Missouri Compromise facts for kids

The Missouri Compromise was a law passed by the United States Congress in 1820. It was created to solve a serious disagreement between the northern and southern states about slavery.

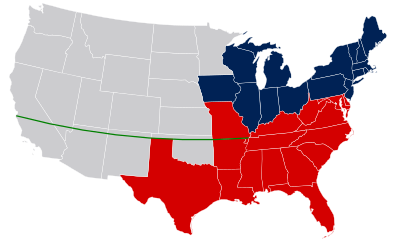

The compromise had three main parts. First, it allowed Missouri to join the Union as a state where slavery was legal. Second, it allowed Maine to join as a free state, where slavery was illegal. Third, it drew an imaginary line across the western territories at the 36°30′ parallel. Slavery would be banned north of this line, but allowed south of it.

This law was passed by Congress on March 3, 1820, and signed by President James Monroe on March 6, 1820. It temporarily settled the argument over the expansion of slavery, but it also showed how deeply divided the country was.

Contents

A Divided Country

The time when the compromise was passed is often called the Era of Good Feelings. This was because there was only one major political party, the Democratic-Republicans. However, this did not mean everyone agreed on all the issues. Big disagreements were growing, especially about slavery.

A major issue was the balance of power in Congress. In 1819, the United States had 22 states. Eleven of them were "free states" where slavery was against the law. The other eleven were "slave states" where slavery was allowed. This created a tie in the U.S. Senate, where each state gets two senators. Because of this tie, neither the North nor the South had enough power to pass laws that the other side strongly opposed.

The country was also growing. In 1803, the U.S. had bought a huge area of land from France called the Louisiana Purchase. As settlers moved into this new land, new territories were formed. When a territory's population grew large enough, it could ask to become a state.

The Missouri Question

In 1819, the people living in the Missouri Territory asked to join the United States as a new state. Most of the settlers in Missouri who had come from the South had brought enslaved African Americans with them. They wanted Missouri to be a slave state.

This caused a crisis. If Missouri joined as a slave state, the South would have more senators than the North (24 to 22). This would break the balance of power and give the southern states an advantage in Congress.

The Tallmadge Amendment

When the bill to make Missouri a state came before the House of Representatives, a congressman from New York named James Tallmadge Jr. added an amendment. The Tallmadge Amendment proposed two things:

- No more enslaved people could be brought into Missouri.

- Children of enslaved people already in Missouri would become free at the age of 25.

This amendment caused a very angry debate. Southern leaders argued that Congress did not have the right to tell a state whether it could allow slavery. They believed it was an issue for each state to decide for itself. Northern leaders did not want to see slavery spread into the new western lands. The House of Representatives, which had more members from the North, passed the bill with the amendment. However, the Senate, where the power was balanced, rejected it. Congress could not agree, and the issue was left undecided.

Crafting the Compromise

When Congress met again in late 1819, the problem had not gone away. But a new opportunity appeared. The people of Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, also wanted to become a state. Since slavery was illegal in Maine, it could join the Union as a free state.

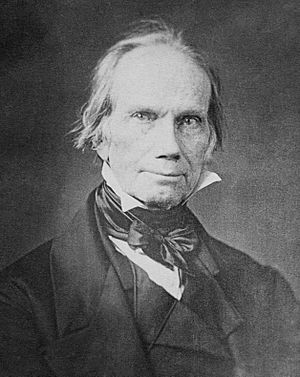

This led to the idea of a compromise. Henry Clay, a powerful congressman from Kentucky, helped lead the effort to find a solution. The final deal, which became known as the Missouri Compromise, had three parts:

- Missouri enters as a slave state. This pleased the South.

- Maine enters as a free state. This pleased the North and kept the balance of power in the Senate at 12 free states and 12 slave states.

- A line is drawn for future states. Slavery would be banned in all future territories from the Louisiana Purchase that were north of the 36°30' latitude line. This line was the southern border of Missouri.

This package of agreements passed both the House and the Senate. It was a close vote, but the compromise became law in March 1820.

The Second Missouri Compromise

A year later, another problem came up. Missouri's new state constitution included a rule that would ban free Black people from entering the state. This angered many northern leaders. Henry Clay once again stepped in and helped create a second compromise. Missouri was admitted to the Union, but only after it promised that its constitution would not be used to take away the rights of any U.S. citizens.

Impact of the Compromise

The Missouri Compromise successfully cooled down a major crisis. For over 30 years, it helped keep the peace between the North and the South. Many people at the time saw it as a vital agreement that saved the Union.

However, the compromise did not solve the problem of slavery. Instead, it drew a clear line across the country, dividing it between a region where slavery was allowed and a region where it was not.

Thomas Jefferson, a former president, was very worried by the compromise. In a famous letter, he wrote that the division of the country was like a "fire bell in the night" that "awakened and filled me with terror." He believed it was the "knell of the Union," meaning a sign that the United States would one day break apart.

For the next few decades, the idea of keeping a balance between free and slave states continued. New states were often admitted in pairs, one free and one slave, to keep the numbers in the Senate equal.

Repeal of the Compromise

The peace created by the Missouri Compromise did not last forever. In 1854, Congress passed the Kansas–Nebraska Act. This law allowed settlers in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. This idea was called "popular sovereignty," and it effectively erased the 36°30′ line from the Missouri Compromise.

The repeal of the compromise caused outrage in the North. It led to the creation of the new Republican Party, which was dedicated to stopping the spread of slavery. A politician from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln became a leading voice against the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

In 1857, the Supreme Court made a ruling in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case. The court said that the Missouri Compromise had been unconstitutional all along because Congress did not have the power to ban slavery in the territories.

These events destroyed the old compromise and pushed the North and South further apart. The deep divisions over slavery would finally lead to the American Civil War in 1861.

See also

In Spanish: Compromiso de Misuri para niños

In Spanish: Compromiso de Misuri para niños