Michael IX Palaiologos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Michael IX Palaiologos |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

A 15th-century painting of Michael IX.

|

|||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 21 May 1294 – 12 October 1320 |

||||

| Coronation | 21 May 1294, Hagia Sophia | ||||

| Predecessor | Andronikos II (alone) | ||||

| Successor | Andronikos II (alone) Andronikos III (in Macedonia) |

||||

| Co-emperor | Andronikos II | ||||

| Proclamation | 1281 (as co-emperor) | ||||

| Born | 17 April 1277 Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) |

||||

| Died | 12 October 1320 (aged 43) Thessaloniki, Greece |

||||

| Spouse |

Rita of Armenia

(m. 1294) |

||||

| Issue |

|

||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Palaiologos | ||||

| Father | Andronikos II Palaiologos | ||||

| Mother | Anna of Hungary | ||||

Michael IX Palaiologos (born 17 April 1277 – died 12 October 1320) was a Byzantine Emperor. He ruled alongside his father, Andronikos II Palaiologos, from 1294 until his death. Both father and son were considered equal rulers and used the title autokrator, meaning "self-ruler."

Michael IX was known for being a good person and a helpful son to his father. He was also a brave and energetic soldier. He was willing to make personal sacrifices to help his troops. A writer named Ramon Muntaner once said that Emperor Michael was "one of the bravest knights in the world."

Even with his bravery, he faced several defeats in battles. The reasons for these losses are not fully clear. It might have been due to his skills as a commander, the poor state of the Byzantine army, or simply bad luck.

He died at the age of 43. His death was partly blamed on sadness. His younger son, Manuel Palaiologos, was accidentally killed by soldiers of his older son, Andronikos III Palaiologos.

People in the Byzantine Empire remembered Michael IX as "the most devoted lord." They also called him "a true emperor in name and deeds."

Contents

Early Life and Becoming Emperor

Michael IX was the oldest son of the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos. His mother was Anna of Hungary, the daughter of King Stephen V of Hungary. He was born on Easter Sunday, April 17, 1277. People at the time saw his birth on Easter as a special sign.

His father, Emperor Andronikos II, loved his first son very much. Michael's birth brought comfort to his father, especially after his mother, Anna, died in 1281. Michael IX had one younger brother named Constantine.

Andronikos II made Michael IX an emperor shortly before his own father, Michael VIII, died in 1282. Once Michael IX became an adult, his father confirmed his power. On May 21, 1294, Michael IX was crowned by Patriarch John XII of Constantinople at Hagia Sophia. In the years that followed, Andronikos II often sent his son to lead armies against enemies inside and outside the empire.

Military Campaigns

Battle at Magnesia (1302)

In the spring of 1302, Michael IX led his first military campaign. He was very proud of this chance to prove himself in battle. He gathered about 16,000 soldiers. This included 10,000 mercenary soldiers called Alans. However, these Alans did not fight well. They also stole from both Turkish and Greek people.

Michael IX set up his camp near the fortress of Magnesia ad Sipylum in Asia Minor. The Turks had taken strong positions on nearby mountains and in forests. Michael IX did not dare to attack first because his army's morale was low. He knew the Turks could easily defeat his soldiers.

The Turks then attacked. After this defeat, Michael IX went to Pergamum and then to Adramyttium. He spent the New Year of 1303 there. By summer, he was in Cyzicus. He kept trying to gather a new army. But by then, the Turks had already taken control of the Sakarya River area. They also defeated another Greek army near Nicomedia in July 1302. It became clear that the Byzantines were losing the war.

Michael IX became very sick. He reached the Pegai fortress and could not continue. He watched sadly as the Turks took over Byzantine lands. A year later, a Turkish commander captured Ephesus and briefly, the island of Rhodes.

Michael IX was sick for several months in 1303. He only got better by January 1304. He then returned to Constantinople with his wife, Rita. She had rushed to Pegai to be with him during his illness.

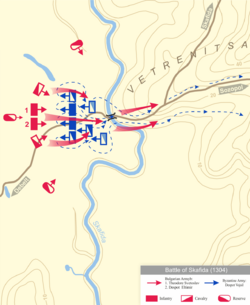

Battle of Skafida (1304)

From 1303 to 1304, Tsar Theodore Svetoslav of Bulgaria attacked Eastern Thrace. At this time, Michael IX was fighting against a group of rebellious mercenary soldiers called the Catalan Company. Their leader, Roger de Flor, refused to fight the Bulgarians unless Michael IX and his father paid him.

To stop the Catalans and Bulgarians from joining forces, Michael IX had to fight the Bulgarians. He shared command of the army with Michael Glaber. However, Glaber became very sick before the main battle. The Bulgarians had already captured many fortresses along the southern Black Sea coast.

At first, things went well for the Byzantine Empire. Michael IX won several small fights. Many fortresses that the Bulgarians had taken then surrendered to him without a fight. People in Constantinople were impressed. The Patriarch Athanasius I praised Michael IX's victories.

In the autumn of 1304, the Byzantines attacked. The two armies met near the Skafida river. Michael IX fought bravely and gained an early advantage. He made the Bulgarians retreat. But his soldiers got too excited and chased them too far.

There was a deep, fast-flowing river, the Skafida, between the Byzantines and the retreating Bulgarians. The only bridge across it had been damaged by the Bulgarians. When many Byzantine soldiers tried to cross the bridge, it collapsed. Many soldiers drowned, and the rest panicked. The Bulgarians then returned and won the battle.

Hundreds of Byzantines were captured. To get them back and raise a new army, Emperor Andronikos II and Michael IX had to sell their own jewels. The fighting continued for several more years. In 1307, a peace treaty was signed that was not good for the Byzantine Empire. As part of the deal, Michael IX had to give his daughter Theodora in marriage to the Bulgarian Tsar Theodore Svetoslav.

Battle of Apros (1305)

In the spring of 1305, Michael IX met with the rebellious Catalan mercenary leader Roger de Flor in Adrianople. Roger de Flor was very demanding. He wanted control of all of Anatolia and a huge amount of money for his soldiers.

According to some stories, Roger de Flor was killed unfairly during a night of drinking with Byzantine commanders. He was killed by a young Alan boy whose father Roger had killed earlier. It is not clear if Michael IX was responsible for the murder. However, the Catalans were furious.

About 5,000 angry Catalans, joined by 500 Turkish warriors, took over Gallipoli. They killed all the Greek citizens there. They then began to raid Thrace, stealing everything. Their leaders, Berenguer VI de Entenza and Bernat de Rocafort, declared war on the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Andronikos II tried to explain that he had not ordered de Flor's death, but the Catalans would not listen.

Michael IX gathered an army. It included soldiers from Thrace and Macedonia, Alan cavalry, and about 1,000 baptized Turks called Turcopoles. He led them to the Apros fortress.

When the battle began, the Catalans charged with a cry of "Aragon! Aragon! Saint George!" The Turcopoles and Alans suddenly left the battlefield. This surprise scared the Byzantines. Michael IX cried and begged his soldiers to stand firm. But they ran away without looking back. Only about a hundred knights stayed with the emperor. Most of the foot soldiers were badly beaten by the Catalans.

Michael IX retreated to Didymoteicho. There, his father, Andronikos II, scolded him for putting himself in such danger. Michael also faced harsh criticism from his stepmother, Empress Irene. She hated him because she wanted her own sons to inherit the empire. The victorious Catalans then plundered Thrace for two years. After that, they moved on to Macedonia and central Greece.

The situation in Asia was also bad. The Turks managed to cut off communication between Nicomedia and Nicaea in 1307.

Turkish Fortress (1314)

After the Catalans left in 1314, Thrace was attacked by the Ottoman Turks. These Turks had been with the Catalans, and now they were returning home with their stolen goods. They asked for permission to pass through Byzantine lands, which was granted. However, Andronikos II saw how much treasure they had and how few Turks there were. He decided to attack them and take their loot.

This plan failed because the Byzantine generals were too slow and obvious. The Turks found out about the plan. They quickly attacked the nearest fortress, fortified it, and got help from Asia. Then they began to plunder the country.

Michael IX had to gather an army. They took everyone they could find, including ordinary farmers who made up most of the army. They laid siege to the fortress. The Byzantines were confident because they greatly outnumbered the Turks. The Turks had only 1,300 cavalry and 800 foot soldiers. But as soon as the Turkish horsemen appeared, led by their chief Halil, the farmers suddenly ran away. Then, the rest of the Byzantine soldiers also started to scatter. When Michael IX tried to get his army in order, no one would listen to him.

The Turks captured many Byzantine nobles, the imperial treasury, and the emperor's crown. The Turkish chief Halil even put the Byzantine emperor's crown on his own head to mock Michael IX.

A young, skilled military leader named Philes Palaeologus saved the day. He asked the emperors for permission to gather his own troops. Philes, who was not strong physically but was brave, led a small group of the best fighters. Near the Xirogypsus river, he successfully defeated 1,200 Ottomans. These Ottomans were returning to the fortress with stolen goods and Greek captives. After more soldiers arrived from Genoa, Philes forced the fortress to surrender with few losses.

Why Michael IX Struggled as a Commander

Michael IX often had to lead armies made up of mercenaries from different groups like Alans, Turks, Catalans, and Serbians. Sometimes, his army was just simple farmers. This was because the Byzantine Empire's military was in a very bad state.

Emperor Andronikos II, Michael's father, was not a military man. He thought it was too expensive to keep a regular national army. He believed that a professional group of mercenaries would be cheaper. So, the Byzantine Empire's own armed forces were disbanded. Mercenaries were hired to guard the borders instead.

However, these mercenary commanders could not control their new soldiers. The soldiers were often cowardly, greedy, and rebellious. In many cases, they openly rebelled and disobeyed orders. This made it very hard for the empire to defend itself.

Michael IX always obeyed his father. But he was not the person who could fix this broken system. It was very difficult to win battles with an army of farmers and unruly mercenaries. Even a great commander would have struggled. Philes Palaeologus, the only Byzantine leader who won a major victory under Michael IX, succeeded because he refused to work with mercenaries and peasant soldiers.

Personal Life

Marriage and Children

In 1288, Michael IX was supposed to marry Catherine of Courtenay. She was the Latin Empress of Constantinople. His father hoped this marriage would reduce the threat of the Latins trying to take over the Byzantine Empire again. It was also meant to improve relations with the Pope and European kings. However, after years of talks, the marriage did not happen.

Andronikos II considered other brides for Michael IX. He sent marriage proposals to the courts of Sicily and Cyprus. At one point, it was thought Michael IX would marry Yolande of Aragon. Another offer came from the Despotate of Epirus, who suggested his daughter Thamar. But none of these plans worked out.

Finally, Andronikos II sent a group of ambassadors to Levon II, the King of Armenia. Even though the first group was captured by pirates, the Emperor sent another. This group, led by Theodore Metochites and Patriarch John XII, asked for the hand of the Armenian princess Rita.

The ambassadors returned with Princess Rita. On January 16, 1294, Michael IX and Rita were married at Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Rita was renamed Maria, as was common for foreign princesses. Both Michael and Rita were 16 years old. They had four children:

- Andronikos III Palaiologos (born 1297 – died 1341). He became emperor after taking power from his grandfather in 1328.

- Manuel Palaiologos (died 1320). He was accidentally killed by his older brother's soldiers. They thought he was a rival for a girl Andronikos III liked.

- Anna Palaiologina (died 1320). She married twice. First to Thomas I Komnenos Doukas, Despot of Epirus, in 1307. Second to Nicholas Orsini, Count Palatine of Cephalonia, in 1318.

- Theodora Palaiologina (died after 1330). She also married twice. First to Tsar Theodore Svetoslav of Bulgaria in 1308. Second to Tsar Michael Asen III of Bulgaria in 1324.

Relationship with his Stepmother

After his first wife, Anna of Hungary, died in 1281, Andronikos II married again in 1284. He chose 10-year-old Yolanda of Montferrato. She was renamed Irene when she married, as was the custom. Michael IX and his brother Constantine were only a few years younger than their new stepmother.

Irene turned out to be an ambitious and scheming woman. She had seven children with Andronikos II, though only four survived. She did not like the idea that Michael IX, her stepson, would inherit the entire empire. She wanted her own sons to be the heirs.

After one argument with her husband, Irene and her sons left Constantinople. They went to live in Thessaloniki. The conflict between Irene and Michael IX only ended when she died in 1317. Before her death, she behaved badly. She even tried to share private details of her marriage with everyone she met.

Death

In October 1319, Michael IX's father sent him to govern Thessalonica. There, he was supposed to help end the long-standing fighting between the people of Thessaly and the Pelasgians. He accepted his father's wishes. He and his wife, Rita-Maria, moved to the city. It is said that he was worried because of a prophecy that he would die in Thessalonica.

According to an old Byzantine writer, Michael IX was buried in Thessalonica, the city where he died.

Michael and the Church

Michael IX was also known for being very religious and devoted to the Church. In the last part of his life in Thessalonica, he ordered the rebuilding of the Hagios Demetrios church. This church was dedicated to Saint Demetrius, the patron saint of Thessalonica. It had been almost completely destroyed in 1185. Under Michael's guidance, the church's ceilings were repainted, the roof was fixed, and the temple columns were restored.

Over the years, he issued many special church decrees called chrysobulls (meaning "golden seals"). His most important chrysobulls were for the Iviron (1310) and Hilandar (1305) monasteries. These monasteries had been robbed by the Catalans after the defeat at Apros. He also issued one for the Brontochion Monastery (1318). These documents freed the monks from many duties and taxes. This included not having to provide food and drinks to the state. In the chrysobull for Iviron Monastery, Michael IX described his role as "Patron saint of subjects in the interests of the common good." This meant he saw himself as a protector of his people.

See also

In Spanish: Miguel IX Paleólogo para niños

In Spanish: Miguel IX Paleólogo para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |