Lyttelton Rail Tunnel facts for kids

|

|

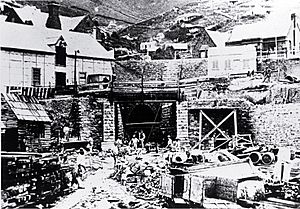

| Heathcote portal of Lyttelton railway tunnel. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | Main South Line |

| Location | Christchurch, New Zealand |

| Coordinates | 43°35′32.15″S 172°42′45.55″E / 43.5922639°S 172.7126528°E |

| Status | Open |

| Start | Lyttelton |

| End | Heathcote |

| Operation | |

| Owner | KiwiRail |

| Operator | KiwiRail |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 2.595 kilometres (1.612 mi) |

| Gauge | 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) (1863–1876) 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) (1876–present) |

| Electrified | 1500 V overhead (1929–1970) |

The Lyttelton Rail Tunnel, also known as the Moorhouse Tunnel, connects the city of Christchurch with the port of Lyttelton. Both are in the Canterbury region of New Zealand's South Island. This tunnel is New Zealand's oldest working rail tunnel. It is part of the Lyttelton Line, one of the first railways built by the Canterbury Provincial Railways.

When it opened in 1867, it was the first tunnel in the world to go through the side of an extinct volcano. At 2.7 kilometres (1.7 mi) long, it was also the longest tunnel in New Zealand at that time. Its opening meant the Ferrymead Railway, New Zealand's very first public railway, was no longer needed.

Contents

Building the Lyttelton Rail Tunnel

Why a Tunnel Was Needed

When European settlers arrived in Canterbury in 1850, they faced a big problem. They needed to move people and goods between the harbour at Lyttelton and the flat Canterbury Plains. There were only two difficult ways to do this. One was the Bridle Path over the Port Hills. The other was by ship around the coast and up the Heathcote or Avon Rivers.

Early ideas for a tunnel came up in 1849. Captain Joseph Thomas thought about it but didn't have the money or workers. In 1851, a local auctioneer, J. Tullock, asked for surveys to see how long a tunnel would be.

Later, a group of settlers looked into the best way to connect the port and the plains. They heard a tunnel could cost a lot, between £100,000 and £150,000. Some thought a tunnel was "too visionary" and too expensive. They decided to focus on improving the road first.

When the Canterbury Provincial Council was formed in 1853, they also looked at transport options. They considered two main ideas for a railway. One was a direct route through a 2.5 km tunnel to Lyttelton. The other was a longer route around the coast.

Because they couldn't agree on the best plan, the railway project was put on hold. This made the transport problem even worse. In 1858, the leader of the province, Superintendent William Sefton Moorhouse, pushed for the tunnel idea again. The council then set aside money to hire an engineer and find companies to build the tunnel.

Engineers like Edward Dobson and George Robert Stephenson studied the different routes. They decided the direct route through the hills to Lyttelton was the best. It was shorter, cheaper to build, and easier to maintain.

Public Support for the Tunnel

Superintendent Moorhouse strongly supported building the tunnel. In the 1857 election for provincial leader, the tunnel became the main topic. Moorhouse's opponent, Joseph Brittan, was against the idea.

Moorhouse received a lot of support from people in Lyttelton. He won the election by a large number of votes. This showed that many people wanted the tunnel built. Moorhouse officially started the project by turning the first sod (a piece of earth) on 17 July 1861.

How the Tunnel Was Built

The first contractors, John Smith and George Knight from England, agreed to finish the tunnel in five years. They sent miners to New Zealand in 1859.

However, the miners found the rock was much harder than expected. They asked for an extra £30,000 to finish the work. The Canterbury Government decided not to continue with them. It turned out Smith & Knight were having money problems.

Provincial Engineer Edward Dobson then suggested his own plan. The biggest problem was water leaking into the tunnel. Dobson proposed drilling more shafts to drain the water. Work started with 340 men.

Superintendent Moorhouse kept pushing for the railway. He went to Melbourne, Australia in 1861 to find new contractors and get a loan. He found a company called Holmes & Richardson. George Holmes agreed to build the tunnel for £188,727.

Work on the tunnel officially began on 17 July 1861. Miners worked from both ends of the tunnel. The speed of work depended on how hard the rock was.

The two ends of the tunnel finally met on 28 May 1867. Temporary rails were laid by mid-November. The first train, Locomotive No. 3, went through the tunnel on the night of 18 November. The first goods train followed a week later. Passenger services started on 9 December 1867.

The tunnel was fully completed in June 1874, after more work was done.

How the Tunnel Has Been Used

Changing the Railway Tracks

When the New Zealand government decided to have one national railway track size, they allowed some older railways to keep their original wider tracks. Canterbury's railways were one of these.

However, the provincial government decided to lay a new, narrower track next to the existing wide track. This meant both types of trains could use the line. The narrow-gauge line reached Christchurch in March 1876 and Lyttelton a month later.

Dealing with Smoke from Steam Trains

Steam locomotives produced a lot of smoke inside the tunnel, which was a problem. In 1909, the Railways Department tried converting a locomotive, WF 433, to burn oil. This reduced the smoke, but it was too expensive to do for all trains.

Electric Trains in the Tunnel

The second solution was to use electric trains. After the Otira Tunnel was successfully electrified in 1923, it was decided to electrify the Christchurch – Lyttelton line too. The tunnel was already wide enough for the overhead electric wires because it was built for larger trains.

The first electric train ran through the tunnel on 14 February 1929. Electric trains continued until 1970. By then, the EC class electric locomotives were old. Also, fewer trains were needed after the Lyttelton road tunnel opened in 1964. So, the electric system was removed, and diesel trains took over.

The Tunnel Today

Today, the Lyttelton Rail Tunnel is used only by freight trains. About six scheduled return services run daily from the port of Lyttelton through the tunnel. These include coal trains from places like Hector and Ngakawau on the West Coast. Other trains also carry different goods between the city and the port.

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |