Joseph Glanvill facts for kids

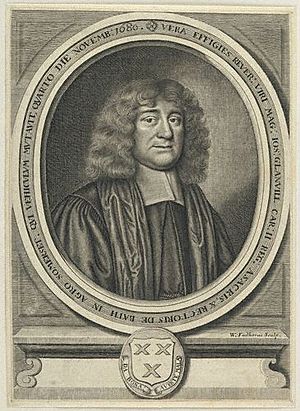

Joseph Glanvill FRS (born 1636 – died 4 November 1680) was an English writer, thinker, and church leader. He wasn't a scientist himself. However, he was known as a top supporter of the English natural philosophers of his time. These were people who studied nature and the world around them. In 1661, he even predicted that talking to people far away, like in India, might become as normal as writing letters.

Contents

Joseph Glanvill's Life

Joseph Glanvill grew up in a very strict Puritan family. He went to Oxford University. He earned his first degree from Exeter College in 1655. Later, he got his master's degree from Lincoln College in 1658.

In 1662, Glanvill became the vicar (a type of church leader) in Frome. Two years later, in 1664, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. This was a very important group for scientists and thinkers. From 1666 to 1680, he was the rector (another church leader) at the Abbey Church in Bath. In 1678, he also became a prebendary in Worcester.

His Ideas and Writings

Glanvill was a Latitudinarian thinker. This means he was part of a group that tried to find a middle way in religious and philosophical ideas. They respected the Cambridge Platonists, another group of thinkers. Glanvill was good friends with Henry More, a leader of the Platonists, and was very influenced by him. Glanvill often looked for a "middle way" in the big debates of his time. His writings show many different beliefs that might seem to disagree with each other.

Clear Thinking and Simple Language

Glanvill wrote a book called The Vanity of Dogmatizing. It was first published in 1661. This book criticized old-fashioned ways of thinking and religious unfairness. It asked for religious tolerance, the scientific method, and freedom of thought. The book also included a story that later inspired a famous poem.

At first, Glanvill followed the ideas of René Descartes. But he later changed his views a bit. He explored scepticism (doubting things) and suggested changes in his book Scepsis Scientifica (1665). This book was a new, bigger version of The Vanity of Dogmatizing. It started with a special message to the Royal Society. Because of this, the Society made him a Fellow. He continued to speak for his kind of careful doubt and for the Royal Society's goal of creating useful knowledge.

Glanvill believed in using simple, clear language. He thought words should be defined well and not rely too much on metaphors. In his Essay Concerning Preaching (1678), he also argued for simple speech in sermons. He thought preachers should be clear, not just blunt.

In another book, Essays on Several Important Subjects in Philosophy and Religion (1676), he wrote an important essay. It was called The Agreement of Reason and Religion. In it, he argued that reason and being a dissenter (someone who disagreed with the official church) didn't go together. He also attacked religious ideas that relied on imagination rather than reason. Glanvill believed that the world couldn't be understood by reason alone. Even supernatural events, he thought, needed to be studied carefully, like a science experiment. Because of this, he tried to investigate supposed supernatural events by talking to people and looking at where they happened.

Investigating the Supernatural

Glanvill is also well known for his book Saducismus Triumphatus (1681). This book was published after he died by Henry More. It was a bigger version of his earlier work, A Blow at Modern Sadducism (1668). The book argued against people who doubted the existence and power of witchcraft. It included many stories from the 1600s about witches. It even had one of the first descriptions of a witch bottle. Glanvill wanted to show that witchcraft was real.

The book became a collection of writings from different authors. It grew from his Philosophical Considerations Touching the Being of Witches and Witchcraft (1666). This earlier book was written to Robert Hunt. Hunt was a judge who was very active against witches in Somerset, where Glanvill lived. The 1668 version, A Blow at Modern Sadducism, argued that legal processes like Hunt's court should be trusted. To argue against them, Glanvill thought, would weaken society's laws.

Glanvill's interest in witchcraft might have started at a party in 1665. Other guests included Henry More and other thinkers. Glanvill and More had already talked about a famous case of poltergeist activity, known as the Drummer of Tedworth, in 1663.

Saducismus Triumphatus greatly influenced Cotton Mather's Wonders of the Invisible World (1693). Mather wrote his book to explain the Salem witch trials that happened the next year. Glanvill's book was also criticized by Francis Hutchinson in his An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (1718). Both books talked a lot about reports from Sweden. Sweden had experienced a panic about witchcraft after 1668.

Historian Jonathan Israel wrote that people like Robert Boyle, Henry More, and Joseph Glanvill fought to keep people believing in spirits. They did this to support religion, authority, and old traditions. These thinkers believed that the growing doubt about witchcraft could be stopped by careful research. Like More, Glanvill thought that the Bible clearly showed spirits existed. He believed that denying spirits and demons was the first step towards atheism (not believing in God). Atheism, he thought, led to rebellion and social problems. So, it had to be stopped by science and the work of educated people.

Saducismus Triumphatus was also translated into German in 1701. This German edition was used by Peter Goldschmidt in his similar book in 1705. This brought Glanvill's book to the attention of Christian Thomasius. Thomasius was a philosopher and law professor who doubted witchcraft. For over 20 years, Thomasius published translations of books by English doubters. He added strong introductions that attacked Glanvill and others who believed in witchcraft.

Debates on Atheism and Doubt

Even with his views, Glanvill himself was sometimes accused of not believing in God. This happened after he argued with Robert Crosse. They debated whether the ideas of Aristotle, an ancient Greek thinker, were still valuable. In defending himself and the Royal Society, Glanvill criticized how medicine was taught. In return, he was attacked by Henry Stubbe.

Glanvill's views on Aristotle also led to an attack by Thomas White, a Catholic priest. In a book from 1671, Glanvill clearly explained the "philosophy of the virtuosi" (the Royal Society's approach). He said that "plain objects of sense" should be trusted. He also said that people should "suspend assent" (wait to agree) until there was enough proof. He claimed this approach was against both doubt and being too quick to believe. He denied being a sceptic. Today, some think his approach was a type of rational fideism. This means using reason to support faith.

His book Philosophia Pia (1671) was directly about the link between the Royal Society's "experimental philosophy" (science based on experiments) and religion. It was a reply to a letter from Meric Casaubon, who criticized the Society. Glanvill used it to question the origins of "enthusiasm," which was a main target among nonconformists. He also dealt with criticisms from Richard Baxter, who also accused the Society of leaning towards atheism.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |