that the art in front of them was a clue to a deeper idea.

The Fullness of Space

All of Soto's work aimed to show his idea of the world as a reality too big for humans to fully grasp. He believed energy and space were essential parts of nature. His goal was to show these ideas in all their complexity.

Soto explained his famous Penetrables (Penetrables) artworks: "When you enter a penetrable, you feel like you're in a swirl of light, a total fullness of vibrations. The Penetrable makes this fullness real. I make people move through it so they can feel the 'body' of space. It's a way of making something that exists, but is invisible, feel real. Reality is everywhere and fills the whole universe. There is no emptiness anywhere. This is my main idea."

Soto's Impact on Art

Soto helped create a new kind of art that went beyond traditional painting and sculpture. By inviting people to walk through or interact with his art, he made the experience more exciting and engaging. He had partners in this movement. For example, Carlos Cruz-Diez focused on how our eyes see colors. One of his series, Fisicromias (Physiochromies), shows how colored light moves and changes as we look at it. Another artist, Alejandro Otero, also explored color perception and movement in his Colortions (Rhythmicolors) series, using vertical lines to control colors.

Jesús Rafael Soto passed away in 2005 in Paris and is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse.

Why Soto's Art Matters

Like many Venezuelan artists of his time, Jesús Rafael Soto and Carlos Cruz-Diez believed their art was a way to solve problems they saw in the art world. They wanted to create art that was more universal, meaning it could be understood by everyone, everywhere. Their willingness to explore new ideas and take a universal approach helped enrich the art world. This was also their way of adding something new to Latin American art, which they felt was missing.

Soto and Cruz-Diez believed that painting should respond to the current world. They felt that other art was "academic" or "outdated." As Alejandro Otero once said, it was "the work of a man hiding behind time."

Where to See His Art

In 1973, the Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art opened in Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela. It has a large collection of his work. The building was designed by Venezuelan architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva. Many of the artworks in this museum are connected to electricity so they can move, which is very cool!

Soto's works are also in many other famous museums around the world, including:

- Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia

- Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium

- Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil

- Musée d'Art Contemporain de Montréal, Canada

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

- Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany

- The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

- Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Roma, Italy

- Fukuoka Art Museum, Japan

- Museo Rufino Tamayo, Mexico

- Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

- Tate Gallery, London, United Kingdom

- The Museum of Modern Art, New York, U.S.A.

- Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, Venezuela

Art in Public Spaces

Soto also created many large artworks that are part of buildings and public spaces. These are called "environmental integrations" because they become part of the environment around them. Here are a few examples:

- 1957: "Structure cinétique" in Ciudad Universitaria, Caracas, Venezuela.

- 1958: "Wall of Brussels" and "Tour de Bruxelles" for the Universal Exhibition in Brussels, Belgium (now in Caracas, Venezuela).

- 1967: "Volume suspendu" for Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada.

- 1969: "Mur cinétique" at UNESCO, Paris, France.

- 1972-82: Artworks for the Complejo Cultural Teresa Carreño in Caracas, Venezuela.

- 1973-95: A "Penetrable" in Parque García Sanabría, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain.

- 1997: The famous "Esfera de Caracas" (Caracas Sphere) on the Francisco Fajardo motorway in Caracas, Venezuela.

- 1997: "Penetrable of Tongyoung" in Tongyoung Nammang Open Air Sculpture Park, Korea.

- 1998-99: "La esfera de Margarita" in Porlamar, Margarita Island, Venezuela.

See also

In Spanish: Jesús Rafael Soto para niños

In Spanish: Jesús Rafael Soto para niños

- National Prize of Plastic Arts of Venezuela