Luís Gama facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Luís Gama

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 21, 1830 |

| Died | August 24, 1882 (aged 52) |

| Monuments | Luiz Gama |

| Nationality | Brazilian |

| Other names | Afro, Getúlio, Barrabaz, Spartacus and John Brown |

| Education | Self-taught |

| Occupation | Lawyer, writer, abolitionist |

| Known for | He was able to have had freed more than 500 people from the condition of slavery. |

|

Notable work

|

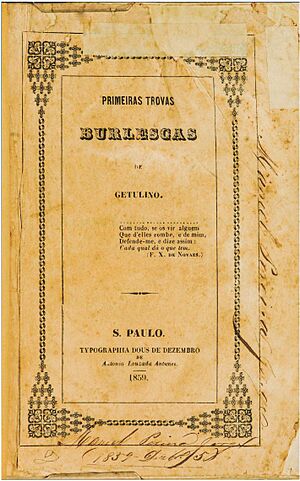

Primeiras Trovas Burlescas do Getulino |

| Political party | LP PRP (1873-1873) |

| Spouse(s) | Claudina Fortunata Sampaio |

| Children | Benedito Graco Pinto da Gama |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | XXXII Prêmio Franz de Castro Holzwarth de Direitos Humanos |

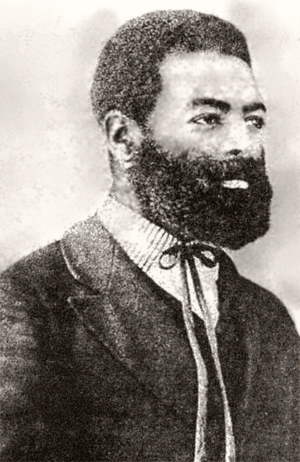

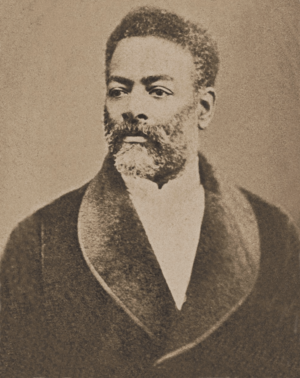

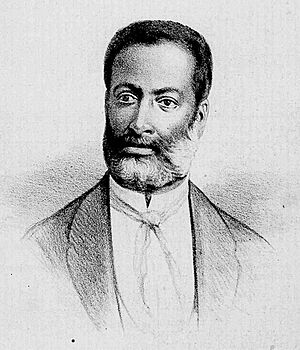

Luís Gonzaga Pinto da Gama (born June 21, 1830, in Salvador – died August 24, 1882, in São Paulo) was a Brazilian abolitionist, writer, and self-taught lawyer. He is known as the Patron of the abolition of slavery in Brazil.

Luís Gama was born to a free black mother and a white father. But he was sold into slavery at age 10. He could not read or write until he was 17 years old. He later won his own freedom in court. After that, he became a lawyer for enslaved people. By age 29, he was a famous writer. Many called him "the greatest abolitionist in Brazil."

Luís Gama was a black intellectual in 19th-century Brazil. At that time, slavery was still common. He was the only self-taught lawyer who had also been enslaved. He spent his life fighting to end slavery and the monarchy in Brazil. He died six years before these goals were achieved. In 2018, his name was added to the Steel Book of national heroes. This book honors important people in Brazil's history.

Contents

Life in Brazil during his time

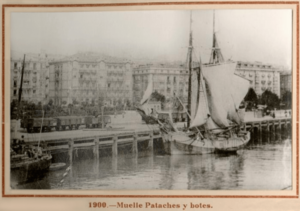

São Paulo, where Gama lived for 42 years, was a small city in the mid-1800s. By the 1870s, coffee farming grew a lot. This made the price of enslaved people very high. It became too expensive for many people in the city to own them. Before this, it was common for people to own "rent slaves." These enslaved people worked and their owners earned money from their labor. There were also "domestic slaves" who worked in homes.

São Paulo had a much smaller population than Rio de Janeiro. But it was a center for law. A law school, the Largo de São Francisco Law School, opened there in 1828. It was one of only two law schools in Brazil. Students from all over the country came to study there. They came from all social backgrounds. Gama called it "Noah's Ark in a small way."

Childhood and becoming enslaved

Luís Gama was born on June 21, 1830, in Salvador, Bahia. His mother, Luísa Mahin, was a freed African woman. His father was a Portuguese nobleman. When Luís was seven, his mother went to Rio de Janeiro. She took part in a revolt and never returned.

In 1840, when Luís was 10, his father lost money gambling. To pay his debts, he sold Luís Gama as a slave. There is no proof that his father ever looked for him again. As an adult, Gama understood that his sale was illegal. A law said it was a crime to enslave a free person. Also, after some revolts in Bahia, it was illegal to sell enslaved people from Bahia to other parts of Brazil. So, Luís Gama's sale and transport to São Paulo were against the law.

When he was offered for sale, people did not want to buy him. They said it was "for being Bahian." After a big revolt, people thought enslaved people from Bahia were rebellious. They believed they were more likely to run away. Luís was taken to Rio de Janeiro. There, he was sold to a slave trader. This trader took him to São Paulo to be resold. From the Port of Santos, Gama and other enslaved people walked to Jundiaí and Campinas. Since no one wanted to buy him, Gama worked as a house slave. He washed and ironed clothes. Later, he became a slave for hire. He worked as a seamstress and shoemaker in Lorena.

Freedom and adult life

In 1847, Luís Gama met Antônio Rodrigues do Prado Júnior. Antônio was a law student staying at Gama's master's house. He taught Gama how to read and write. By the next year, Gama was literate. He even taught his master's children to read. He used this skill to argue for his freedom, but it did not work at first.

Luís Gama eventually proved he was free. He joined the army in 1848. It is not fully clear how he got his freedom. Some think his father helped him. Others believe he ran away and used his reading and writing skills to claim he was free. He served in the City Guard until 1854. He was jailed for 39 days for "insubordination" after arguing with an officer. In 1850, he married Claudina Fortunata Sampaio.

While in the army, Gama worked as a copyist for officials. He had good handwriting. In 1856, he became a clerk at the São Paulo Police Department. He worked for Francisco Maria de Souza Furtado de Mendonça, a law professor. Gama used Mendonça's library to study law. He wanted to go to the Largo de São Francisco Law School. But students there did not want him to enroll. So, he studied on his own. He attended classes as a listener. He became a "rábula," which was a person with enough legal knowledge to be a lawyer without a degree. After helping enslaved people in court, Gama lost his job at the Police Department in 1868. This was because powerful people did not like him freeing enslaved people.

Literature and writing

Luís Gama was a reader of Vida de Jesus (Life of Jesus) by Ernest Renan. This book was published in 1863 and quickly translated in Brazil. Gama was one of the first in Brazil to mention it. His only book, Primeiras Trovas Burlescas, was published in 1859 and 1861. This made him a recognized writer just 12 years after he learned to read. The book was dedicated to Salvador Furtado de Mendonça, a judge and law professor. He likely helped Gama access his library. The book also included poems by his friend José Bonifácio the Younger. A third edition of his work was published after his death in 1904.

Poetry: "Orpheus with a curly top"

Luís Gama was called "Orpheus with a curly top." This name referred to the Greek poet Orpheus and Gama's curly hair. He was skilled at both serious and funny poetry.

His poems often spoke from his own experience. He proudly showed his black heritage. But he also used common images from his time. These included figures from mythology like Orpheus and Cupid. He also mentioned famous poets like Lamartine.

However, Gama changed these images to fit his own life. His muse (source of inspiration) was from Guinea. His Orpheus had "curly top." When he wrote about white society, he used strong satirical (mocking) images:

|

Com sabença profunda irei cantando |

With deep wisdom I will sing |

He used parts of white culture to show the opposite of black culture. He filled his poems with traditional poetry elements. For example, he compared the "Guinea muse" to the Greek and Roman muses. He used dark granite instead of white marble. He mentioned the marimba and cabaço instead of the lyre and flute:

|

Ó Musa da Guiné, cor de azeviche, |

Oh Muse of Guinea, black as jet, |

In his poems, Gama showed himself in a way that was different from how white poets described black people. He was not a "poor wretch" or a sufferer. He used strong criticism against himself, just as he criticized the system. He made fun of his own worth compared to the common cultural ideas.

|

Se queres, meu amigo, |

If you want, my friend, |

Gama even made fun of the situation of black people. They were kept away from wealth, science, and art:

|

Ciências e letras |

Science and letters |

The "Goat" poems

"Goat" (Bode) was a rude word used in Gama's time. It was used to insult black and mixed-race people. Gama himself was called this name. In 1861, in his poem Quem sou eu? (Who am I?), also known as Bodarrada (Goat Herd), Gama used the term in a funny way. He made fun of Brazilian society. At the same time, he stated that all humans are equal, no matter their skin color:

|

Se negro sou, ou sou bode, |

Whether I am black, or a goat, |

Fighting for freedom

Journalism and secret societies

Luís Gama fought for freedom through his work in newspapers. He started his journalism career in São Paulo. In 1864, he and cartoonist Angelo Agostini started the first funny newspaper in São Paulo, called Diabo Coxo (Lame Devil). It ran until 1865. Before this, he had worked at other newspapers. By 1869, his work as a journalist and lawyer made him very important in São Paulo. Gama was not rich. He gave his money to people in need. He was the only black abolitionist in Brazil who had experienced slavery himself.

Gama also wrote articles for other newspapers. He wrote about social and racial issues in Brazil. He spoke out against unfair decisions. For example, he criticized a judge who allowed an enslaved person to be auctioned off after their master died, even though the master's son had freed them. His work made him many enemies. He even received threats against his life.

In 1866, Gama, Agostini, and Américo Brasílio de Campos started another newspaper called Cabrião. All three were part of the same Masonic lodge. A Masonic lodge is like a club where members share ideals. They all believed in a republic and ending slavery. The America Masonic Lodge was very active in fighting slavery. Luís Gama helped start it. At the time of his death, Gama was a leader in this group.

One of Gama's projects in the Masonic lodge was to create a free school for children. He also wanted an evening school for adults. He was also thought to be behind a community library with 5,000 books. His writings show he believed in public and non-religious schools. He supported this idea 30 years before it was widely discussed.

The "Gama style" of law

In 1831, a law was passed in Brazil. It said that bringing enslaved people into Brazil was illegal. Any person brought in after this law should be free. This was called the Feijó Law. But it was often ignored. People called it a "law for the English to see." This meant it was passed to make Britain happy, but it wasn't really enforced. However, Luís Gama used this law to free enslaved people.

Gama's special way of practicing law was called the "Gama style." He would prove in court that enslaved black people were brought to Brazil illegally after 1831. If he could prove this, they had to be freed.

In 1871, the Lei do Ventre Livre (Free Womb Law) was passed. This law said that children born to enslaved mothers would be free. It also required slave owners to register each enslaved person they owned. If an enslaved person was not registered, Gama could use this to argue for their freedom. The law also allowed enslaved people or others to buy their freedom. Gama and other abolitionists would pretend to be slave valuers. They would lower the price of freedom, allowing more people to be freed.

Gama mostly defended black people accused of crimes or those who ran away. He also helped them gain legal freedom. But he also helped poor people of any background for free. He even defended European immigrants. Gama also helped newly freed people find jobs.

In a letter, Gama said he had freed over 500 enslaved people. In 1869, in a court case called the "Netto Question," Gama freed 217 enslaved people. The BBC called this the "largest known group action to free slaves in the Americas."

Gama once said a famous phrase in court: "The slave who kills the master, in whatever circumstance, always kills in self-defense." This caused a big reaction and the judge had to stop the session. Some historians say this exact phrase was written by a friend about Gama, not by Gama himself. But the idea that enslaved people had the right to defend themselves was often in Gama's work. For example, he defended four enslaved people who killed their master's son. Gama called them "four Spartacus" (a famous gladiator who led a slave revolt).

His views on race

Luís Gama did not like African descendants who acted like white people. He also disliked those who became cruel slave owners. He found it funny when slave owners of mixed race tried to pretend they were white. He once told a colonel who called him "Goat": "I am not a goat, I am black. My color does not deny it. A goat is your honor who intends to disguise, with this light color, the mulatto underneath." This showed his pride in his identity.

Political work

Luís Gama was part of the Liberal Party. He shared his ideas for a free Brazil without a king or slaves in a newspaper article in 1869. Later, he helped try to start a republican party. In 1873, he joined the First Republican Congress. But he found that many members of the Paulista Republican Party owned enslaved people. They did not care about ending slavery. Gama believed slavery should end right away, without paying slave owners. So, he left the party. He then criticized the party and other newspapers that claimed to support abolition but still published ads for capturing runaway slaves.

Death and funeral

The writer Raul Pompeia noticed that Gama's health was failing. On the morning of August 24, 1882, Gama lost his ability to speak. He died that afternoon from diabetes.

When Luís Gama died, Raul Pompeia was shocked. He went to Gama's house. Many people were already there, mourning. Men cried, and women sobbed. Gama's body was in a coffin in the front room. A sculptor made a plaster mold of his face. The next day, the coffin left at three in the afternoon. Just before it closed, his wife cried out. The cemetery was far away. A funeral coach was ready, but the crowd would not let it go. They wanted to carry "Everyone's friend" themselves. Shops closed, and flowers were thrown.

Friends carried the coffin. A huge crowd followed, wanting to help carry it. Many carriages followed behind, including the empty funeral coach. At four o'clock, the procession reached Brás. A band played sad music. More groups joined the funeral. Stores closed their doors, and flags flew at half-mast. People filled the streets to watch. Many cried.

Professor Otávio Torres said Luís Gama died "glorified by São Paulo." Antônio Loureiro de Sousa wrote in 1949 that his funeral was "the largest ever reported in those days." People from all walks of life were there. They all wanted to carry the coffin. Even a slave owner and a poor, barefoot black man carried it together. It was evening when they reached the cemetery. The crowd stayed. After a short sermon, the coffin was taken to the grave. Before it was lowered, someone shouted for everyone to wait. After a speech about Gama's importance, everyone cried. Then, they swore an oath to continue the fight for freedom.

His grave was bought the same day by his wife, Claudina.

What happened after his death

Gama's death and the powerful speeches at his funeral changed the abolitionist movement. Before, it focused on legal ways to free enslaved people. After Gama, it became more active. People like Clímaco Barbosa led the way. They hid runaway slaves and helped them reach safe places like the Quilombo do Jabaquara. They also encouraged large groups of enslaved people to escape from farms.

One example was when members of the Brás Abolitionist Club stormed a farm. They shouted, "Long live the abolitionists, let the slave owners die!" Many important people and ordinary citizens became police suspects for these actions.

In 1879, Luís Gama knew his health was getting worse. He started thinking about more extreme ways to fight slavery. Antônio Bento, who left his job as a judge to fight slavery, was very important in this. He became known as "the ghost of abolition." Antônio Bento took over as the lawyer for the Abolitionist Club after Gama died. Later, the Abolitionist Party and the Caifazes movement continued Gama's work. They took stronger actions to end slavery.

Honors and influence

Many people honored Luís Gama after he died. Raul Pompeia wrote an article about him called "Last page in the life of a great man." Pompeia also drew a picture of Gama for a newspaper. He even started a story called A Mão de Luís Gama (The Hand of Luís Gama).

Years after his death, a Masonic lodge called the Luís Gama Lodge was founded. It helped 25 black men join.

In 1919, a train station was named after him. Between 1923 and 1926, a newspaper called Getulino appeared. It was named after one of Luís Gama's pen names. This newspaper helped black people get more involved in society.

In São Paulo, there is a statue of him. It was put there by the black community in 1931 to honor his 100th birthday.

Over time, Gama influenced many black Brazilian movements. A literary group called Projeto Rhumor Negro said Gama's letter to Mendonça was "one of the most important historical documents of the Brazilian people."

In 2014, writer Ana Maria Gonçalves prepared a movie script about Gama's life. She noted that not enough is said about slavery compared to other historical events. In 2015, a play called "Luiz Gama — A Voice for Freedom" began.

In 2017, the University of São Paulo Law School named one of its rooms after him. In 2018, his name was added to the Steel Book of national heroes. He was also recognized as a journalist by the São Paulo Journalists Union.

In 2019, a film about Gama's life was announced. It was first called Prisioneiro da Liberdade (Prisoner of Liberty). The film, named Doutor Gama, was released in 2021. Also in 2019, a comic book called Província Negra was published. It tells a fictional adventure based on Gama's life.

In 2021, the University of São Paulo gave him an Honoris Causa doctorate. This is a special honor. He was the first black Brazilian to receive this from the university.

Title of "lawyer"

On November 3, 2015, 133 years after his death, the Order of Attorneys of Brazil in São Paulo officially gave him the title of "lawyer." He had worked as a lawyer without a formal degree. This was the first time the Order of Attorneys of Brazil had done this. The president of the Order said it was "a very fitting tribute to someone who fought so hard for freedom, equality, and respect."

His image around the world

The Black Past website, which focuses on African and African American history, has a page about Luís Gama. In March 2020, Princeton University held a workshop about how Luís Gama freed 500 enslaved people.

Complete works

Historian Bruno Rodrigues de Lima spent nine years looking for all of Luís Gama's writings. He plans to publish ten books with about 5,000 pages of Gama's complete works. Rodrigues's research shows that Gama was already seen as a lawyer in his time. The idea that he was just a "rábula" might have been created to make him seem less important.

- Luiz Gama (2021). Bruno Rodrigues de Lima. ed (in pt-br). Democracia. Obras Completas. 4 (1 ed.). Hedra. pp. 500. ISBN 9786589705123.

- Luiz Gama (2021). Bruno Rodrigues de Lima. ed (in pt-br). Liberdade. Obras Completas. 8 (1 ed.). Hedra. pp. 446. ISBN 9786589705161.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Luiz Gama para niños

In Spanish: Luiz Gama para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |