Mark Felt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mark Felt

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 2nd Associate Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation | |

| In office May 3, 1972 – June 22, 1973 |

|

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Clyde Tolson |

| Succeeded by | James B. Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Mark Felt

August 17, 1913 Twin Falls, Idaho, U.S. |

| Died | December 18, 2008 (aged 95) Santa Rosa, California, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Audrey Isabelle Robinson

(m. 1938; died 1984) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater |

|

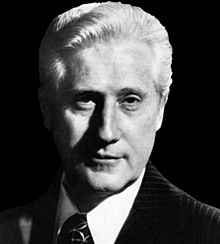

William Mark Felt Sr. (born August 17, 1913 – died December 18, 2008) was an American law enforcement officer. He worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973. Felt became famous for his secret role in the Watergate scandal.

He was an FBI special agent who rose to be the Associate Director. This was the second-highest job in the FBI. In 2005, when he was 91, Felt told Vanity Fair that he was the secret source known as "Deep Throat." He gave important information about the Watergate scandal to The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. This information eventually led to President Richard Nixon resigning in 1974.

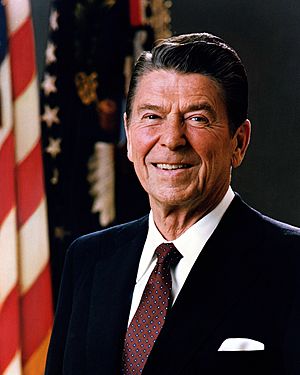

In 1980, Felt was found guilty of violating people's rights. He had ordered FBI agents to secretly enter homes of people linked to the Weather Underground group. This was part of an effort to stop bombings. He was fined, but President Ronald Reagan later gave him a pardon while Felt was appealing his case.

Felt wrote two books about his life: The FBI Pyramid in 1979 and A G-Man's Life in 2006.

Contents

Early Life and Joining the FBI

Mark Felt was born on August 17, 1913, in Twin Falls, Idaho. His father was a carpenter. Felt graduated from Twin Falls High School in 1931.

He then went to the University of Idaho and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1935. After college, Felt moved to Washington, D.C. He worked for a U.S. Senator.

In 1938, Felt married Audrey Robinson. They had two children, Joan and Mark. Audrey passed away in 1984.

Felt also studied law at night at George Washington University Law School. He earned his law degree in 1940. He was allowed to practice law in 1941.

He applied to the FBI in November 1941 and started working there on January 26, 1942.

Early Years at the FBI

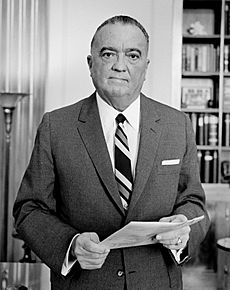

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover often moved agents to different offices. This helped them gain wide experience. Felt completed 16 weeks of training. He then worked in FBI offices in Houston and San Antonio.

He returned to FBI Headquarters in Washington. There, he worked in the Espionage Section. His job was to find spies and saboteurs during World War II. He helped trick German agents by feeding them false information about Allied plans.

After the war, Felt worked in the Seattle office. He became a supervisor there. He oversaw background checks for workers at the Hanford Site plutonium plant. In 1954, he became an Assistant Special Agent-in-Charge in New Orleans and later in Los Angeles.

Rising Through the Ranks

In September 1962, Felt returned to Washington, D.C. He helped oversee the FBI Academy. In November 1964, he became an Assistant Director. He was the Chief Inspector and head of the Inspection Division. This division made sure FBI rules were followed and investigated problems within the Bureau.

On July 1, 1971, Director Hoover promoted Felt to Deputy Associate Director. He helped Associate Director Clyde Tolson, who was in poor health. Felt's job was to help manage the FBI's operations.

Investigations into the Weather Underground

In the early 1970s, the FBI investigated groups like the Weather Underground. This group had planted bombs in important government buildings. Mark Felt was involved in these investigations.

Later, a court dismissed a case against the Weather Underground. The court found that the FBI had done illegal things. These included unauthorized wiretaps and secret entries into homes.

After Hoover's Death

FBI Director Hoover died on May 2, 1972. The next day, President Nixon chose L. Patrick Gray to be the Acting FBI Director. Felt became the Associate Director, the second-in-command.

On the day Hoover died, his secretary started destroying his old files. These files contained private information Hoover had collected. Felt stored some of these files in his office. Gray told the public that there were no "secret files."

Felt later said that losing some papers was "no serious problem." Gray, the new director, lived far away and traveled often. This meant Felt was often in charge of the FBI's daily work.

Watergate Scandal

As Associate Director, Felt saw all the information gathered about the Watergate scandal. This information came to him before it went to Director Gray. From June 1972 until the FBI investigation ended in June 1973, Felt was a key person for FBI information.

Reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein wrote many stories about Watergate. Other FBI agents noticed that the reporters' stories often used information almost exactly from their FBI reports. This showed that someone high up in the FBI was leaking information. That person was Mark Felt, also known as "Deep Throat."

Trial and Pardon

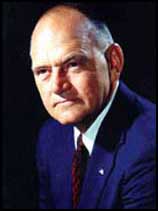

In the early 1970s, Felt oversaw some FBI operations. These operations sometimes involved secretly entering homes without a search warrant. These were called "black bag jobs." Felt and another agent, Edward S. Miller, ordered these secret entries in 1972 and 1973. They did this at homes of people connected to the Weather Underground.

Later, these actions were found to be against the law. In 1976, Felt publicly said he had ordered the entries. He believed they were justified to protect the country. He said he would "do it again tomorrow."

In 1978, a grand jury charged Felt, Miller, and Gray with violating people's constitutional rights. Felt said he was "shocked" because he believed he was acting in the country's best interest.

The trial for Felt and Miller began in September 1980. Former President Nixon even testified for the defense. He said that secret entries for national security were common. Many other former officials also said that such searches were not seen as illegal at the time.

On November 6, 1980, the jury found Felt and Miller guilty. They were fined, but not sent to prison. Felt and Miller appealed their verdicts.

On March 26, 1981, President Ronald Reagan pardoned Felt and Miller. This meant their convictions were forgiven. Nixon sent them champagne, saying "Justice ultimately prevails."

The prosecutor in the case, John W. Nields Jr., said the White House did not talk to the prosecutors before giving the pardons. Despite the pardons, Felt and Miller tried to remove the convictions from their records. Felt's law license was restored in 1982.

Family

Mark Felt married Audrey Robinson in 1938. They had two children, Joan and Mark. Audrey passed away on July 20, 1984.

His daughter Joan has three sons: Will, Robbie, and Nick.

Memoir

Felt published his book, The FBI Pyramid: From the Inside, in 1979. It shared his experiences within the FBI.

Watergate Role

People have different opinions about Felt's actions in Watergate. His family called him an "American hero." They believed he leaked information for good reasons. Others thought he might have been seeking revenge on Nixon. Many believe he acted out of loyalty to the FBI itself.

Death

Mark Felt died peacefully in his sleep on December 18, 2008. He was 95 years old. His death was due to heart failure.

See also

In Spanish: W. Mark Felt para niños

In Spanish: W. Mark Felt para niños