Lillian Moller Gilbreth facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lillian Moller Gilbreth

|

|

|---|---|

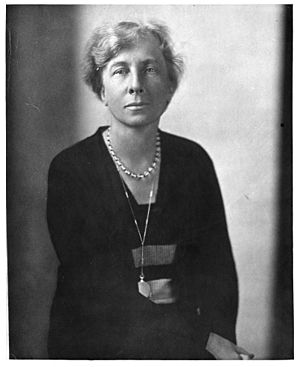

Gilbreth in 1921

|

|

| Born |

Lillie Evelyn Moller

May 24, 1878 Oakland, California, U.S.

|

| Died | January 2, 1972 (aged 93) Phoenix, Arizona, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley Brown University |

| Occupation | Industrial psychologist Ergonomics expert Management consultant Professor |

| Known for | Seminal contributions to human factors engineering and ergonomics; Therblig |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 12, including Ernestine, Frank Jr., and Robert |

| Awards | National Academy of Engineering (elected 1965) Hoover Medal (1966) |

Lillian Evelyn Gilbreth (born Moller; May 24, 1878 – January 2, 1972) was an amazing American psychologist and industrial engineer. She was a pioneer in using psychology to study how people work, especially in factories. She helped create the field of industrial/organizational psychology.

Lillian and her husband, Frank Bunker Gilbreth, were experts in making things more efficient. They studied how people moved and worked to find the "one best way" to do tasks. Their work helped create ergonomics, which is about designing tools and workspaces to fit people better.

You might know their family story from the books Cheaper by the Dozen (1948) and Belles on Their Toes (1950). Two of their twelve children wrote these books, showing how their parents used efficiency ideas even in their large family! Both books were later made into movies.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in California

Lillie Evelyn Moller was born in Oakland, California, on May 24, 1878. She was the second child and oldest of nine children who lived to adulthood. Her parents were well-off and had German roots. Lillian was homeschooled until she was nine. After that, she quickly moved through public school grades. She was a top student and graduated from Oakland High School in May 1896.

College Dreams and Challenges

Lillian really wanted to go to college. However, her father didn't think it was right for his daughters. She convinced him to let her try for one year. She got into the University of California in August 1896, but had to take an extra Latin course. The university was in Berkeley, California, and didn't charge tuition for California residents. Classes were often very large.

Lillian did very well in her first year, almost at the top of her class. This made her father agree to let her continue. She traveled from home by streetcar and helped her mother and siblings in the evenings. She studied English, philosophy, and psychology. She also earned a teaching certificate. In 1900, she became the first woman to speak at a University of California graduation ceremony.

Advanced Studies and Psychology

After college, Lillian wanted a professional career. She decided to be called Lillian, feeling it was more fitting for a university graduate. She went to Columbia University in New York City for graduate school. A big influence on her was studying with psychologist Edward Thorndike. Even after getting sick and returning home, she used his ideas in her later work.

She then returned to the University of California. In 1902, she earned her master's degree in literature. Lillian started working on her PhD at the University of California. She traveled to Europe in 1903. After marrying Frank Gilbreth and moving to New York, she finished her PhD paper in 1911. However, she didn't get the degree from California because she hadn't lived there long enough. This paper was published as The Psychology of Management in 1914.

Later, Lillian moved to Providence, Rhode Island. She enrolled at Brown University. In 1915, she earned her PhD in applied psychology. This made her the first person in industrial management to have a doctorate. Her paper was about efficient teaching methods.

Marriage and Family Life

Meeting Frank Gilbreth

Lillian Moller met Frank Bunker Gilbreth in June 1903 in Boston, Massachusetts. She was on her way to Europe with her chaperone, who happened to be Frank's cousin. Frank was a successful builder with offices in Boston, New York, and London.

They got married on October 19, 1904, in Oakland, California. They first lived in New York, then moved to Providence, Rhode Island. Eventually, they settled their family in Montclair, New Jersey.

A Large Family

Lillian and Frank had a very large family, with twelve children. One child died young, and another was stillborn. Eleven of their children lived to be adults. Their children included Ernestine Gilbreth and Frank Bunker Gilbreth Jr..

After Frank died suddenly in 1924, Lillian never remarried.

Career and Contributions

Combining Psychology and Engineering

For over 40 years, Lillian Gilbreth's career mixed psychology with engineering and management. She also used her experiences as a wife and mother in her research. She became a pioneer in what we now call industrial and organizational psychology. She helped engineers understand how important people's feelings and thoughts are at work.

Lillian and Frank ran their own business, Gilbreth, Incorporated. They wrote many books and papers together. Sometimes, Lillian wasn't listed as a co-author, perhaps because publishers worried about having a female writer. Even though she had a PhD, she was less often credited than her husband, who didn't go to college.

The Gilbreths believed that just telling people to work faster wasn't enough. They thought engineers and psychologists needed to work hard to make workplaces better for people. They helped improve the ideas of "scientific management" by focusing on the human side of work.

Time, Motion, and Fatigue Studies

Lillian and Frank were equal partners in their company. Lillian continued to lead it for decades after Frank's death in 1924. They were very good at time-and-motion studies. Their method was called the Gilbreth System, and their slogan was "The One Best Way to Do Work."

They even used motion-picture cameras to film people working. This helped them redesign machines and tasks to make them more efficient and less tiring. Their work on reducing tiredness was an early step toward ergonomics. They also suggested ideas like better lighting, regular breaks, suggestion boxes, and free books to make workplaces better for people's minds.

Improving Homes and Daily Life

After her husband passed away, Lillian kept researching, writing, and teaching. She also advised businesses. She started focusing on making housework easier, even though she didn't love doing it herself! Her children even joked that their kitchen was "inefficient."

Because it was harder for women to be accepted in engineering at the time, Lillian focused her efforts on home management. She used her scientific management ideas to find "shorter, simpler, and easier ways of doing housework." This helped women have more time for other things, like paid jobs outside the home. Her children often helped with these experiments.

Lillian was key in developing the modern kitchen layout. She helped create the "work triangle" and linear kitchen designs we still use today. In the late 1920s, she worked with Mary E. Dillon to design the Kitchen Practical. This kitchen aimed to save time and effort in meal prep. It had counters at the right height and a circular layout for easy movement.

She also helped invent the foot-pedal trash can, shelves inside refrigerator doors (like for butter and eggs), and wall-light switches. She even patented ideas like an improved electric can opener. When she worked at General Electric, she talked to over 4,000 women to figure out the best height for stoves and sinks.

Lillian also helped war veterans who had lost limbs after World War I. She continued to advise companies like Johnson & Johnson and Macy's. At Macy's, she found ways to reduce eye strain by changing lights and simplify sales records.

Helping the Government and Community

Lillian Gilbreth also volunteered and advised government groups. She was friends with President Herbert Hoover and his wife. Lou Hoover asked Lillian to join the Girl Scouts as a consultant in 1929. She was active with them for over 20 years.

During the Great Depression, President Hoover asked her to lead the "Share the Work" program to help with unemployment. During World War II, she advised on education and labor issues, especially about women in the workforce. Later, she served on committees for the Chemical Warfare Board and Civil Defense. During the Korean War, she advised on women in the armed services.

Author and Educator

Lillian loved teaching. Her PhD paper at Brown University was about applying scientific management to teaching in schools.

From 1913 to 1916, she and her husband taught free summer classes on scientific management. After Frank's death, she started a formal course on motion study in 1925. These classes taught people how to use motion study in their own organizations.

To support her large family, Lillian gave many speeches at businesses and universities like Harvard and Purdue University. In 1925, she took over her husband's role as a visiting lecturer at Purdue. In 1935, she became a professor of management there, making her the country's first female engineering professor. She retired from Purdue in 1948.

After retiring, she continued to travel and teach at other universities. In 1964, at 86 years old, she became a lecturer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1968, due to failing health, she retired from public life.

Death and Legacy

Lillian Gilbreth passed away from a stroke on January 2, 1972, in Phoenix, Arizona, at 93 years old. Her ashes were scattered at sea.

She is remembered as a pioneer in industrial engineering and management. She was called "America's first lady of engineering." She used her psychology training to improve how companies worked, making them more efficient and productive. Her research focused on "the human element in scientific management," meaning she cared about how people felt and worked. She also helped start industrial engineering programs in colleges. Her book, The Psychology of Management (1914), was one of the first to combine psychology with management ideas.

Lillian also helped women in engineering. She encouraged women to study engineering and management. Purdue University awarded its first PhD in engineering to a woman two years after Lillian retired.

Many awards are named in her honor. The National Academy of Engineering has Lillian M. Gilbreth Lectureships for young engineers. The highest award from the Institute of Industrial Engineers is the Frank and Lillian Gilbreth Industrial Engineering Award. The Society of Women Engineers gives the Lillian Moller Gilbreth Memorial Scholarship to female engineering students.

Her children, Frank Jr. and Ernestine, wrote the famous books Cheaper by the Dozen (1948) and Belles on Their Toes (1950) about their family. These books were made into movies, with Myrna Loy playing Lillian.

Awards and Honors

Lillian Gilbreth received many awards and honors:

- She received 23 honorary degrees from universities like Rutgers and Princeton.

- Her picture hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

- The Gilbreth Engineering Library at Purdue University is named after her and Frank.

- In 1921, she was the second person to become an honorary member of the American Society of Industrial Engineers.

- In 1926, she became the second female member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- In 1931, she received the first Gilbreth Medal, named after her late husband.

- In 1944, she and Frank (after his death) received the Henry Laurence Gantt Medal for their work in industrial engineering.

- In 1950, she became the first honorary member of the Society of Women Engineers.

- In 1965, she was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering.

- In 1966, she was the first woman to receive the Hoover Medal.

- In 1984, the U.S. Postal Service put her on a postage stamp.

- In 1995, Gilbreth was added to the US National Women's Hall of Fame.

Selected Published Works

- A Primer of Scientific Management (1912), with Frank B. Gilbreth

- The Psychology of Management: the Function of the Mind in Determining, Teaching and Installing Methods of Least Waste (1914)

- Motion Models (1915) with Frank B. Gilbreth

- Applied Motion Study; A collection of papers on the efficient method to industrial preparedness. (1917) with Frank B. Gilbreth

- Fatigue Study: The Elimination of Humanity's Greatest Unnecessary Waste; a First Step in Motion Study] (1916) with Frank B. Gilbreth

- Motion Study for the Handicapped (1920) with Frank B. Gilbreth

- The Quest of the One Best Way: A Sketch of the Life of Frank Bunker Gilbreth (1925)

- The Home-maker and Her Job (1927)

- Living With Our Children (1928)

- Normal Lives for the Disabled (1948), with Edna Yost

- The Foreman in Manpower Management (1947), with Alice Rice Cook

- Management in the Home: Happier Living Through Saving Time and Energy (1954), with Orpha Mae Thomas and Eleanor Clymer

- As I Remember: An Autobiography (1998), published after her death

See also

In Spanish: Lillian Moller Gilbreth para niños

In Spanish: Lillian Moller Gilbreth para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |