La Junta Indians facts for kids

The La Junta Indians were a group of Native American peoples. They lived where the Rio Grande and the Conchos River meet. This area is called La Junta de los Rios, which means "the joining of the rivers." It is located on the border of West Texas and Mexico today.

In 1535, a Spanish explorer named Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca visited these people. The La Junta Indians grew crops in the rich soil near the rivers. They also gathered wild plants and caught fish. Their home was a busy trading spot, so many different tribes came through the area.

Over time, the Spanish set up missions in the 1700s. The Native Americans slowly lost their tribal identities. Many people died from diseases, the Spanish slave trade, and attacks from Apache and Comanche tribes. Because of this, the La Junta Indians eventually disappeared. Some married Spanish soldiers, and their families became part of the Mestizo population in Mexico. Others joined the Apache and Comanche. Some also went to work on Spanish farms or in silver mines.

Contents

The La Junta Region

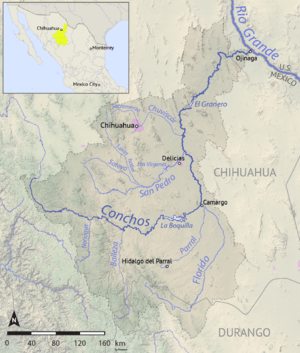

The Rio Grande and the Conchos River join together near the modern cities of Presidio, Texas, and Ojinaga, Mexico. The Conchos River is actually bigger than the Rio Grande. But after they meet, the river is still called the Rio Grande. Spanish explorers named the area La Junta because it was where the rivers joined.

A wide, flat area stretches along the Rio Grande for about 35 miles upstream and 18 miles downstream. It also goes up the Rio Conchos for 30 miles. This flat area is called a floodplain. It has many reeds, mesquite bushes, willows, and cottonwood trees.

Two higher areas, called terraces, rise above the floodplain. Only desert plants grow on these terraces. The La Junta Indians lived on these higher terraces. They used the floodplain below for farming, fishing, hunting, and gathering wild foods. Tall mountains surround the river valley and terraces.

La Junta is in the middle of the Chihuahua Desert. It gets about 10.8 inches (270 mm) of rain each year. Long dry periods are common. Summers are very hot, and winters are mild, but it does freeze often.

Ancient History of La Junta

Plenty of water, plants, and animals drew indigenous peoples to La Junta for thousands of years. People began living in settled villages and farming around 1200 A.D. This farming added to their traditional hunting and gathering.

Archaeologists think that people from the Jornada Mogollon culture settled La Junta. These people lived near modern-day El Paso, Texas, about 200 miles up the Rio Grande. La Junta may also have been influenced by Casas Grandes. This was a famous ancient Indian civilization from the late 1300s, located 200 miles west in Mexico. Its people built large communities with multi-story buildings. They used advanced irrigation systems to help their crops grow.

Recent studies of house styles and burial customs suggest that the La Junta people might have been native to the area. Between 1450 and 1500, many Jornada Mogollon villages in western Texas were left empty. This might have been due to a drought that made farming too hard. The people living there might have gone back to hunting and gathering. This way of life leaves fewer signs for archaeologists to find.

The villages at La Junta seemed to survive the drought. But the types of houses changed, and unique pottery made locally became more common. The styles of their houses and burial practices were different from the Mogollon. Most of the old pottery found at La Junta was Jornada Mogollon. But archaeologists believe it was traded for, not made there. La Junta eventually made its own special pottery style, perhaps around 1500 A.D. The La Junta people, though influenced by the Mogollon, might have been a different language and ethnic group.

Research on bones and teeth shows that the La Junta people still relied on hunting and gathering. This was true even after they settled down and started farming. Researchers were surprised to learn that less than 25 percent of their food came from corn. The rest came from hunted animals and wild plants. This is different from most farming cultures, where cultivated crops provide most of the food.

We know little about their language or languages. Scholars do not agree on what language the La Junta people spoke. The most common guess is that they spoke Uto-Aztecan. But Kiowa–Tanoan and Athapaskan (like Apache) have also been suggested. Since the La Junta people lived at a crossroads in the desert, they might have been different groups who spoke many languages. For example, the nomadic Jumano people often visited and traded. They might have also lived there part-time. They were known to be different from the full-time villagers.

Because there was not much land for farming and the environment was harsh, scholars guess that 3,000 or 4,000 people lived at La Junta. But the Spanish explorer Antonio de Espejo thought there were more than 10,000 people. Some modern experts agree that enough resources were there to support such a population. However, others disagree. The population likely changed throughout the year, as many Indians were semi-nomadic. The Spanish called the different groups at La Junta by names like Amotomancos, Otomoacos, Abriaches, Julimes, and Patarabueyes. Sometimes, they were all called Jumano. But that name might be better for the nomadic buffalo hunters who also visited La Junta often.

Spanish Explorers Arrive

The Spanish explorer Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca likely passed through or near La Junta in 1535. He was on his way to a Spanish settlement. He reported meeting "the people of the cows." He said they were "people with the best bodies that we saw and the greatest liveliness." These were probably the Jumano, who hunted buffalo further north and east. They traded and spent winters in the La Junta region. Cabeza de Vaca said the area had many people and farms, but not much good land. The Indians had not planted corn for two years because of a dry spell. Cabeza De Vaca noted that they used hot stones in gourds to cook their food. He did not say they used pottery. Like other nomadic people, they found pottery too heavy to carry easily. The Indians did not get horses from the Spanish until the 1600s.

In the 1580s, two small Spanish groups visited La Junta. These were the Chamuscado and Rodriguez expedition and later Antonio de Espejo's group. They reported that the men were "handsome" and the women "beautiful." The Indians lived in low, flat-roofed houses. They grew corn, squash, and beans. They also hunted and fished along the river. They gave the Spanish well-prepared deer and buffalo skins. The explorers' descriptions of La Junta showed a more settled farming people than what Cabeza de Vaca had described 50 years earlier.

They wrote that the houses at La Junta looked like:

those of the Mexicans ... The natives built them square. They put up forked posts and in those they place rounded timbers the thickness of a man's thigh. Then they add stakes and plaster them with mud. Close to the houses they have granaries built of willow ... where they keep their provisions and harvest of mesquite and other things.

This type of house is called a jacal. The floors of these houses were usually dug about 18 inches below ground. This helped protect against very hot or cold temperatures. Their towns were built on terraces above the river. Each town had about 600 people.

The people grew crops on the floodplains below their towns. They planted in areas made wet by river overflows or small streams. Farming in these conditions was risky. So, the people also gathered wild foods like mesquite, prickly pears, and agaves. They caught catfish in the rivers. Some La Junta Indians traveled to the Great Plains, 150 miles or more northeast. There, they hunted buffalo or traded for buffalo meat with the nomadic Jumano.

The Spanish found the Rio Grande Valley well-populated north to modern-day El Paso, Texas. Beyond that, they did not meet any people until the Pueblo villages. These were fifteen days' travel upriver from El Paso. Above La Junta, they met people later called the Suma and Manso Indians. These groups seemed to farm less and move around more than the people of La Junta.

Based on their weapons and shields, fighting between the La Junta Indians and their neighbors seemed common. Spanish explorers described bows made stronger with buffalo tendons. They also saw "excellent shields" made of buffalo hide. Spanish slave raids at La Junta might have started as early as 1563. Around the same time, Apache Indians began raiding from the north. The Spanish took captured La Junta Indians to work in the silver mines of Parral, Chihuahua.

Later Years of La Junta

After the Spanish found faster ways to travel north to their colonies in New Mexico, they stopped going through La Junta. The area became quiet, only visited by slavers and priests. In the 1600s, the population dropped. This was due to diseases from Europe, and raids by Apache and Spanish groups.

In 1683, a Jumano man named Juan Sabeata made the Spanish interested in La Junta again. He asked the governor in El Paso to send priests to the area. He said the Indians wanted to become Christian. Sabeata also asked the Spanish to help La Junta defend against the Apache. Four priests and several soldiers were sent to La Junta. When they arrived, the Indians had already built churches with thatched roofs for them. The Spanish made Sabeata a governor. La Junta became an important trade center for a short time. But Sabeata could not get Spanish help to fight the Apache.

In 1689, Indians across northern Mexico rebelled against the ongoing slave trade. The missions in La Junta were then closed. The Spanish tried to return there. A group visited in 1715 and found the population had fallen to 2,100 people. They did not build a fort and mission until 1760. By this time, the number of La Junta Indians had dropped even more. Many survivors soon left the area. They were discouraged by the harsh Spanish rule, continued Apache raids, and a new threat from the Comanche. The Comanche had moved south from Colorado. Some La Junta Indians were forced to work in the silver mines of Parral. Others married Spanish soldiers, and their families became part of the Mestizo population. Still others joined their former enemies, the Apache and the Comanche.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |