Jiří Stránský facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

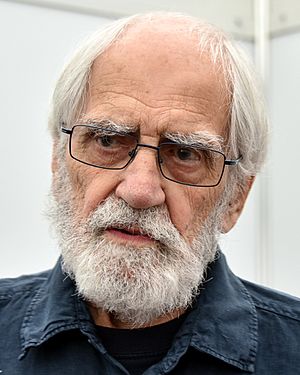

Jiří Stránský

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | August 12, 1931 Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Died | May 29, 2019 (aged 87) Prague, Czech Republic |

| Occupation | author, playwright, screenwriter, translator, |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Notable works | Štěstí, (Happiness) Zdivočelá země, (The land gone wild) Přelet, (Flight) Perlorodky, (Pearls) Tóny, (Tones) Balada o pilotovi,(Ballad of the pilot) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Antonie Formanová (granddaughter) |

Jiří Stránský (born August 12, 1931 – died May 29, 2019) was a Czech writer, who wrote plays, movie scripts, and translated books. He was also a brave person who stood up for human rights. He was unfairly imprisoned twice by the government that ruled his country at the time.

In 1953, he was arrested and sentenced to eight years of hard labor. He was set free in 1960. In 1974, he was arrested again, but this time he was released after only a year and a half. While he was imprisoned, he met other writers. These meetings encouraged him to become a writer himself.

After the government changed in 1989, he became a well-known author. He also led the international part of the Czech Literary Fund. In 1992, he became the President of the Czech section of International PEN, an organization for writers. He also chaired the council of the National Library from 1995 to 1998.

Jiří Stránský was one of the first people to sign the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism. This declaration spoke about the wrongs committed by the communist government. He also signed Charter 77, which was a brave document asking for human rights in Czechoslovakia.

Contents

A Notable Czech Figure

Stránský is a very important person to the Czech people. He bravely stood up against unfair rules and injustice before 1989. He was also very creative, writing books, movie scripts, plays, and poems. He even translated other people's works. Stránský also achieved things as a scout.

His importance in Czech society also comes from his family. Many of his relatives were important figures in what is now the Czech Republic. Stránský was the grandson of Jan Malypetr, a famous Czech politician. His father, Karel Stránský, was a lawyer. He was also related to Antonín Benjamin Svojsík, who started Czech Scouts.

His family, especially his father, also resisted the unfair communist government. Because of this, and his own actions, Jiří was not allowed to finish school. Before 1989, he was wrongly accused of crimes against the government of Czechoslovakia. He was then put in prison for different lengths of time. But after the government changed in 1989, Stránský became very successful. He received many important awards for his art and for his strong resistance to unfair rule. Many of his popular works were published widely and turned into films, TV shows, and radio plays.

Early Life and Scouting

Like most young people in Czechoslovakia, scouting and sokol were a big part of Jiří's life, just like school. His ancestor was a famous founder of scouting in the Czech region, bringing the popular British style there. His father was also important in their community's Sokol group as a mayor. Jiří really valued his time in these groups. He said the training he got helped him survive later in life. In the scouts, he was given the name "Jira."

Jiří Stránský was active in other ways too. When he was just fourteen, Jiří joined the May Uprising of 1945. This was a movement to resist the government at the time. He received an award for his bravery, being the youngest person to join the fight against the government.

Because of his brave actions, or his family's refusal to agree with the government's ideas, he was not allowed to finish school. So, he had to work many different jobs. Then, when he was twenty-one, he was wrongly accused of being a spy and was put in prison.

First Imprisonment: Becoming a Writer

Jiří Stránský's first time in prison happened because a friend wrongly accused him. His friend was pressured to give information about people he knew. So, he made up a story about Jiří, saying he was a spy. At the time, Jiří was twenty-one years old. This meant his usual 16-year sentence was cut in half to 8 years. He was sentenced to do hard labor, mining for uranium.

Looking back, he would joke that uranium mining was not the best kind of forced labor! But it was during those long, hard days that he found inspiration to become a writer. Everything he saw, everything he witnessed, and everyone he met made him want to write down all the details as stories. Luckily, he also spent time with some important Catholic writers like František Křelina, Josef Knap, and Jan Zahradníček. Even though they didn't really support his writing interest (because they were in prison for their own writing), he still wrote in secret. With help from a civilian worker at the uranium mine, he managed to write short pieces that were secretly sent outside. After he was released, he used his notes to write "Happiness," which was finally published in 1968.

During his first prison sentence, Jiří had to travel to many labor camps and prisons. He started in Pankrák, then went to Ilava prison, Vykmanov camp, Svatopluk u Horní Slavoka camp, and Vojna camp. While at Vojna, he joined a hunger strike and was moved again. Jiří was set free from prison in 1960.

Until 1974, when he was imprisoned again, he worked as a skilled laborer. He lived in many places and started a family. Jiří married Jitka, whom he had known before his first imprisonment. They had two children, a daughter named Klárka and a son named Martin. Jiří jokingly said he helped build the stadium in Podolí, which is still standing today! Jiří also managed to get some of his short stories published. One story, "Vašek," caught the eye of film director Martin Frič, who hired him as an assistant director. Soon after, he also worked as an assistant director for Hynek Bočan. Even though he wasn't allowed to have a permanent job, he managed to work at a gas station. The gas station was near a film studio, and many of his customers worked there. This way, Jiří unofficially helped the studio by talking to the people he met at the gas station. This place was later called the "Intellectual Gas Station."

Second Imprisonment

Stránský said his second time in prison happened because his activities at the "Intellectual Gas Station" were discovered. He was arrested because of a false accusation of taking money that wasn't his. He was sentenced the next year to serve only two years.

"Doctor of Prison Sciences"

After 1989, Jiří Stránský became a popular writer, playwright, and artist. People often called him "Dr. Jiří Stránský," even though he never finished school or got a degree. So, at an event he hosted for the Franz Kafka Society, he decided to fix this mistake. He created his own special honorary degree: "Doctor of Prison Sciences," or a PhD in Prison Sciences.

He joked that he was a certified expert in prisons after spending many years in them. He explained, "Now, the smartest people of the nations are here in these camps and prisons. And, really, this [his time in prison] university lasted for over seven years. I listened to countless lectures on philosophy, art, and other subjects." He truly made the most of his time in prison, learning from the wisdom of his fellow prisoners, like Honza Zahradníček. Stránský remembered a time when he and other prisoners met to hear an art historian, who was also a prisoner, talk about art and beauty. He mentioned works by Velasquez and other impressionist artists. To share the art, Stránský and the other prisoners in this secret art history class arranged for a civilian worker to buy postcards with famous paintings from the National Gallery in Prague.

A Quote from Jiří Stránský

"I was raised so that one of our slogans was: We will not make them happy. Translated into normal language: We will not please anyone who humiliates us by showing him that we are humiliated. Others say nobly, 'I won't bend, I don't kneel'. We just had to say, 'We will not make them happy'."

Works

- Za plotem, (Behind the Fence), written in prison (1953–1960), published 1999

- Štěstí, (Happiness), 1969, most copies were taken and destroyed by the communists, it was released in 1990

- Zdivočelá země, (The land gone wild), 1970, made into a film in 1997

- Aukce, (Auction), 1997, a follow-up to Zdivočelé země, 1989

- Přelet, (Flight), 2001

- Povídačky pro moje slunce, (Stories for my sun), 2002

- Tichá pošta, (Silent post), 2002

- Povídačky pro Klárku, (Stories for Klara [his daughter]), 2004

- Perlorodky, (Pearls), 2005

- Srdcerváč, 2005

- Stařec a smrt, 2007

- Oblouk, 2009

- Tóny, (Tones) 2012 – a short novel

- Balada o pilotovi, (Ballad of the pilot) 2013 – a short novel telling the story of Karel Balík, his wife's father

- Štěstí napodruhé, 2019

Short Stories

- "Náhoda," 1976

- "Vánoce," ("Christmas"), 1976

- "Přelet," ("Flight"), 1976

- "Dopisy bez hranic," (Letters without Borders, with Lasica and Stránský), 2010

Plays

- Latríny, 1972

- Labyrint, 1972

- Claudius a Gertruda, which first showed on December 7, 2007, by the Kašpar theater group, directed by Jakub Špalek

Films Based on His Work

- Bumerang, 1996, directed by Hynek Bočan

- Zdivočelá země, 1997

- Zdivočelá země, TV series 1997–2001, directed by Hynek Bočan

- Uniforma, 2001, directed by Hynek Bočan

- Žabák, (Frog), 2001, directed by Hynek Bočan

- Kousek nebe, (A piece of heaven), 2005, directed by Petr Nikolaev

- Balada o pilotovi, (Ballad of the pilot, also called A Pilot Tale), 2018, directed by Ján Sebechlebský

Awards

- 2015: Knight of Czech Culture - An award from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic

- 2015: Arnošt Lustig Award

- Medal of Merit (Czech Republic)

- Artis Bohemiae Amicis Medal

- Karel Čapek Prize

- 1 June Award

- Order of the Silver Wolf (2011)

- Memory of Nation Award (2013)

See also

In Spanish: Jiří Stránský para niños

In Spanish: Jiří Stránský para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |