Joralemon Street Tunnel facts for kids

|

|

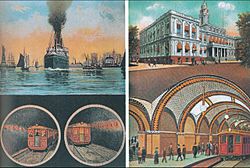

| 1913 postcard showing the tunnel and City Hall station | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | IRT Lexington Avenue Line (4 and 5 train) |

| Location | East River between Manhattan and Brooklyn, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°41′49″N 74°00′26″W / 40.69694°N 74.00722°W |

| System | New York City Subway |

| Operation | |

| Operator | Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

| Technical | |

| Length | 6,550 feet (2,000 m) |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Width | 16.67 feet (5.1 m) (outside) 15.5 feet (4.7 m) (inside) |

The Joralemon Street Tunnel is a very important part of the New York City Subway system. It has two tubes that carry the IRT Lexington Avenue Line (which uses the 4 and 5 train train) under the East River. This tunnel connects Bowling Green Park in Manhattan to Brooklyn Heights in Brooklyn, New York City.

This tunnel was the first underwater subway tunnel to connect Manhattan and Brooklyn. It was a big step forward for transportation in New York City. The tunnel is about 6,550 feet (2,000 m) long and 15.5 feet (4.7 m) wide inside. It was built using a special method called the "shield method." The deepest part of the tunnel is about 91 to 95 feet (28 to 29 m) below the water level of the East River.

Construction started in 1903 and the tubes were finished by 1907. Even with some challenges during building, the first train went through in November 1907. The tunnel officially opened for passengers on January 9, 1908. In 2006, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places because of its historical importance.

Contents

What is the Joralemon Street Tunnel?

The Joralemon Street Tunnel has two parallel tubes that go under the East River. It connects the boroughs of Manhattan in the west and Brooklyn in the east. When it was finished in 1908, it was the first subway tunnel between these two busy areas.

The tunnel was built as part of the second major contract for the first New York City Subway line. The tubes stretch from South Ferry in Lower Manhattan to Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights. The tunnel's path curves a bit on both sides of the river. The main engineer for this project was William Barclay Parsons, who designed much of the early subway system.

How long and deep is the tunnel?

Each tube of the tunnel is about 6,550 feet (2,000 m) long. The part that goes under the river is about 4,500 feet (1,400 m) long. The tunnels are 16.67 feet (5.1 m) wide on the outside and 15.5 feet (4.7 m) wide on the inside. The two tubes are usually about 28 feet (8.5 m) apart.

The lowest points of the tubes are about 91 to 95 feet (28 to 29 m) below the average high water level of the East River. About 700 feet (210 m) of the tunnel in Brooklyn is actually above the river's water level. The Manhattan side of the tunnel was built through solid rock, but the Brooklyn side was built through sandy ground.

How was the tunnel built?

The tunnels are lined with strong cast-iron "rings." These rings are 22 inches (560 mm) wide and are made of plates that form a perfect circle. After the rings were put in place, they were covered with concrete. Walls with special spaces for cables were also built along each tube. Workers also installed pipes and drainage systems to keep the tunnel dry.

Associated structures

The Manhattan end of the tunnel connects to the Bowling Green station of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line. North of Bowling Green, the subway goes under Broadway to join the original subway line. The Brooklyn end of the tunnel is at Joralemon and Clinton Streets. Here, a "cut-and-cover" tunnel (meaning it was dug from the surface and then covered) connects to the Borough Hall station of the IRT Eastern Parkway Line.

Two special shafts were built during the tunnel's construction. One was in Manhattan at South Ferry, and the other was in Brooklyn at Henry and Joralemon Streets. The South Ferry shaft became a ventilation shaft, which helps air circulate in the tunnel. It has a 10-foot-high (3.0 m) building around it. The Henry Street shaft was later filled in.

A very interesting ventilation and emergency exit shaft was built inside a regular-looking house at 58 Joralemon Street, near Willow Street in Brooklyn. This house was built in 1847, but the subway company bought it in 1907 and changed its inside to serve as a ventilation plant.

History of the Tunnel

Planning the subway tunnel

Plans for New York City's first subway line began in 1894. Engineers, led by William Barclay Parsons, designed the subway routes. The first contract for building the subway was signed in 1900. This contract covered a line from New York City Hall to the Upper West Side and into the Bronx.

Soon after, engineers looked into extending the subway south from City Hall to South Ferry, and then across the East River to Brooklyn. In 1901, a route was chosen that would extend the subway to the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s Flatbush Avenue station in Brooklyn. This route would go under the East River and then under Joralemon Street, Fulton Street, and Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. This second part of the subway project, known as Contract 2, was officially agreed upon in September 1902.

Building the Joralemon Street Tunnel

Construction on the Manhattan side of the tunnel started on March 4, 1903. Work on the Brooklyn side began a few months later, on July 10, 1903. The project was expected to cost about $10 million.

Workers dug construction shafts at South Ferry and Joralemon Street. They used six special machines called "tunneling shields." These shields were pushed forward, digging the tunnel at a rate of about 5 to 12 feet (1.5 to 3.7 m) per day. The work was done in a pressurized environment, meaning the air inside the tunnel was kept at a higher pressure to prevent water and mud from rushing in. This required special "air locks" for workers to enter and exit.

After the tunnels were dug, cast-iron rings were put in place to form the tunnel walls. These rings were then covered with concrete. Sometimes, the cast-iron plates cracked during placement, but engineers believed the tunnels were still safe.

During construction, the digging caused some sandy soil to shift in Brooklyn. This damaged some buildings along the tunnel's path. The city had to pay money to repair these houses. There were also several accidents during construction, including cave-ins and a "blowout" where a worker was pushed through mud by air pressure, though he survived.

Engineers also discovered that parts of the tunnel's ceiling had flattened, and some sections in Brooklyn had gone deeper than planned. To avoid more delays, the contractors decided to finish the tunnel and then rebuild the problem sections later. About 1,957 feet (596 m) of the northern tube and 962 feet (293 m) of the southern tube were rebuilt.

The two parts of the northern tube met on December 15, 1906, and the southern tube sections met on March 1, 1907. The first test train, carrying officials and engineers, traveled through the Joralemon Street Tunnel to Brooklyn on November 27, 1907.

Operating the tunnel

The Joralemon Street Tunnel and the Borough Hall station officially opened to the public on January 9, 1908. There were ceremonies, firecrackers, and music to celebrate!

At first, the tunnel was used by express trains. The opening of the Joralemon Street Tunnel, along with new bridges like the Williamsburg Bridge and Manhattan Bridge, helped reduce traffic on the old Brooklyn Bridge and the East River ferries. Before these tunnels and bridges, ferries were the only way for people to travel between Manhattan and Brooklyn.

In 1913, new plans called the "Dual Contracts" were made to expand the subway system. As part of these plans, the original subway line was split into an "H"-shaped system. By 1918, all trains using the Joralemon Street Tunnel became part of the Lexington Avenue Line. Another tunnel, the Clark Street Tunnel, opened in 1919, providing more subway service to Brooklyn.

In the later 1900s, a few trains derailed (went off the tracks) in the Joralemon Street Tunnel. In 1965 and 1984, trains derailed, but luckily, no one was seriously hurt in either incident.

The Joralemon Street Tunnel was recognized for its historical importance in 2006 when it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused severe flooding in New York City. The Joralemon Street Tunnel was one of seven subway tunnels under the East River that flooded. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) worked quickly to drain the water and restore service. The tunnel was cleared in just two days and reopened within a week. More extensive repairs were done on the tunnels between 2016 and 2017, costing $75 million, to make sure they stay safe and reliable.

See also

In Spanish: Túnel de la Calle Joralemon para niños

In Spanish: Túnel de la Calle Joralemon para niños