Lilias Armstrong facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lilias Armstrong

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait, unknown date

|

|

| Born |

Lilias Eveline Armstrong

29 September 1882 Pendlebury, Lancashire, England

|

| Died | 9 December 1937 (aged 55) North Finchley, Middlesex, England

|

| Other names | Lilias Eveline Boyanus |

| Education | B.A., University of Leeds, 1906 |

| Occupation | Phonetician |

| Employer | Phonetics Department, University College, University of London |

|

Works

|

Full list |

| Spouse(s) |

Simon Boyanus

(m. 1926) |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without the correct software, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. |

Lilias Eveline Armstrong (born September 29, 1882 – died December 9, 1937) was an amazing English phonetician. A phonetician is a scientist who studies the sounds of human speech. She worked at University College London and became a "reader," which is a high-level academic position.

Armstrong is best known for her important work on how English speakers use their voice to show meaning (called intonation). She also studied the sounds and tones of the Somali and Kikuyu languages. Her book about English intonation, written with Ida C. Ward, was used for 50 years! She also wrote some of the first detailed descriptions of how tone works in Somali and Kikuyu.

Lilias grew up in Northern England. She studied French and Latin at the University of Leeds. She taught French for a while before joining the Phonetics Department at University College, which was led by Daniel Jones. Some of her most famous books and papers include A Handbook of English Intonation (1926), "The Phonetic Structure of Somali" (1934), and The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu (published after she died in 1940). She passed away in 1937 at age 55 after a stroke.

She was also an editor for the International Phonetic Association's journal, Le Maître Phonétique, for over ten years. People at the time praised her teaching skills. Daniel Jones, her boss, even said she was "one of the finest phoneticians in the world."

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life and Education

Lilias Eveline Armstrong was born on September 29, 1882, in Pendlebury, Lancashire, England. Her father, James William Armstrong, was a minister. Growing up in Northern England meant her speech had some unique Northern English sounds.

She went to the University of Leeds where she studied French and Latin. She was a "king's scholar," which means she received a special scholarship. In 1906, she earned her Bachelor of Arts degree and also trained to be a teacher.

After college, Armstrong taught French in East Ham for several years. She was very good at it and was on her way to becoming a headmistress. But in 1918, she decided to leave. While teaching, she started taking evening classes in phonetics at the University College Phonetics Department. She wanted to improve how she taught French pronunciation. She earned diplomas with distinction in French Phonetics (1917) and English Phonetics (1918).

Becoming a Phonetics Expert

Teaching at University College

Lilias Armstrong started teaching phonetics in 1917 during a summer course. Her boss, Daniel Jones, wanted her to work full-time at the University College London Phonetics Department. She started as a temporary, part-time lecturer in February 1918. By the end of 1918, she became the department's first full-time assistant.

She quickly moved up the ranks:

- In 1920, she became a lecturer.

- In 1921, she became a senior lecturer.

- In 1937, she became a "reader," a very respected academic title.

Armstrong also taught at the School of Oriental Studies sometimes. When Daniel Jones was away in 1920, Armstrong even became the acting head of the department. She helped interview and admit new students.

What She Taught

Armstrong taught classes on the sounds of French, English, Swedish, and Russian. She also taught a class with Daniel Jones on how to correct speech problems. A very important part of her teaching was "ear-training exercises." These exercises helped students learn to hear and recognize different speech sounds.

She was also a big part of the popular summer courses at University College. In these courses, she led daily ear-training sessions. Students loved her ear-training exercises, calling them "a great help" and "splendid." By 1921, she was also giving lectures on English phonetics. She even gave lectures for a "Course of Spoken English for Foreigners" in 1930.

Armstrong traveled to other countries to give lectures. In 1925, she went to Sweden to talk about English intonation. In 1927, she lectured in Finland. She also visited the Netherlands and the Soviet Union to share her knowledge.

Her Famous Students

Many of Armstrong's students became well-known scholars and linguists themselves.

- Suniti Kumar Chatterji, an Indian linguist, studied phonetics with Armstrong and Ida C. Ward from 1919 to 1921.

- John Rupert Firth, who later worked with Armstrong, took her French Phonetics course in 1923.

- J. C. Catford, a Scottish phonetician, took her French phonetics class when he was 17.

- Lorenzo Dow Turner, an American linguist, studied advanced phonetics with her in 1936–1937.

- Jean-Paul Vinay, a French Canadian linguist, earned his master's degree studying under Armstrong in 1937. He remembered her kindness and amazing ability to produce sounds.

Her Important Research

Working on Le Maître Phonétique

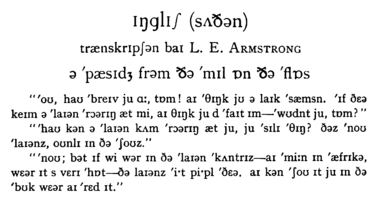

The International Phonetic Association's journal, Le Maître Phonétique, stopped publishing during World War I. But in 1921, they started a new yearly publication called Textes pour nos Élèves ("Texts for our students"). This book had texts written in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) from many languages. Armstrong wrote several English texts for it.

In 1923, Le Maître Phonétique started publishing again. Armstrong became the "subeditor" (secrétaire de rédaction) in 1923 and held this job until 1936. She played a big role in getting the journal and the International Phonetic Association active again. She wrote many book reviews and phonetic transcriptions of English texts for the journal.

She also wrote "specimens" for the journal. These were short descriptions of less-studied languages, along with a text transcribed in IPA. She wrote specimens for Swedish (1927) and Russian (1929). She even helped with a book on the pronunciation of Russian.

London Phonetic Readers Series

Armstrong wrote two books for the London Phonetics Readers Series: An English Phonetic Reader (1923) and A Burmese Phonetic Reader (1925, with Pe Maung Tin). These books helped people learn the sounds of different languages.

Her English Phonetic Reader included passages from famous writers, all written in a very detailed phonetic way. This book, along with others, helped make a new system for writing English sounds popular. Her English Phonetic Reader was printed many times, with the last one in 1956.

Her second book in the series was a Burmese reader, written with a Burmese scholar named Pe Maung Tin. They created the first system to write Burmese sounds using the International Phonetic Association's rules. This system was very detailed and used special marks to show the different tones in Burmese.

Some people thought her Burmese transcription system used too many special symbols. But Pe Maung Tin explained that these marks were needed to show how tones and speech rhythm worked together. He said it helped English speakers avoid reading Burmese texts with English intonation. An expert from the Indian Civil Service praised the book, saying it set a high standard for books on other Asian languages.

Understanding English Intonation

In 1926, Armstrong and her colleague Ida C. Ward published their famous book, Handbook of English Intonation. The book even came with three records of Armstrong and Ward reading English passages! These recordings were used for speech and theater training for many years.

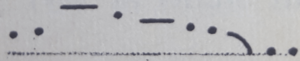

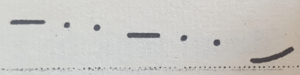

Armstrong and Ward said that all English intonation patterns could be simplified into just two "Tunes":

- Tune 1: Usually ends with a falling pitch.

- Tune 2: Usually ends with a rising pitch.

This idea was very helpful for people learning English. They showed intonation using lines and dots, where the height of the dot or line showed the pitch. This system was easy for learners to follow.

Handbook of English Intonation was very popular and used for decades, especially for teaching English. It was still being printed and used in the 1970s! While some experts later said it was a bit too simple, Armstrong and Ward knew this. They wrote the book to focus on the most common intonation patterns for foreign learners.

French Sounds and Intonation

In 1932, Armstrong wrote The Phonetics of French: A Practical Handbook. This book was made to help English students and teachers learn French pronunciation. It had many practice exercises and teaching tips. She even included her famous ear-training exercises for French teachers. This book was very well-received. In 1998, a Scottish phonetician said it was still the "best practical introduction to French phonetics."

Her main work on French intonation was the 1934 book Studies in French Intonation, written with Hélène Coustenoble. This was the first complete description of French intonation. They also analyzed French intonation using "tunes," finding three main patterns: rise-falling, falling, and rising. The book also explained how French intonation is different from English. It was called "an excellent teaching manual" and is still considered a "classic work on French intonation."

Researching Somali Language

Armstrong started studying the Somali in 1931. Her main work on Somali was "The Phonetic Structure of Somali," published in 1934. She worked with two Somali men, Mr. Isman Dubet and Mr. Haji Farah, who were sailors living in London.

Armstrong's research was very important. She was the first to carefully study tone or pitch in Somali. She said Somali had four tones: high, mid, low, and falling. She even listed pairs of words that sounded the same except for their tone. Her work influenced how the modern Somali Latin alphabet was created.

Experts praised her work. In 1981, an American phonologist called her paper "pioneering." In 1992, a linguist from Trinity College, Dublin said it was "even now the outstanding study of Somali phonetics." She was also the first to describe the vowel system of Somali and how vowels change based on other sounds (called vowel harmony).

Studying Kikuyu Language

Armstrong also wrote a short description of Kikuyu phonetics for a book on African languages. Her main work on Kikuyu was The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu, published in 1940 after her death. Jomo Kenyatta, who later became the first president of Kenya, was her language helper for this book. He worked with her from 1935 to 1937.

The book was almost finished when Armstrong died. Daniel Jones asked Beatrice Honikman to complete the last chapter and prepare the book for publication. The book included an appendix where Armstrong suggested a way to write Kikuyu using an alphabet. She tried to avoid "tiresome" special marks that people often left out when writing.

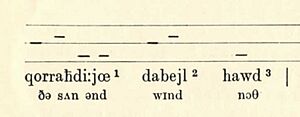

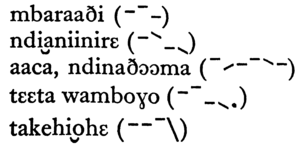

Armstrong's book was the first detailed description of tone in any East African Bantu language. She showed tone using a system of dashes at different heights, which helped illustrate the pitch changes. She grouped Kikuyu words into "tone classes" based on how their tones changed in different situations.

While some later linguists found her analysis a bit complex, her book was highly praised. A South African linguist called it "a model of meticulous investigation and recording." In 1984, an American phonologist described it as "an extremely valuable source of information due to the comprehensiveness of its coverage and accuracy of the author's phonetic observations."

Personal Life

Lilias Armstrong married Simon Charles Boyanus on September 24, 1926. He was a professor of English language studies at the University of Leningrad in Russia. He came to University College in 1925 to learn English phonetics from Armstrong. Even after getting married, she continued to use "Miss Armstrong" professionally.

After they married, Boyanus had to go back to the Soviet Union for eight years, while Armstrong stayed in England. During this time, he worked on English–Russian and Russian–English dictionaries. Armstrong helped with the phonetic spellings for the English–Russian dictionary. She visited him in Leningrad twice, and he briefly returned to London in 1928.

Finally, in January 1934, Boyanus was able to move to England permanently. He became a lecturer in Russian and Phonetics at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at the University of London. While working at University College, Armstrong lived in Forest Gate and Church End, Finchley.

Her Passing

In November 1937, Lilias Armstrong became very sick with the flu. Her condition got worse, and she had a stroke. She passed away at Finchley Memorial Hospital, Middlesex, on December 9, 1937, at the age of 55. Her funeral service was held at Golders Green Crematorium. Many important people from University College attended.

Her death was reported in many newspapers and journals, including The Times and The New York Times. Daniel Jones, her boss, was very sad about her death. He wrote her obituary for Le Maître Phonétique and honored her life in the preface to her posthumously published Kikuyu book. After World War II, when the phonetics library was rebuilt, Jones donated a copy of Armstrong's Kikuyu book to honor her memory.

Selected Works

- Armstrong, Lilias E. (1923). An English Phonetic Reader. London: University of London Press.

- Armstrong, Lilias E.; Pe Maung Tin (1925). A Burmese Phonetic Reader. London: University of London Press.

- Armstrong, Lilias E.; Ward, Ida C. (1926). Handbook of English Intonation. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner.

- Armstrong, Lilias E. (1932). The Phonetics of French: A Practical Handbook. London: G. Bell.

- Armstrong, Lilias E.; Coustenoble, Hélène (1934). Studies in French Intonation. Cambridge: W. Heffer.

- Armstrong, Lilias E. (1934). "The Phonetic Structure of Somali". Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen. 37 (3): 116–161.

- Armstrong, Lilias E. (1940). The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu. London: Oxford University Press for the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |