Military brat (U.S. subculture) facts for kids

In the United States, a military brat is a child whose parent or parents serve full-time in the U.S. Armed Forces. This term can also describe the special way of life these families experience.

Being a military brat often means moving to new states or countries many times while growing up. Because of this, many military brats don't have one specific "hometown." They also often deal with stress when a parent is deployed for war. Other unique parts of their life include living in foreign countries or different parts of the U.S., learning about new languages and cultures, and being deeply involved in military life.

The military brat way of life has been around for over 200 years. Even though it's one of America's oldest groups, it's also one of the least known. Some people even call military brats "modern nomads" because they move so much.

Within the U.S. military culture, "military brat" is a term of respect and affection. It shows that someone has experienced a lot by moving around. Many current and former military brats like the term. However, outside the military, the word "brat" can sometimes be misunderstood, as it usually means a spoiled child.

Contents

Life as a Military Kid

Growing up as a military brat is shaped by many things. A big one is moving often, as families follow their military parent(s) from one military base to another. These moves are usually very far, sometimes thousands of miles.

Other important parts of this life include:

- Becoming very strong and able to adapt.

- Often saying goodbye to friends.

- Becoming good at making new friends quickly.

- Not having one permanent hometown.

- Learning about many foreign cultures and languages when living overseas.

- Experiencing different American cultures when living in various U.S. regions.

Military kids also grow up on military bases, which are like small towns. They are surrounded by military culture. They often deal with a parent being away for deployments, the worry of a parent getting hurt in war, and the challenges of living with parents who return from war. Sometimes, military families also have a more structured home life, similar to military rules. They often learn about honor and service and see many patriotic symbols. They also get free medical care through Tricare until they are 23 or 25.

While some non-military families might have similar experiences, these things happen much more often and are more intense for military families. Military communities are close-knit and see these experiences as normal. Studies show that growing up in military culture can have lasting effects, both good and sometimes challenging.

Life on a Military Base

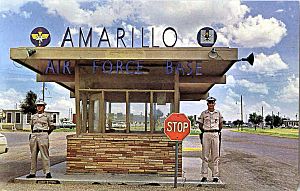

Military bases are often like small cities, with thousands of people. They are self-contained worlds where military culture is the main way of life. Military families don't always live on base, but many do. Towns near bases are also often heavily influenced by military culture. In the U.S. military, Air Force and Navy places are called "bases," while Army places are called "posts."

Military brats move from base to base as their parents get new assignments. Whether they live on or off base, the base is often the center of their lives. It has shopping, fun activities, schools, and a military community. These bases become a series of temporary homes for military kids as they grow up.

Studies show that the culture on military bases feels very different from civilian culture to most military brats. Bases have military rules, security forces, armed guards, and high-security areas. Some bases have unique features, like air bases with many noisy aircraft or seaports with lots of naval ships. But bases also have relaxed areas for housing, shopping, dining, and fun. Military rules and social codes are always in effect, which can be very different from local civilian laws.

Military language also has its own slang and acronyms. Many words and phrases are unique to the military world. For example, time is often told using a 24-hour clock instead of 12-hour. Distances are sometimes measured in meters or kilometers ("clicks") instead of yards or miles. Because of this, many military brats feel a strong military identity and a sense of being different from civilian culture, even in the United States.

Bases create communities, but because people move so often (sometimes 100% turnover in a few years), adult military brats can't easily go back to find old friends or teachers. Base schools often have even higher turnover rates. Also, once military kids turn 18 (or 23 if they are in college), they often lose their base access, making it hard to visit places where they grew up.

How Many Military Brats Are There?

The U.S. Department of Defense estimates that about 15 million Americans are current or former military brats. This includes people of all ages, from babies to over 90 years old, because military brats have existed for many generations. Many spent their entire childhood in this lifestyle, while others only spent part of it. Not all military brats move all the time, but many do.

What Studies Show About Military Kids

Experts have studied military brats a lot, looking at their social and psychological development and their unique culture. These studies show how this lifestyle tends to affect them, on average. Individual experiences can vary greatly.

Good Things About Being a Military Kid

Studies show many positive traits among military brats:

- They are often very strong and resilient.

- They have excellent social skills.

- They have a high level of understanding about different cultures and the world.

- Many are good at foreign languages.

- They often choose careers that involve helping others, like military service, teaching, counseling, police work, nursing, or foreign service.

- Some choose independent or creative jobs.

- They tend to do well if they join the military themselves.

As adults, military brats share many traits with other people who moved a lot as children. They have a wide range of experiences from living around the world. They often connect more with other mobile kids than with those who stayed in one place. Military brats also graduate from college at a higher rate and divorce at a lower rate than the general civilian population.

Challenges for Military Kids

On the other hand, studies show some challenges:

- Some former military brats find it hard to form deep, lasting friendships.

- They can feel like outsiders in U.S. civilian culture.

- The constant moving can make it hard to build strong connections with people or places.

- They deal with the stress of a parent being deployed to a war zone.

- They may face the psychological effects of war when a parent returns.

- Sometimes, a parent is lost in combat, or changes drastically due to a war-related injury.

- A military brat might know other kids whose parents were hurt or killed in war.

- A small number of former military brats may show signs of PTSD or other anxiety issues.

Always Wanting to Move?

Many adult military brats say they find it hard to settle down in one place and often want to move every few years. They sometimes call this "the itch." However, some military brats feel the opposite and refuse to move again.

Perfectionism and Adapting

Many former military brats say they have struggled with perfectionism at some point, perhaps because of the demanding nature of military culture. Yet, most of these same people describe themselves as successful, showing their ability to overcome or manage these challenges.

Most military brats say they developed a special ability to adapt and fit into new situations quickly, just as they did with each move to a new base or country. However, many also feel like outsiders when it comes to civilian (non-military) culture. For example, one study found that 32% of military brats feel like they are just watching U.S. life, and 48% don't feel like they truly belong to any group.

Military Culture and Values

Many military brats find it hard to form strong connections with people or places. But they often form strong bonds with (or sometimes dislike) the idea of a military base and its community. This is because military life has its own set of values, ideas, and ways of doing things that can be different from civilian culture. Military bases are like small, self-contained towns that encourage people to fit in. Families often shop at the same stores, and everyone might have similar clothes or products.

Values and Patriotism

Patriotism means different things to different former military brats, but it is a strong part of how many of them grew up. The comfort or strictness found on military bases comes from the consistent rituals. When moving around the world, these rituals help brats feel at home. Even if the people and places change, the "base" feels familiar because the rituals are often the same. These rituals aim to promote patriotism.

It is often said that life on military bases is linked to stronger patriotic feelings. For example, honoring the American flag is expected. At the end of the workday, on a military base, the bugle call "To the Color" plays as the flag is lowered. Everyone outside is expected to stop and stand still. Uniformed people salute, and non-uniformed people place their hand over their heart.

Until recently, the Pledge of Allegiance was recited every morning in Department of Defense schools. Patriotic songs might also have been sung. Before movies at base theaters, people stand for the National Anthem and often another patriotic song.

Military families know that a service person might be killed in duty. But they often accept this risk because they understand the values of duty, honor, and country. The military child shares in this mission through their military parent.

Military law requires leaders to show virtue, honor, patriotism, and obedience. The Army has "The 7 Army Values," summarized by the acronym "LDRSHIP": Loyalty, Duty, Respect, Selfless Service, Honor, Integrity, and Personal Courage. Military brats are raised in a culture that stresses these values. Children of military personnel often reflect their parents' values more than civilian children.

Discipline

The typical military family might have a "duty roster" on the fridge, and parents might inspect rooms. Children might say "yes sir/ma'am" to adults. Many military brats from the Cold War era described their fathers as "authoritarian," meaning they wanted to control their children's lives. They saw their military parent as strict, not flexible, and not accepting of different behaviors or emotions.

Discipline goes beyond the family. Military family members know their actions can directly affect the service member's career. If a military brat gets into trouble, authorities might call the parent's commanding officer or the base commander. This behavior could become part of the military member's record and affect their promotions or assignments.

Studies show that military brats are generally better behaved than civilian kids. This might be because military parents have less tolerance for misbehavior. Also, because teenagers move so much, they might try harder to fit in and avoid drawing attention to themselves. They also know their behavior is watched and can affect their parent's career.

Teenage years are usually a time for becoming independent and taking risks. But when a teenager lives in a small, self-contained community like a base, challenging rules can be harder. Military brats know that misbehavior will likely be reported to their parents. They are often pressured to act maturely. If they grow up overseas or on bases, they might have fewer chances to see many different types of role models.

Sometimes, strict discipline can have the opposite effect, causing brats to rebel or develop psychological problems from the constant stress of always having to be on their best behavior.

Military Class Differences

Military life is strictly divided by rank. The facilities for officers and enlisted personnel are very different. Officers' housing is usually closer to base activities, larger, and has better landscaping. On bigger bases, senior officers might have even larger, fancier homes.

Officer Clubs are more elegant than Enlisted Clubs. Officers have nicer recreational facilities. Historically, base chapels and movie theaters had special seating for officers and their families. For a time, some bases even had separate Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops for officer children and enlisted children.

These differences are a core part of military life. Children of enlisted personnel sometimes feel that officer children get special treatment. The physical separation and different activities make it hard for them to mix. However, most military brats don't let this affect their friendships, and it's generally frowned upon to treat others differently based on their parent's rank.

The separation by rank helps maintain military discipline. It can be against military law for an officer to become too friendly with an enlisted person, as it could weaken the military structure. This is often taught to military children. If two brats whose parents have a boss-employee relationship become too close, it can cause problems for both parents.

To a lesser degree, military class differences also include the branch of service (Army, Navy, Air Force, etc.) a parent belongs to. Military brats will almost always say their parent's branch is the best. These biases often last into adulthood. However, as adults, military brats often share a common identity based on being a military brat, which can overcome these differences.

While there are differences in housing, military classism is different from traditional class structures in some ways. For example, all military children attend the same base schools, regardless of rank. This creates peer groups that are usually not based on class, and everyone has equal access to education. Also, all military personnel receive the same quality of healthcare.

Anti-Racism in the Military

In 1948, nearly 20 years before the civil rights movement in civilian society, President Harry S. Truman signed an order to end segregation in the military. It made it illegal to make a racist remark. In 1963, the Secretary of Defense ordered commanders to oppose discrimination against their service members and families. While these rules didn't completely stop racism, they shaped the culture in which military children grew up.

When families go overseas, minority students rarely face open racism from their neighbors. This is also true on U.S. military bases. The diverse military base community is often isolated from the off-base community. Military dependents usually see the military community as their main community, and the bonds within it are often stronger than racial differences.

Growing Up Military

Friendships and Moving

Because military brats are always making new friends to replace the ones they've lost, they are often more outgoing and independent. However, always being the "new kid" can make them feel like a stranger everywhere, even if they settle down later in life. A large study found that 80% of military brats say they can relate to anyone, no matter their race, background, religion, or nationality.

A typical military school can have up to 50% of its students change every year. Social groups constantly form and break apart. Military kids learn to adapt quickly to these changing environments. Children who move a lot are more likely to reach out to a new student because they know what it feels like to be new.

Recent studies show that even though brats move every 3 years on average, they don't necessarily get used to it. The constant change and openness to others can have a cost. Instead of solving problems, there's a temptation to just leave a problem behind when you move. However, when military brats marry, it's often for life; over two-thirds of brats over 40 are still married to their first spouse. While many become very adaptable, a small number may experience anxiety or difficulty forming close attachments.

School Life

Moving during the summer can be tough. Classes taken at an old school might not count for graduation at a new one. Moving during winter holidays or mid-year has traditionally been seen as the worst time. Students have to join classes that have already started. Social groups are harder to join, and activities might be closed. For example, an athlete might miss tryouts. However, recent studies suggest that moving during the school year might be less stressful than summer moves.

Department of Defense schools overseas (DoDDS) and in the U.S. (DDESS) are often smaller than many public schools. Students and teachers often have a closer relationship. When military kids return to civilian schools, the lack of this closeness with teachers can be a surprise.

Military brats tend to have lower rates of delinquency, higher scores on standardized tests, and higher average IQs than their civilian peers. They are more likely to have a college degree (60% vs. 24%) and an advanced degree (29.1% vs. 5%). U.S. military brats are the most mobile of "third culture kids," moving every three years on average and often spending years abroad.

International Experiences

Sociologist Morten Ender studied military brats whose parents served from their birth through high school. His study found that 97% lived in at least one foreign country, 63% in two, and 31% in three. They moved an average of eight times before high school and spent about seven years in foreign countries. Over 80% now speak at least one language other than English, and 14% speak three or more. Growing up in a mobile community offers experiences not usually available to families who stay in one place.

Military Kids Today

In 2010, the U.S. Defense Department reported that 2 million American children and teenagers had at least one parent deployed to war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan. Over 900,000 had a parent deployed multiple times.

Most research on military brats has focused on adults who grew up during the Cold War, Vietnam, and Korean wars. After the Cold War, the U.S. military changed living standards to improve quality of life. The military also changed, with more married members. Since there's less base housing, more families live off-base.

Today, more civilians fill important military roles, and large "megabases" combine different service branches. The U.S. has also been involved in long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The long-term effects of these changes are still being studied, but there is research on the short-term effects on modern military brats.

War in the 21st Century

Today's military brats face new challenges. About 50,000 military families have both parents serving, meaning both could be deployed at the same time. Also, communication is much faster now with the Internet. Families can talk to service members in combat zones, which keeps them closer. But it also increases tension because more details reach families quickly. News channels spread news faster than the military can confirm it, so families might hear about deaths before official word arrives. This can cause a lot of fear until they know their loved one is safe.

Despite this, studies show only a small increase in immediate stress for military brats whose parents are in combat zones. Boys and younger children show the most risk, but rarely need special help. However, family life is more disrupted when a military member is deployed to a combat zone compared to a non-combat zone.

Military members can be deployed for days, months, or even years. When a parent is away, children experience emotions similar to those of children whose parents are divorced. But military brats have extra worries. They don't always know where their parent is going or when (or if) they will return. Studies show three phases of deployment, each affecting the family differently:

- Before Deployment: Stress, conflict, sadness, and negative child behavior.

- During Deployment: Loneliness, anger, stress, less social support, and difficulties with childcare.

- After Deployment/Reunion: Adjusting to new roles, communication problems, and anxiety.

The U.S. military says that separation can strengthen children by making them more independent and responsible when a parent is away.

A 2009 Pentagon study found that children of combat troops show more fear, anxiety, and behavior problems. One in four parents said their children reacted poorly, and a third had academic problems. Another study found that a year after a parent returns, 30% of children showed "clinical levels of anxiety." The Pentagon study found effects strongest in children aged 5-13, while another study found issues strongest in children under 8.

"Suddenly Military" Kids (Reserve and National Guard Brats)

Families of reservists and National Guard members face unique challenges. They can feel isolated from other military families and from their hometown communities.

With more demands on the U.S. military, reservists are called to active duty more often. Their children are technically military brats, but they might not share all the experiences of traditional military brats. However, they may share many war-related issues. To help these "suddenly military" kids, groups like "Operation: Military Kids" and "Our Military Kids" were created. These programs help them understand military culture and provide financial support for activities.

National Guard families are less familiar with military culture. They are often physically separated from other military families, meaning they might get less emotional support during wartime. It can be harder for teachers and health professionals to spot problems related to war deployment unless they specifically look for them. Even if the family isn't fully immersed in military culture, individual reservist parents might still bring military influences into the home.

Losing a Parent in Combat

The specific effects of losing a parent in military operations have not been fully studied. Limited studies on children who have lost a parent show that 10-15% experience depression. A few develop "childhood traumatic grief," where they can't remember any positive memories of the parent. Military psychiatrists believe that losing a parent in war would be more traumatic than other causes of death.

Peacetime Military Deaths

Training for war and other military duties also involve dangers. Many military brats live with the risk to their parents even when there isn't an active war. Military accidents in peacetime claim lives every year at a higher rate than civilian accidents. Some jobs, like military pilots, paratroopers, and those working with weapons, have higher death rates. Such accidents are hard to hide from children in small base communities.

Month of the Military Child

The U.S. Department of Defense has named April as "Month of the Military Child." During this month each year, special programs and support activities are held. The Department of Defense also uses the term military brat in some of its research and writings about military children.

Community for Former Military Brats

As adults, military brats sometimes try to reconnect with their shared heritage.

The book Military Brats and Other Global Nomads explains why some adult military brats seek out organizations for brats. They can feel a "sense of euphoria" when they find others who share the same feelings and experiences. The book says that brats share a bond that goes beyond race, religion, and nationality. Another common reason for joining these groups is to stay connected or reconnect with old friends.

Some people feel that military children grow up in tough, strict environments with little recognition or help. Mary Edwards Wertsch writes about her experiences and those of others in her book Military Brats: Legacies of Childhood inside the Fortress. Author Pat Conroy also wrote about the difficult circumstances of growing up in his book, The Great Santini.

What's in a Name? The Term "Military Brat"

Origin of the Term

The exact origin of the term military brat is not known. Some believe it came from the British Empire, meaning "British Regiment Attached Traveler." However, acronyms like this are from the 20th century, and there's no real proof for this theory. American military brats have existed for 200 years. Military spouses and children have followed armies for thousands of years. The term Little Traveller was used as early as 1811 to describe a soldier's child who followed the army.

In a dictionary from 1755, "brat" was defined as "a child, so called in contempt" or "the offspring." Examples were found in old writings from the 1500s and 1600s.

Modern Meaning

Mary Edwards Wertsch, a military brat researcher, asked 85 former military children if they liked the term military brat. Only five (about 6%) said they didn't like it.

The term is now widely used by researchers and academics. It's no longer just slang but a recognized name for a well-studied group in U.S. culture. Sociologist Morten Ender, an expert on military brats, wrote, "It is no wonder that the label endures and is as popular as ever."

When a group takes a word that was once insulting and uses it positively, it's called "linguistic reclamation." Non-military people might find "brat" insulting if they don't understand its military context. Sociologist Karen Williams used it in her research because the participants themselves used it and felt comfortable with it.

Military culture itself has embraced the term. Admiral Dennis C. Blair, a former high-ranking officer, said, "There's a standard term for the military child: 'Brat.' While it sounds pejorative, it's actually a term of great affection." This trend is also seen among important civilians. Senator Ben Nelson wrote that while "brat" alone isn't a compliment, "military brat" is a term of endearment. Senator John Cornyn identifies himself as a military brat. Military culture has even created positive meanings for "brat," like "Born, Raised And Transferred" or "Brave, Resilient, Adaptable, and Trustworthy." Most military brats are comfortable with the term.

In late 2014, two children's book authors suggested using "CHAMPs" (Child Heroes Attached to Military Personnel) instead of "brat." However, the adult military brat community strongly rejected this idea.

Research on Military Brats

The Term "Third Culture Kid"

In the 1970s, sociologist Ruth Hill Useem created the term "third culture kids" (TCKs). This describes a child who moves with their parents "into another culture." Useem used "third culture kids" because TCKs combine parts of their birth culture (first culture) and the new culture (second culture) to create a unique "third culture." Globally, children from military families make up about 30% of all TCKs, and most of them are from the United States.

Start of Military Research

Serious research on military children began in the 1980s. The U.S. Armed Forces supported studies on the long-term effects of growing up as a military dependent. Outside the U.S., there isn't much research on this topic. Since the Department of Defense doesn't track former military brats, studies on adults rely on people identifying themselves as brats.

Mary Edwards Wertsch: Identifying Military Brat Culture

In 1991, Mary Edwards Wertsch started the movement for military brat cultural identity with her book Military Brats: Legacies of Childhood inside the Fortress. For her book, Wertsch interviewed over 80 children of military families and found common themes. While her book wasn't a scientific study, later research has confirmed many of her findings. In the book's introduction, author and former military brat Pat Conroy wrote that Wertsch's book showed him a "secret family" he didn't know he had, with its own customs and ways of communicating.

Brats: Our Journey Home

In 2005, military brat and filmmaker Donna Musil released Brats: Our Journey Home, the first documentary about military brats. It has won six film awards. Musil argues that military brats form a distinct American subculture with a shared identity. The documentary includes interviews with researchers, counselors, psychologists, and many former military brats.

Feeling Invisible

Musil's documentary also highlights how many military brats feel that their culture and lives are largely invisible to most Americans. While some small parts of military brat life might be known, most Americans don't fully understand this large (and old) American subculture. The documentary begins with country singer and military brat Kris Kristofferson calling military brats "an invisible tribe" that makes up 5% of the American population.

The documentary ends with another quote from Pat Conroy:

We spent our entire childhoods in the service of our country, and no one even knew we were there.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |