John Struthers (anatomist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

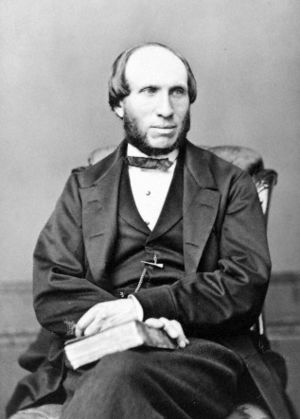

John Struthers

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 21 February 1823 Brucefield, Dunfermline

|

| Died | 24 February 1899 (aged 76) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Resting place | Warriston Cemetery |

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Anatomist, professor |

| Employer | U. Edinburgh, U. Aberdeen |

| Spouse(s) | Christina Margaret Alexander |

| Children | Three sons, four daughters |

| Parent(s) | Alexander, Mary (Reid) |

Sir John Struthers (born 1823, died 1899) was a very important Scottish doctor and professor. He became the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen. He was a fantastic teacher and a strong leader who improved the places he worked.

Struthers loved studying anatomy, which is the study of the body's structure. He was always looking for the biggest and best animal specimens, like whales, to dissect. He even bothered his co-workers to get more money and space for his amazing collection. Later, he gave his collection to Surgeon's Hall in Edinburgh.

Scientists know him for a special ligament in the human arm that is named after him. His work on this rare body part, called the ligament of Struthers, caught the attention of Charles Darwin. Darwin used Struthers' findings in his book Descent of Man to help show that humans and other mammals share a common ancestor.

Many people knew Struthers because he dissected the "Tay Whale". This huge humpback whale appeared in the Firth of Tay, was hunted, and then shown across Britain. Struthers worked hard to dissect it and collect its bones. He later wrote a whole book about it.

In the medical world, he was famous for changing how anatomy was taught. He wrote many important papers and books. He was also very good at running his medical school. For all his hard work, he received many top honors, including a knighthood.

Contents

Early Life and Family

John Struthers was born on February 21, 1823, in Brucefield, near Dunfermline, Scotland. His father, Alexander Struthers, was a rich mill owner and linen merchant. John grew up in a large stone house with big gardens.

He was one of six children, with three brothers and three sisters. The boys had private tutors at home who taught them many subjects. They enjoyed outdoor activities like boating, skating, riding ponies, and swimming.

Both of John's older brothers also studied medicine. His older brother, James, became a doctor at Leith Hospital. His younger brother, Alexander, sadly died from cholera while working as a doctor in the Crimean War.

Medical Career and Teaching

Struthers studied medicine at Edinburgh University and won many awards. He earned his medical degree (M.D.) in 1845. Soon after, he and his brother James were allowed to teach anatomy in Edinburgh. Their courses were recognized by medical schools across Britain.

He worked his way up at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, starting as a surgical assistant. He loved anatomy so much that one day in 1843, he was so focused on a dissection that he missed a big street parade outside! He later became a lecturer of anatomy at the University of Edinburgh.

In 1863, Struthers became the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen. This was a very important government-recognized teaching position. Many famous doctors and politicians supported his application for the job. His family then moved to Aberdeen.

Struthers taught at Aberdeen for 26 years. During this time, he completely changed how anatomy was taught. He made the Aberdeen medical school much better. He also created a large museum of anatomy. He worked hard to get specimens for his museum, often paying for them himself.

He arranged the specimens so students could compare the anatomy of different animals. He wanted to show how animals had changed over time, supporting the idea of evolution. For example, he showed how the arm of a human, the wing of a bird, and the flipper of a whale are all similar forelimbs.

Struthers was always asking the university for more space and money for his museum. He even went to great lengths to get specimens. Once, he borrowed a crocodile skeleton and kept it for ten years! He published about 70 papers on anatomy. He also gave popular public lectures on Saturday evenings.

He had a big impact on medical education in Britain. In 1890, he set up a system where students first studied basic sciences like anatomy for three years. This system lasted for a very long time. Struthers believed that doctors needed to understand the basic sciences to truly understand diseases and their treatment. He famously told his students:

Unless you are well informed in the foundation sciences and principles, you may practise your profession, but you will never understand disease and its treatment; your practice will be routine, the unintelligent application of the dogmas and directions of your textbook or teacher.

Scientific Discoveries

Evolution and Struthers' Ligament

Struthers was one of the first people to support the theory of evolution. He spoke publicly about it and wrote to Charles Darwin about his observations.

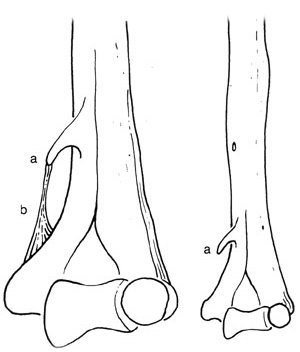

He was very interested in unusual body variations, like extra toes. He collected many such specimens. Struthers described a rare extra band of tissue in the human arm, which he called the "Ligament of Struthers". This ligament is found in about 1% of people and can be passed down in families.

This ligament is important because it has no real use in humans. However, it comes from a structure that was very useful in other mammals, like marsupials and carnivores. In those animals, it's an opening in the bone that important nerves and arteries pass through. Struthers noticed that when humans had this ligament, their nerve and artery also passed through it.

Darwin used this as evidence that humans and other mammals shared a common ancestor. He wrote about Struthers' work in his book Descent of Man (1871):

In some of the lower Quadrumana, in the Lemuridae and Carnivora, as well as in many marsupials, there is a passage near the lower end of the humerus, called the supra-condyloid foramen, through which the great nerve of the fore limb and often the great artery pass. Now in the humerus of man, there is generally a trace of this passage, which is sometimes fairly well developed, being formed by a depending hook-like process of bone, completed by a band of ligament. Dr. Struthers, who has closely attended to the subject, has now shewn that this peculiarity is sometimes inherited, as it has occurred in a father, and in no less than four out of his seven children. When present, the great nerve invariably passes through it; and this clearly indicates that it is the homologue and rudiment of the supra-condyloid foramen of the lower animals. Prof. Turner estimates, as he informs me, that it occurs in about one per cent of recent skeletons. But if the occasional development of this structure in man is, as seems probable, due to reversion, it is a return to a very ancient state of things, because in the higher Quadrumana it is absent.

Studying Whale Anatomy

Living in Aberdeen, a city by the sea, gave Struthers the chance to study whales that washed ashore. In 1870, he studied a blue whale from Peterhead. He even brought the whole skeleton of a sei whale back to his department at Aberdeen. For a hundred years, it hung from the ceiling in the hall!

He actively collected many different animal examples for his museum. He wanted to use them to show Darwin's ideas about evolution. Struthers was very enthusiastic about zoology, the study of animals. He often asked his colleagues at the University of Aberdeen for money and space to get and keep his collection.

Dissecting the Famous Tay Whale

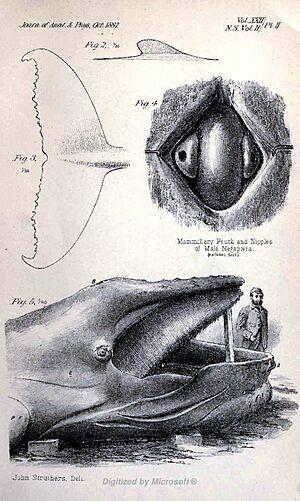

Struthers became well-known to the public for dissecting the "Tay Whale", one of his biggest specimens.

In late December 1883, a humpback whale appeared in the Firth of Tay near Dundee. Many people came to see it. It was hunted but escaped. A week later, it was found dead and pulled onto the beach near Aberdeen. Struthers quickly went to see it. He measured it as 40 feet long with a tail 11 feet 4 inches wide.

Struthers couldn't dissect it right away because a local businessman, John Woods, bought the whale. Woods took it to his yard in Dundee, where 12,000 people paid to see it on the first Sunday!

Struthers was only allowed to dissect the whale after it had started to decompose too much for public viewing. He was used to working on smelly carcasses. His dissecting room was even said to smell like a whaling ship! The dissection was made difficult because John Woods allowed the public to watch Struthers work, with a military band playing in the background. Snow also made the work harder.

Struthers managed to remove most of the skeleton. Woods then had the flesh preserved so the whale could be stuffed and shown on a profitable tour. After months of waiting, Struthers finally got the skull and the rest of the skeleton on August 7, 1884. Over the next ten years, Struthers wrote seven articles about the whale's anatomy. He published a complete book about it in 1889.

Later Life and Honors

Struthers married Christina Margaret Alexander in 1857. She came from a medical family too. They had three sons and four daughters. All three of their sons also became doctors. One son, John William Struthers, followed in his father's footsteps, working at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and becoming president of the Royal College of Surgeons.

When Struthers retired from the University of Aberdeen, he moved back to Edinburgh. He was buried in Warriston Cemetery in Edinburgh in 1899.

Struthers received many awards for his work. The University of Glasgow gave him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 1885. He became president of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh. He was a member of the General Medical Council from 1883 to 1891. In 1895, he became president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Finally, in 1898, Queen Victoria made him a knight (Sir John Struthers) for his great service to medicine.

The Struthers Medal at Glasgow University is named in his honor.

Images for kids

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |