Llano del Rio facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Llano del Rio |

|

|---|---|

Llano del Rio ruins in late 2009

|

|

| Location | Llano, California |

| Official name: Llano del Rio Cooperative Company | |

| Reference no. | 933 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Llano del Rio was a special kind of community called a commune or "colony." It was located in what is now Llano, California, which is east of Palmdale in the Antelope Valley, Los Angeles County.

A lawyer and politician named Job Harriman started this colony. He had tried to become the mayor of Los Angeles in 1911 but didn't win. He bought the land for the colony in 1913, and it officially opened on May 1, 1914.

The Llano del Rio Colony was built at the southern edge of the Mojave Desert. It was near Highway 138, close to where 165th Street East is today. The colony used water from Big Rock Creek, a stream that flowed from the San Gabriel Mountains. They built several structures using local granite rocks and wood. These included a hotel, a meeting house, and a water storage tank. There was also a small water channel made of granite and cement. You can still see parts of these old buildings at the site today.

The colony was left empty in 1918. Llano del Rio was too far from other towns to make enough money to keep going. Also, the water supply from Big Rock Creek wasn't always reliable. About 60 families from Llano del Rio moved to New Llano, Louisiana, to start a new community there.

Contents

History of Llano del Rio

Why Llano del Rio Started

Job Harriman was a lawyer and a politician. He was the person who started the Llano del Rio cooperative colony. He had run for important political jobs before, like governor of California. He also ran for vice-president of the United States in 1900. Harriman believed that people could achieve a better society through political action.

After he lost the election for mayor of Los Angeles, California in 1911, Harriman changed his focus. He became interested in showing how people could work together. He thought that if he created a successful community where people shared everything, others would see how well it worked. He hoped this would inspire more people to believe in his ideas.

Harriman later said, "People wouldn't give up their way of life unless new ways offered better advantages." He wanted to prove that working together could be better than competing.

He asked friends in Southern California for help and money. They found a large piece of land, about 9,000-acre (3,600 ha), about 45 miles (72 km) north of Los Angeles. This land had already been partly developed by another group of people. Harriman and his friends bought the land and its water rights for a small price.

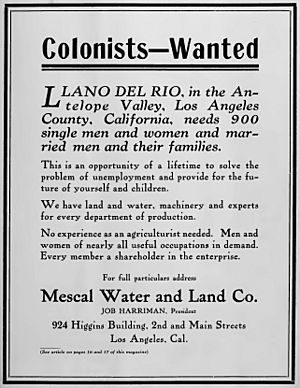

In the fall of 1913, they started selling shares to raise money for the new community. In 1914, they officially formed the Llano Del Rio Company.

Starting the Colony

To join the Llano del Rio colony, a person had to buy 2,000 shares of stock. Each share cost $1. New members also had to live at Llano. They could buy most of their shares on credit, meaning they didn't have to pay for them all at once.

People who wanted to join had to be hard-working, sober, and believe in the colony's ideals. They needed three references, usually from a local union leader. They also had to answer questions to show their dedication to the colony's goals.

One important rule was that only white people were allowed to join. A magazine called The Western Comrade tried to explain this rule. They said it wasn't about racism but because they thought it was "not deemed expedient to mix the races in these communities."

Colonists were promised good wages, $4 a day at first. Money for living expenses and stock payments was taken out of this. The rest was supposed to be paid in cash if the colony made a profit, but this never happened. So, instead of cash wages, the colony made sure all members' needs were met in exchange for their work.

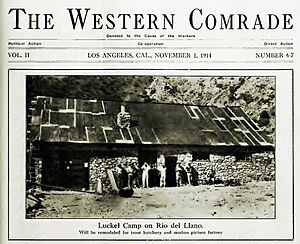

The colony's activities were shared with people across the country in The Western Comrade magazine. This magazine, bought by Job Harriman, praised the colony. It described the area as perfect for growing fruits, alfalfa, and vegetables. Two creeks provided water. However, the magazine sometimes made living at Llano sound more luxurious than it was. This led to some disappointment among new colonists.

Growing the Community

Llano opened its doors to new members on May Day in 1914. At first, only five people lived there, along with some horses, a cow, and five pigs. By early 1915, the colony had grown to over 150 residents. They also had more than 100 cows and 110 pigs.

They built a community center for dances and meetings. Unmarried men lived in a dormitory, while married couples lived in canvas tents at first. Soon, they added a post office, a dairy building, and a laundry.

A planner named Alice Constance Austin designed big plans for Llano. She imagined a circular city with administrative buildings, restaurants, schools, and markets. The houses were designed to make women's domestic work easier. They included ideas like kitchenless homes, shared childcare areas, and built-in furniture. An even bigger plan in 1917 showed row houses, a central park, and a playground. But in reality, most colonists lived in tents or small two-room shacks.

Most colonists came from the Western United States. Many were farmers or business people, but not many were wage workers. The colony often had disagreements and small political arguments. This caused some members to leave over time.

The colony had the most members in the summer of 1917, with over 1,100 people living there. By then, they had temporary adobe homes and more permanent buildings. These included a large dining hall, a hotel, and industrial buildings. They even had one of the biggest rabbit farms in the United States! They also had a printing shop for The Western Comrade magazine. They planted fruit trees and grew about 2,000 acres (810 ha) of irrigated alfalfa.

Life at Llano

How the Economy Worked

Llano's economy was mostly self-sufficient, meaning they produced almost everything they needed. They had a paint shop, farms, orchards, a poultry yard (for chickens), a rabbitry (for rabbits), a print shop, and a fish hatchery.

Even though the land was dry and sandy, Llano's farms did very well. They used the water bought by the Llano Del Rio Company to make the dry soil fertile. Southern California's warm weather was perfect for farming. Alfalfa, corn, and grain were their main crops. By 1916, Llano grew 90% of the food eaten by the colonists. However, they couldn't easily sell their farm goods outside the colony because they were far from a train station. They did sell some other items, like rag rugs and underwear, to outside markets.

Education for Kids

Llano had its own school system. It followed both the Montessori and Industrial teaching methods. These methods encourage hands-on learning and active participation, which fit well with the colony's values. In the Industrial School, also called the Kids’ Colony, children raised animals and helped build school facilities. They even made their own rules and held their own disciplinary meetings. Girls were taught "domestic science," which focused on household skills.

Fun and Free Time

May Day, a holiday celebrating workers, was a big community event at Llano. It included a parade and a picnic. Dances were held every Thursday and Saturday night. One colonist loved the dances, saying they made all the effort to join the colony worthwhile.

The colony also had a champion baseball team and other sports clubs. There was even a drama society for plays. For entertainment, they sometimes had minstrel shows. Swear words were not allowed around women or children. Alcohol was also not allowed unless a doctor gave permission. If someone broke this rule, they could lose their job or be asked to leave Llano.

Why Llano del Rio Ended

Disagreements within the Colony

Llano faced problems from disagreements among its members. The colony was run by a Board of Directors, which had seven (and later nine) members. But all the colony members were also stockholders and part of the General Assembly.

Llano's "Declaration of Principles" said everyone should have "equal ownership, equal wage, and equal social opportunities." However, the Board made all the rules, which wasn't very democratic. This caused some members to feel unhappy.

Groups like the "Brush Gang" formed to oppose the Board's strong control. Some members thought Job Harriman wasn't truly following the colony's ideals. Frank Miller, a founder of the "Brush Gang," felt Harriman acted like a "Czar" and was against members electing their leaders. Many in the "Brush Gang" also believed the colony's economic setup wasn't truly fair or socialist.

However, running things by the General Assembly also had problems. Decisions were often influenced by personal arguments, making it hard to get things done. Resolutions were debated for hours, passed, and then changed at the next meeting. A supporter of Harriman, RK Williams, wrote that new members came with "weird forms of democracy" that didn't work for a practical community. He believed central control was needed for the colony to succeed.

World War I's Impact

Llano supported the Socialist Party's belief in peace. But the threat of young men being drafted into the army during World War I was real. Llano tried to make sure its members were conscientious objectors (people who refuse to fight for moral reasons). Still, some young men from the colony were drafted. The war also created many jobs with higher wages. This caused some less committed members of Llano to leave and work in the booming wartime economy.

Water Problems

In the early days, Harriman had gotten a lot of water for the growing colony. In theory, Llano had enough water to survive and grow. But much of this water could only be reached by building a dam. Llano asked California for a permit to build a dam. However, the California Commissioner of Corporations denied their request. They said, "Your people do not seem to have the necessary amount of experience and maybe the sums of money it will involve." Even though the planners knew about the water shortage, they kept denying the problem to potential new members until May 1917.

The Move to a New Place

In November 1917, The Western Comrade magazine announced that most of the colony would move to a new location in New Llano, Louisiana. Even with the move coming, Harriman claimed Llano had grown from a "dream" to a "concrete practicality." He said it went from a few dreamers to a thousand determined doers.

However, the new colony in Louisiana never became as big or productive as the original Llano. This was likely due to cultural differences with the local Louisiana community and the Great Depression. The small group of colonists who stayed in California eventually failed due to legal issues. In 1918, Llano declared bankruptcy.

Llano's Lasting Impact

From 1967 to 2022, Llano was remembered at Twin Oaks. Twin Oaks is a modern intentional community in Virginia with about 100 members. All their buildings are named after communities that no longer exist. "Llano" was the name of one of their shared kitchens. In 2022, Twin Oaks changed the name because Llano only allowed white members, which is a racist practice.

The original site of Llano del Rio is now recognized as California Historical Landmark #933.

A socialist architect named Gregory Ain, whose parents were Russian immigrants, lived at Llano del Rio when he was a child.

The song "Llano Del Rio" by Frank Black and the Catholics is about visiting this area today. It's on their 2001 album Dog in the Sand.

California Historical Landmark Marker

The California Historical Landmark Marker NO. 933 at the site says:

- NO. 933 SITE OF LLANO DEL RIO COOPERATIVE COLONY - This was the site of the most important non-religious Utopian experiment in western American history. Its founder, Job Harriman, was Eugene Debs' running mate in the presidential election of 1900. In subsequent years, Harriman became an influential socialist leader and in 1911 was almost elected mayor of Los Angeles. At its height in 1916, the colony contained a thousand members and was a flourishing communitarian experiment dedicated to the principal of cooperation rather than competition.'

Colony Publications

- Job Harriman (ed.), The Western Comrade. Los Angeles, CA and Leesville, LA: 1913-1918.

- Vols. 1-2 | Vols. 3-4 | Vol. 5

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |