Lê Duẩn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lê Duẩn

|

|

|---|---|

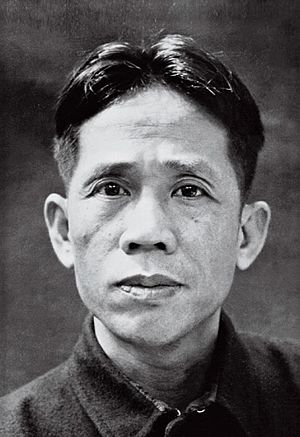

Official portrait, 1978

|

|

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam | |

| In office 10 September 1960 – 10 July 1986 |

|

| Preceded by | Hồ Chí Minh (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Trường Chinh |

| Secretary of the Central Military Commission of the Communist Party | |

| In office 1977–1984 |

|

| Preceded by | Võ Nguyên Giáp |

| Succeeded by | Văn Tiến Dũng |

| Member of the Politburo | |

| In office 1957 – 10 July 1986 |

|

| Member of the Secretariat | |

| In office 1956 – 10 July 1986 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Lê Văn Nhuận

7 April 1907 Quảng Trị Province, French Indochina |

| Died | 10 July 1986 (aged 79) Hanoi, Vietnam |

| Resting place | Mai Dich Cemetery |

| Nationality | Vietnamese |

| Political party | |

| Children | 7 (including Lê Vũ Anh) |

| Signature | |

Lê Duẩn (born Lê Văn Nhuận; April 7, 1907 – July 10, 1986) was a very important Vietnamese communist leader. He became the top leader of the Communist Party of Vietnam (VCP) in 1960. He continued the ideas of Hồ Chí Minh, who was the previous leader. From the mid-1960s until his death in 1986, Lê Duẩn was the main decision-maker in Vietnam.

He grew up in a poor family in Quảng Trị Province, which was then part of French Indochina. He learned about revolutionary ideas in the 1920s while working as a railway clerk. Lê Duẩn helped start the Indochina Communist Party in 1930. He was put in jail twice by the French, first in 1931 and again in 1939. He was freed after the August Revolution in 1945, when the Communists took power.

During the First Indochina War (1946-1954), Lê Duẩn was a key revolutionary leader in South Vietnam. He pushed for Vietnam to be reunited, even if it meant war. By 1960, he was officially the second most powerful person in the Party, after Hồ Chí Minh. As Hồ's health got worse, Lê Duẩn took on more responsibilities. After Hồ died in 1969, Lê Duẩn became the most powerful leader in North Vietnam.

He led North Vietnam throughout the Vietnam War (1955-1975). He believed that attacking was the best way to win. After South Vietnam and North Vietnam reunited in 1976, Lê Duẩn became the General Secretary of the Party for the whole country. He was very hopeful about Vietnam's future. However, his economic plans did not work well, and Vietnam faced a big economic crisis. He also supported Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia in 1978. This led to a war with China in 1979 and made Vietnam become closer to the Soviet Union. Lê Duẩn remained the General Secretary until he died in 1986.

Early Life and Political Start

Lê Duẩn was born on April 7, 1907, in a small village in Quảng Trị Province. His family was poor, and his parents worked with metal. He got a French colonial education and then worked for the railway company in Hanoi in the 1920s. There, he met communist activists and learned about Marxism.

In 1928, Lê Duẩn joined the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League. He helped create the Indochina Communist Party in 1930. He was arrested and jailed in 1931, but was released six years later. From 1937 to 1939, he rose higher in the Party. He was jailed again in 1939 for trying to start an uprising. He was freed in 1945 after the August Revolution, when the Indochinese Communist Party took power. After his release, he became a trusted helper of Hồ Chí Minh.

During the First Indochina War, Lê Duẩn was a key leader in South Vietnam. He led the Central Office of South Vietnam from 1951 to 1954. In 1953, he moved to North Vietnam.

The "Road to the South" Plan

After the 1954 Geneva Accords divided Vietnam into North and South, Lê Duẩn helped reorganize the fighters in the South. In 1956, he wrote a paper called The Road to the South. In this paper, he called for a revolution to reunite Vietnam. His ideas became the main plan for the Party in 1956, though it took until 1959 to fully start.

In 1956, Lê Duẩn joined the Party's secretariat. He was told to lead the revolutionary fight in South Vietnam. He traveled there and told the southern communists to stop fighting in the name of religious groups. He also became the acting head of the Communist Party in late 1956. In 1957, he became a member of the powerful Politburo.

By 1958, Lê Duẩn was second only to Hồ Chí Minh in the Party. He visited South Vietnam secretly in 1958 and wrote a report saying that North Vietnam needed to help the southern fighters more. The Party decided to start the revolution in January 1959.

Becoming First Secretary

Hồ Chí Minh chose Lê Duẩn to be the First Secretary of the Party in 1959. He was officially elected to this role at the 3rd National Congress. He was seen as a good choice because he had been in prison and strongly believed in reuniting Vietnam.

Leading as General Secretary

Power and Leadership

Lê Duẩn officially became the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam in 1960. This meant he took over as the Party's main leader, even though Hồ Chí Minh was still the chairman. Hồ still had influence, and Lê Duẩn often had dinner with him and other important leaders. As Hồ's health declined in 1964, Lê Duẩn took on more daily decision-making.

After Hồ Chí Minh died on September 2, 1969, Lê Duẩn became the most powerful figure. The Party leaders promised to continue working together as a group. Lê Duẩn led Hồ's funeral and gave the final speech.

The Party leadership had different groups: some favored the Soviet Union, some favored China, and some were more moderate. After the war, Lê Duẩn, who favored the Soviet Union, worked with others to remove leaders who favored China. Lê Duẩn used his position as General Secretary to gain more power. He controlled who got important jobs in many government departments.

To make their power stronger, Lê Duẩn and his allies helped their friends and family get important jobs. For example, Lê Duẩn's friend, Đồng Sĩ Nguyên, became Minister of Transport. However, most of these people did not reach the very top levels of Vietnamese politics.

The Vietnam War

At the 3rd National Congress, Lê Duẩn called for a group to be formed in South Vietnam to fight for the people. This group, called the Viet Cong, was created on December 20, 1960. Lê Duẩn said the Viet Cong would bring together "all patriotic forces" to overthrow the South Vietnamese government and reunite the country peacefully.

After the split between China and the Soviet Union, Vietnam's leaders were divided. From 1956 to 1963, Lê Duẩn tried to be neutral. But after the death of South Vietnamese President Ngô Đình Diệm and the Gulf of Tonkin incident, he became more aggressive. Unlike Hồ Chí Minh, who wanted a peaceful solution, Lê Duẩn wanted "final victory" through military action.

When the United States military became more involved in 1965, North Vietnam's military plans had to change. Lê Duẩn believed the war would become "fiercer and longer." He still thought the South Vietnamese government was weak. He wanted the North Vietnamese army to keep attacking in small ways to wear down the enemy. He also believed that the US would not attack North Vietnam directly.

In 1967, Lê Duẩn and his group decided on a big plan called the General Offensive/General Uprising. This plan involved attacks across South Vietnam, hoping to cause a popular uprising and force the US to leave. This plan was launched during the Tết holiday in January/February 1968. The Tet Offensive was a military loss for North Vietnam, but it was a strategic success because it changed public opinion in the US. After this, the North Vietnamese army was told not to risk all their forces in one big attack again.

By July 1974, with US aid to South Vietnam cut off, North Vietnam decided to invade in 1975 instead of 1976. They believed an earlier victory would make Vietnam stronger against China and the Soviet Union. After the victory, Lê Duẩn said that the Communist Party was the only leader of the Vietnamese people's struggle. In 1976, the country was reunited as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Lê Duẩn's government imprisoned many South Vietnamese who had fought against the North. This led to a large number of people leaving Vietnam, known as the Vietnamese boat people.

Economic Challenges

After the war, Vietnam's economy was in bad shape. Industry was almost non-existent, and the country's farms were badly damaged. Many people were refugees, injured, or unemployed.

In 1975, Lê Duẩn was very optimistic. He promised that every family would have a radio, refrigerator, and TV within ten years. He thought he could easily combine the consumer society of the South with the farming society of the North. In 1976, the Party said Vietnam would become fully socialist in twenty years. However, this optimism was wrong, and Vietnam faced many economic problems.

People's income went down, and malnutrition increased. The government even asked for help from the United Nations. Lê Duẩn's policies and the wars with Cambodia and China made living standards worse.

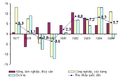

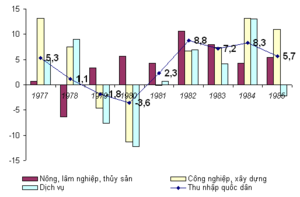

The main goals of the Second Five-Year Plan (1976–80) were to improve farming, develop light industry, and complete the socialist transformation in the South. Vietnam hoped to get help from the Soviet Union and other countries. However, the plan to make farms socialist failed badly. Many socialist farms in the South collapsed by 1980. This led to a sharp drop in food production in 1977 and 1978.

Lê Duẩn focused on heavy industry, but this did not help the economy. From 1979 to 1980, industrial production fell. The Party realized that the government controlled too much.

By 1979, Lê Duẩn admitted that mistakes had been made in economic policy. The Party started to discuss the roles of government planning and the market. They also allowed families and private businesses to have a bigger role. Lê Duẩn supported these changes in 1982. He talked about needing to strengthen both the central planned economy and the local economy. He admitted that the Second Five-Year Plan had failed.

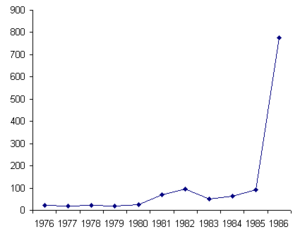

These changes did not have a big effect at first. From 1981 to 1984, farm production grew, but the government did not increase important supplies like fertilizer. By the end of Lê Duẩn's rule in 1985–1986, inflation was very high, making economic policy difficult.

Foreign Relations

With the Soviet Union

Lê Duẩn visited the Soviet Union in October 1975. The Soviets promised to send experts to Vietnam and give economic help. This cooperation was part of a larger plan for socialist countries to work together. Vietnam joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) in 1978, which was a group of socialist countries.

In 1978, Lê Duẩn and Phạm Văn Đồng signed a 25-year friendship treaty with the Soviet Union. With Soviet support, Vietnam invaded Cambodia. In response, China invaded Vietnam. Vietnam then allowed the Soviet Union to use some of its military bases. Vietnam became a strong ally of the Soviet Union in Asia.

At the 5th National Congress, Lê Duẩn said that working with the Soviet Union was the "cornerstone" of Vietnam's foreign policy. He said their alliance guaranteed Vietnam's defense and socialist development.

With China

During the Vietnam War, China claimed that the Soviet Union would betray North Vietnam. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai told Lê Duẩn that the Soviets would lie to improve relations with the United States. Lê Duẩn did not agree and called the Soviet Union a "second motherland." Because of this, China started to cut its aid to North Vietnam.

Relations got worse when China and the US started to become friends. North Vietnam felt betrayed because they were still fighting the Americans. North Vietnamese leaders believed that US President Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972 was "against the interests of Vietnam." The North Vietnamese started to hide information from China about their military plans.

Chinese and Vietnamese documents show that relations got worse from 1973 to 1975. Vietnam claimed China hindered reunification, while China claimed the problem was Vietnam's policy towards certain islands. The main issue for China was to reduce Vietnam's cooperation with the Soviets.

During Lê Duẩn's visit to China in June 1973, Zhou Enlai told him that North Vietnam should follow the peace agreements. China opposed immediate reunification and started making economic deals with the South Vietnamese Communist government. This further damaged relations.

Lê Duẩn visited China again in September 1975 to ask for aid. He tried to assure China that Vietnam wanted good relations with both China and the Soviet Union. However, no agreement for free aid was made, and Lê Duẩn left earlier than planned. Relations with China continued to get worse.

Lê Duẩn visited China again in November 1977 to seek aid. Chinese Chairman Hua Guofeng said relations had worsened because they had different ideas. Hua said China could not help Vietnam due to its own economic problems. Lê Duẩn argued that the only difference was how they viewed the Soviet Union and the United States. After his visit, China stopped all economic projects with Vietnam.

Chinese Invasion of Vietnam

On February 17, 1979, the Chinese army crossed into Vietnam. They withdrew on March 5 after a two-week fight that damaged northern Vietnam. Both sides suffered many losses. Peace talks failed, and both countries built up their forces along the border. There was fighting on the border throughout the 1980s.

Vietnamese Invasion of Cambodia

The Communist Party in Cambodia (KCP) was weaker than the Vietnamese and Laotian parties. When Vietnam started sending military aid to the Khmer Rouge in 1970, the Khmer leaders were still unsure. Vietnamese troops entered Cambodia, and Vietnamese officials thought the Khmer Rouge leaders were becoming "afraid."

After Pol Pot took control of the KCP in 1973, relations between Cambodia and Vietnam got much worse. Vietnamese troops in Cambodia were often attacked by their Khmer Rouge allies. By 1976, even though relations seemed normal, both sides were suspicious. Vietnamese leaders hoped that pro-Vietnamese people would rise within the KCP. When Cambodian radio announced Pol Pot's resignation, Lê Duẩn thought it was true. He told the Soviet ambassador that Pol Pot had been removed. He believed that another Cambodian leader, Nuon Chea, was "our man and is my personal friend."

On April 30, 1977, Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge) attacked several Vietnamese villages. The Vietnamese leaders were shocked and counterattacked. Vietnam still wanted better relations. Lê Duẩn described the Cambodian leaders as "strongly nationalistic and under strong influence of Peking [China]." He mistakenly believed that Nuon Chea had pro-Vietnamese views.

On December 31, 1977, Cambodia broke off relations with Vietnam. They said Vietnamese forces had to leave to "restore the friendly atmosphere." The real problem was Vietnam's plan to create a Vietnamese-led Indochinese Federation. Vietnamese troops left Cambodia in January, taking many prisoners and refugees. The Cambodian leaders saw this as a big victory. Cambodia did not respond to diplomatic efforts and launched another attack. Vietnam responded by encouraging an uprising against Pol Pot and then invaded.

On December 25, 1978, Vietnam sent 13 army divisions into Cambodia. Cambodia tried to fight back in a traditional way, but lost half its army in two weeks. On January 7, 1979, the Vietnamese army entered Phnom Penh, Cambodia's capital. The next day, a pro-Vietnamese government, called the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), was set up. The fighting between the Khmer Rouge and the PRK continued until Vietnam left Cambodia in 1989.

Final Years and Death

By the time of the 5th National Congress, the Party leadership was very old. The five most powerful leaders were all over 70. Lê Duẩn was 74 and was believed to be in poor health. He had traveled to the Soviet Union many times for medical treatment. He looked weak and old when he read his report to the Congress.

At the 5th National Congress, Lê Duẩn and his allies gained a lot of power. They put their supporters in important positions. Several moderate leaders and those who favored China were removed from the Politburo. General Võ Nguyên Giáp, a famous military leader, was also forced to leave the Politburo. In their place, Lê Duẩn appointed military men.

Lê Duẩn's report to the 5th National Congress was a strong self-criticism of his leadership and the Party's management. He criticized corruption and the fact that the leaders were so old. The Central Committee had only one member under 60. During this time, there was fighting within the Central Committee between those who wanted reforms and those who wanted to keep things the same. This struggle eventually led to economic reforms.

Lê Duẩn reportedly had a heart attack after the Congress and was hospitalized in the Soviet Union. He remained General Secretary until he died of natural causes in Hanoi on July 10, 1986, at age 79. He was temporarily replaced by Trường Chinh, who was then replaced by Nguyễn Văn Linh later that year.

He was buried at Mai Dich Cemetery.

Personal Life

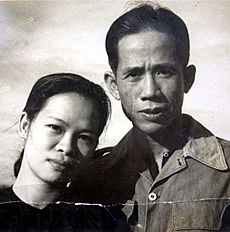

In 1929, Lê Duẩn married Lê Thị Sương. They had four children: three daughters (Lê Tuyết Hồng, Lê Thị Cừ, Lê Thị Muội) and one son (Lê Hãn).

In 1950, Lê Duẩn married Nguyễn Thụy Nga, who was of Chinese background. They had three children: one daughter (Lê Vũ Anh) and two sons (Lê Kiên Thành, Lê Kiên Trung).

Political Ideas

Lê Duẩn was a strong nationalist. During the war, he said that the "nation and socialism were one." He believed it was important to build socialism in politics, economy, and culture, and to defend the socialist homeland. He was often called a pragmatist, meaning he focused on practical results. He sometimes changed traditional Marxism–Leninism ideas to fit Vietnam's unique situation, especially in farming. Lê Duẩn believed in a strong, central government control over the economy.

He talked about "the right of collective mastery," meaning people should have control. However, in practice, he sometimes went against this. For example, he criticized Party members who asked for higher prices for farmers' products. His idea of collective mastery was that the state would manage things to ensure people's right to be "collective masters."

Lê Duẩn's idea of "collective mastery" was included in the 1980 Vietnamese Constitution. It said that people's collective mastery in all areas was guaranteed by the state. This meant people could participate in government and mass organizations.

Lê Duẩn believed that land ownership involved a "struggle" between collective farming and private farming. He thought that collective ownership was the only way to avoid capitalism. So, it was introduced without much argument by the country's leaders.

By the late 1970s, allowing peasants to work on farms under contract became common and was made legal in 1981. Some saw this as a temporary break from strict socialist development, like Lenin's New Economic Policy. Others saw it as a new way to bring socialism to farming.

Lê Duẩn sometimes went against traditional Marxist–Leninist ideas for practical reasons. He said Vietnam had to "carry out agricultural cooperation immediately, even before having built large industry." He admitted this was unusual but insisted Vietnam was in a unique situation. He believed that the key to socialism was not just machines and factories, but a new way of organizing work. He also thought that cooperative farms needed to be connected to other cooperatives and to the state-controlled economy. He saw the economy as one whole system directed by the state.

In his speech after the 1976 parliamentary election, Lê Duẩn talked about making socialism perfect in the North by removing private ownership. In the South, he wanted to get rid of the "comprador bourgeoisie" (business people who profited from dealing with Westerners) and the last "remnants of the feudal landlord classes." He also planned to remove the entire business class in the South.

Honours and Awards

Vietnam:

Vietnam:

Cuba:

Cuba:

Czechoslovakia:

Czechoslovakia:

Laos:

Laos:

Soviet Union:

Soviet Union:

Order of Lenin (1982)

Order of Lenin (1982) Lenin Peace Prize

Lenin Peace Prize

A square in Moscow, Russia, was named in his honor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Lê Duẩn para niños

In Spanish: Lê Duẩn para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |