National Natural Landmark facts for kids

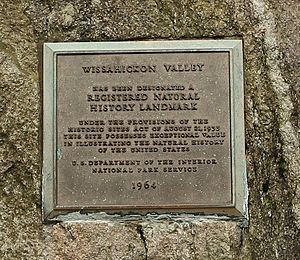

The National Natural Landmarks (NNL) Program helps find and protect amazing natural places across the United States. It's the only program that officially recognizes the best examples of biological (living things) and geological (earth features) sites. These special places can be on land owned by the public or by private citizens.

This program started on May 18, 1962, thanks to United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. Its main goal is to encourage people to voluntarily protect sites that show the incredible geological and ecological story of the U.S. It also helps everyone appreciate our country's natural treasures more.

As of August 2025, there are 605 sites on the National Registry of Natural Landmarks. These important natural spots are found in 48 states, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The National Park Service runs the NNL Program. They can also help owners and managers take care of these sites if asked. The program does not aim for the government to buy these lands. National Natural Landmarks are important places owned by many different people and groups. Joining this program is completely up to them.

The NNL Program is based on a law called the Historic Sites Act from 1935. Being named an NNL means the owner agrees to protect the special natural features of their site as much as possible. The owner is fully responsible for managing and preserving their landmark. Either the owner or the government can end this agreement after telling the other party.

Contents

How a Place Becomes a National Natural Landmark

Becoming an NNL is a careful process. The Secretary of the Interior makes the final decision. This happens after scientists study a potential site very closely. The owner must also agree to the designation. To be considered, a site must be one of the best examples of natural features in its region.

Here are the steps involved in choosing a new NNL:

- Scientists first look at a natural area to find the most promising sites.

- Landowners are told that their site is being considered for NNL status. Then, different scientists visit the site for a detailed check.

- Other experts review this evaluation report to make sure it's accurate.

- Staff from the National Park Service also review the report.

- The Secretary of the Interior's National Park Advisory Board checks if the site truly qualifies as an NNL.

- The findings go to the Secretary of the Interior, who decides to approve or decline the site.

- Finally, landowners are told a third time if their site has been named an NNL.

Places that can become NNLs include land and water ecosystems. They also include geological features like rocks, landforms that show how the Earth changes, or parts of Earth's history. Even fossil evidence of how life has changed over time can be an NNL. For example, a "Lakes and ponds" theme could include deep lakes, crater lakes, or even swamps and marshy areas.

Who Owns National Natural Landmarks?

The NNL program does not require special properties to be owned by the government. Many types of owners have NNLs on their land. This includes federal, state, local, city, and private owners.

Federal lands with NNLs are managed by groups like the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service. Some NNLs are also on lands belonging to Native American tribes. State lands with NNLs can be forests, parks, or game refuges.

Private lands with NNLs belong to universities, museums, and conservation groups. They can also be owned by businesses or private individuals. About 52% of NNLs are managed by public agencies. More than 30% are completely privately owned. The rest (18%) are a mix of public and private ownership.

Visiting National Natural Landmarks

Being an NNL doesn't mean a place has to be open to the public. Many NNLs are open for tours, but others are not. Since many NNLs are on federal and state land, you often don't need special permission to visit.

Some private NNLs might be open to visitors or just need permission from the manager. However, some private owners don't want any visitors at all. They might even take legal action against trespassers. This could be because of possible damage, dangerous areas, or simply a wish for privacy.

What NNL Status Means for Property Owners

NNL designation is an agreement between the property owner and the U.S. government. It does not change who owns the property. It also doesn't add any new burdens or rules to the land. If the property changes owners, the NNL status does not automatically transfer.

Joining the NNL Program means landowners promise to keep their NNL property in its natural state. If a landowner plans to make big changes that would harm the habitat or landscape, being part of the program wouldn't make sense.

The NNL designation itself doesn't create new land use rules. State or local governments could, on their own, create rules or zoning laws that might affect an NNL. However, as of 2005, no such cases have been found. Some states do require planners to know where NNLs are located.

List of Landmarks

Here is a list of National Natural Landmarks, organized by state or territory. As of August 2025, there are 605 landmarks.

| State or territory | Number of landmarks | Number, non-duplicated | Earliest declared | Latest declared | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 7 | 7 | October 1971 | November 1987 |  |

| Alaska | 16 | 16 | 1967 | 1976 |  |

| American Samoa | 7 | 7 | 1972 | 1972 |  |

| Arizona | 10 | 10 | 1965 | 2011 |  |

| Arkansas | 5 | 5 | 1972 | 1976 |  |

| California | 37 | 37 | 1964 | January 2021 |  |

| Colorado | 17 | 16 | 1964 | 2023 |  |

| Connecticut | 8 | 7 | April 1968 | November 1973 |  |

| Delaware | 0 | ||||

| Florida | 18 | 18 | March 1964 | May 1987 |  |

| Georgia | 11 | 11 | 1966 | April 2013 |  |

| Guam | 4 | 4 | 1972 | 1972 |  |

| Hawaii | 7 | 7 | June 1971 | December 1972 |  |

| Idaho | 11 | 11 | 1968 | 1980 |  |

| Illinois | 18 | 18 | 1965 | 1987 |  |

| Indiana | 30 | 29 | 1965 | 1986 |  |

| Iowa | 7 | 7 | 1965 | 1987 |  |

| Kansas | 5 | 5 | 1968 | 1980 |  |

| Kentucky | 7 | 6 | 1966 | 2009 |  |

| Louisiana | 0 | ||||

| Maine | 14 | 14 | 1966 | 1984 |  |

| Maryland | 6 | 5 | 1964 | 1980 |  |

| Massachusetts | 11 | 10 | October 1971 | November 1987 |  |

| Michigan | 12 | 12 | 1967 | 1984 |  |

| Minnesota | 8 | 7 | 1965 | 1980 |  |

| Mississippi | 5 | 5 | 1965 | 1976 |  |

| Missouri | 16 | 16 | June 1971 | May 1986 |  |

| Montana | 10 | 10 | 1966 | 1980 | |

| Nebraska | 5 | 5 | 1964 | 2006 |  |

| Nevada | 6 | 6 | 1968 | 1973 |  |

| New Hampshire | 11 | 11 | 1971 | 1987 |  |

| New Jersey | 11 | 10 | October 1965 | June 1983 |  |

| New Mexico | 12 | 12 | 1969 | 1982 |  |

| New York | 29 | 27 | March 1964 | 2023 |  |

| North Carolina | 13 | 13 | 1967 | 1983 |  |

| North Dakota | 4 | 4 | 1960 | 1975 | |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 0 | ||||

| Ohio | 23 | 23 | 1965 | 1980 |  |

| Oklahoma | 3 | 3 | December 1974 | June 1983 | |

| Oregon | 11 | 11 | 1966 | June 2016 |  |

| Pennsylvania | 27 | 27 | March 1964 | January 2009 |  |

| Puerto Rico | 5 | 5 | 1975 | 1980 |  |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 1 | May 1974 | May 1974 |  |

| South Carolina | 6 | 6 | May 1974 | May 1986 |  |

| South Dakota | 13 | 12 | 1965 | 1980 |  |

| Tennessee | 13 | 13 | 1966 | 1974 |  |

| Texas | 21 | 21 | 1965 | 2024 |  |

| Utah | 4 | 4 | October 1965 | 1977 |  |

| Vermont | 12 | 11 | 1967 | 2009 |  |

| Virgin Islands | 7 | 7 | 1980 | 1980 |  |

| Virginia | 10 | 10 | 1965 | 1987 |  |

| Washington | 18 | 18 | 1965 | 2011 |  |

| Washington D.C. | 0 | ||||

| West Virginia | 16 | 15 | 1964 | 2021 | |

| Wisconsin | 18 | 18 | 1964 | May 2012 |  |

| Wyoming | 6 | 5 | October 1965 | December 1984 |  |

See also

In Spanish: Hito natural nacional para niños

In Spanish: Hito natural nacional para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |