Mixtón War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mixtón War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas and Mexican Indian Wars | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Caxcanes | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Francisco Tenamaztle | |||||||

The Mixtón War (1540-1542) was a big fight by the Caxcan people of northwestern Mexico. They were fighting against the Spanish who had conquered their lands. The war got its name from Mixtón, a hill in Zacatecas. This hill was a strong fort for the native people.

Contents

Who Were the Caxcanes?

While other native groups also fought, the Caxcanes were the main group leading the resistance. The Caxcanes lived in parts of modern-day Jalisco, southern Zacatecas, and Aguascalientes.

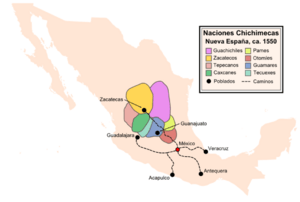

They were often called part of the Chichimeca. This was a general name used by the Spanish and Aztecs for native groups in northern Mexico's deserts. However, the Caxcanes were different. They settled down and grew their own food, living in towns. They were likely the most northern group in Mexico who lived in permanent towns and farmed. The Caxcanes probably spoke a language from the Uto-Aztecan family. Other native groups, like the Zacatecos, also joined the fight.

Why Did the War Start?

The Caxcanes first met the Spanish in 1529. A Spanish leader named Nuño de Guzmán marched through the area. He had 300-400 Spanish soldiers and thousands of Aztecs and Tlaxcalan allies.

For six years, Guzmán was very harsh. He killed, tortured, and enslaved many native people. His goal was to scare the natives by being cruel. Guzmán and his officers started Spanish towns in the region, which they called Nueva Galicia. One of these towns was Guadalajara, near the Caxcanes' homeland. But as the Spanish moved further north, they faced more resistance. They tried to force natives to work for them using a system called encomienda.

The Mixtón War Begins

In the spring of 1540, the Caxcanes and their allies fought back. They might have felt stronger because many Spanish soldiers had left. Governor Francisco Vázquez de Coronado had taken over 1,600 Spanish and native allies north on an expedition. This left the area with fewer experienced soldiers.

The war began when 18 rebellious native leaders were arrested. Nine of them were executed in mid-1540. Later that year, natives killed a Spanish landowner named Juan de Arze. Spanish leaders also noticed that the natives were doing "devilish" dances. After killing two Catholic priests, many natives left their forced labor farms. They hid in the mountains, especially at the strong hill fort of Mixtón.

The acting governor, Cristóbal de Oñate, led Spanish and native forces to stop the rebellion. The Caxcanes killed a group of one priest and ten Spanish soldiers. Oñate tried to attack Mixtón, but the natives on the hill fought him off. Oñate then asked for more soldiers from Mexico City.

The main leader of the Caxcanes was Francisco Tenamaztle from Nochistlán, Zacatecas.

Key Battles and Leaders

The Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza asked the famous Spanish conqueror Pedro de Alvarado for help. Alvarado decided not to wait for more soldiers. In June 1541, he attacked Mixtón with 400 Spanish and many native allies. He faced about 15,000 natives led by Tenamaztle and Don Diego. The Spanish attack failed, and 10 Spanish soldiers and many native allies were killed. Alvarado's later attacks also failed. On June 24, Alvarado was hurt when a horse fell on him. He died on July 4.

Feeling confident, the natives attacked the city of Guadalajara in September. But they were pushed back. The native army then went back to Nochistlán and other strongholds. The Spanish leaders were very worried. They feared the revolt would spread.

They gathered a huge force: 450 Spanish soldiers and 30,000-60,000 Aztec, Tlaxcalan, and other native allies. Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza led this army into the Caxcanes' land. With his much larger force, Mendoza captured the native strongholds one by one. On November 9, 1541, he took the city of Nochistlán and captured Tenamaztle. However, the native leader later escaped. Tenamaztle continued to fight as a guerilla until 1550. In early 1542, the Mixtón fort fell to the Spanish, and the rebellion ended.

After the defeat, many native people faced harsh treatment. Thousands were forced to work in mines. Many survivors, mostly women and children, were moved from their homes to work on Spanish farms. The viceroy even ordered the execution of men, women, and children. Reports of this extreme violence led to a secret investigation into the viceroy's actions.

What Happened After the War?

The Spanish victory in the Mixtón War allowed them to control the area where Guadalajara, Mexico’s second largest city, is located. It also opened up the northern deserts for the Spanish. There, explorers would later find rich silver deposits.

After their defeat, the Caxcanes became part of Spanish society. They lost their unique identity as a separate people. They later helped Spanish soldiers as they continued to move north.

Spanish expansion after the Mixtón War led to an even longer and bloodier conflict. This was the Chichimeca War (1550–1590). The Spanish learned from the Mixtón War. They had to change their approach from forcing natives to surrender to trying to get along with them. This process of gradual blending took centuries.

The Caxcanes might still exist today, at least in folk festivals. They are possibly the Tastuane people. Annual festivals of the Tastuanes in towns like Moyahua de Estrada, Zacatecas, remember the Mixtón War.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra del Mixtón para niños

In Spanish: Guerra del Mixtón para niños