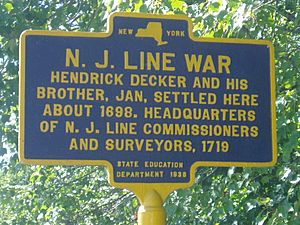

New York – New Jersey Line War facts for kids

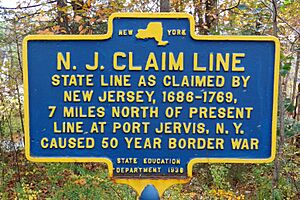

The New York – New Jersey Line War was a series of small fights and raids. These happened for over 50 years between 1701 and 1765. The fights were over the border between two early American colonies: New York and New Jersey.

Border disputes were common when colonies were first settled. This happened because of unclear maps, old rules, or just people ignoring boundaries. Local settlers often got into conflicts until a final agreement was made. In this big fight, about 210,000 acres (850 km2) of land were at stake.

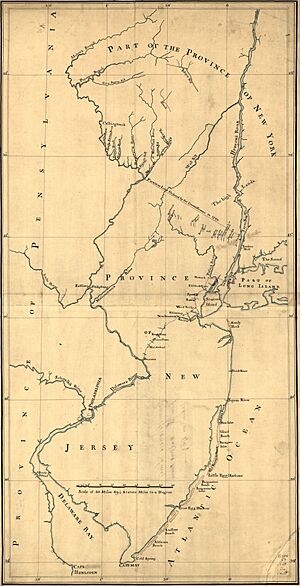

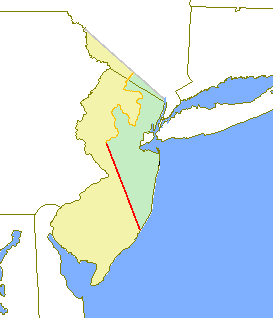

The original western and northern border of New Jersey was set in 1664. It was supposed to run along the Delaware River north to a point at 41 degrees, 40 minutes latitude. From there, it would go in a straight line to 41 degrees latitude on the Hudson River. This border was agreed upon by both New York and New Jersey by 1719.

However, settlers from New York moved west from Orange County. They did not respect New Jersey's northern boundary. This led to conflicts between settlers from both sides. Also, these settlers had to fight Native Americans who raided the area during the French and Indian War.

The last big fight happened in 1765. New Jersey settlers tried to capture the leaders of the New York group. Since it was the Sabbath (a day of rest), neither side used weapons. The New York leaders were captured and held briefly in the Sussex County jail.

The conflict was finally settled by King George III. In 1769, he appointed a group of people to set the permanent border. This new border runs southeast from the Tri-States Monument near Port Jervis, New York to the Hudson River. Both New York and New Jersey approved this new border in 1772. The King officially approved it on September 1, 1773.

Contents

Early Colonial Beginnings

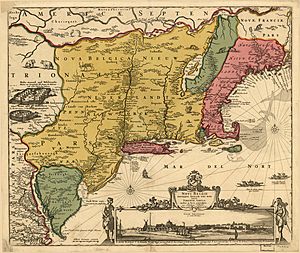

In 1665, Colonel Richard Nicolls, the Governor of New York, learned important news. James, the Duke of York, had given a special paper (a charter) for New Jersey to two friends. These friends were Sir George Carteret and John Lord Berkeley.

Governor Nicolls quickly realized that New York would lose valuable land. He wrote to the Duke, explaining that the New Jersey land was very good. It had fertile soil, was near the Hudson River, and might even have rich mines. He felt this loss would stop people from wanting to live under the Duke's rule in New York.

Nicolls thought someone had tricked the Duke. He believed a man named Captain Scott was causing trouble. Scott wanted the same land the Duke had. Nicolls felt Scott had tricked Berkeley and Carteret into a plan that would ruin New York's chances to grow. He hoped the Duke would fix this problem.

So, from the very start, New York's leaders knew they had lost a valuable area. Governor Nicolls and later governors wanted New Jersey back. Or, at least, they wanted something in return for its loss. New York had an advantage in this argument. The Duke's charter for New Jersey was based on a map from 1654 by Nicolas Johannis Visscher.

This map, called the Jansson–Visscher map, showed the northernmost branch of the Delaware River at 41 degrees, 40 minutes North latitude. Based on this, the Duke set the northern border points for New York and New Jersey. The border was to go "to the Northward as far as the Northernmost branch of the said Bay or River of Delaware, which is forty one Degrees and forty minutes of Latitude and crosseth over thence in a straight line to Hudson's River in forty one Degrees of Latitude."

If a branch of the Delaware River had been at 41°40′, the border would have been clear. But no such branch existed there. New York used this confusion to delay setting the exact border. They hoped New Jersey, being smaller and less powerful, would have to agree to a border farther south. This map mistake caused problems starting in 1676. The dispute finally ended in 1769 when a special group set a compromise border.

Early Attempts to Survey the Border

The first try to find New Jersey's northern border was in 1684. Governors Thomas Dongan of New York and Gawen Lawrie of New Jersey met near Tappan on the Hudson River. They agreed to place the eastern border point at the mouth of Tappan Creek. They also said surveyors would soon draw the line to the Delaware River.

Records from New York in 1684 show that Native Americans were told to watch the surveyors. They were also told to sell land north of the line only to New Yorkers. A New Jersey deed from 1685 also mentioned a location "at Tappan Creek upon the Hudson's River at the line of Division agreed upon by the Governors of the two provinces."

Years later, Governor Robert Morris of New Jersey talked about this meeting. He said that Governor Dongan and Governor Lawry met around 1685 or 1686. They made a latitude measurement and marked a beech tree with a pen knife. Morris said they agreed that Tappan Creek's mouth would be the border point on the Hudson River.

However, not much happened after this meeting. There is no clear proof that a survey was finished. In 1754, New York claimed a survey was done in 1684. They said the northern point was at the southern end of Minisink Island. But New York never showed this proof.

It wasn't until 1686 that New York and New Jersey agreed to survey the line. George Keith (East New Jersey), Andrew Robinson (West New Jersey), and Philip Wells (New York) met on the Delaware River. Wells was told to start the line at 41 degrees, 40 minutes latitude on the Delaware. Then, they were to go to the Hudson River and find 41 degrees latitude.

Historians believe the western point was near the modern 41°40′ location. But there was much debate about the eastern point. New Jersey later claimed it was 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Tappan Creek. However, most records suggest Tappan Creek's mouth was the agreed point. Still, a real border line was never drawn.

One reason might be a letter from Daniel Coxe in 1687. He said New Jersey should not have agreed to a division without a very exact survey. He believed New York and East Jersey had better maps and were trying to get more land. He also said they wouldn't print their maps until they settled things with West New Jersey.

There is no proof that an agreement was ever reached. No clear border line was set at that time. But this confusion didn't stop people from settling the areas. In fact, competing colonial governments might have even encouraged it. They wanted to claim control over the land.

Growing Settlements and Border Problems

By the mid-1680s, settlements slowly began on the eastern side of the border, along the Hudson River. In 1685, New Jersey leaders leased land near Tappan Creek to the Lockhart family. New Jersey later claimed that New York's Governor Dongan gave land grants on New Jersey's side of Tappan Creek in 1686. He then forced New Jersey landowners to pay New York for the same land or leave. It was even said that Dongan made New York's land grants one day earlier than New Jersey's. This was done so they could be used as proof in future land disputes. These actions caused a lot of uncertainty for settlers and landowners.

The first settlement on the western border began in 1690. The town of Port Jervis was founded on the Delaware River by several families.

Even though the governments did little to set a firm border, more settlements meant more confusion. The border dispute grew more complicated.

In 1693, Governor Hamilton of New Jersey wrote to Governor Fletcher of New York. He again said the eastern border point was at Tappan Creek. Hamilton asked for a joint survey to correctly collect taxes and start military training. New York's Council discussed this but made no decisions. New Jersey's leaders, frustrated by New York's inaction, decided in 1695 to do the survey themselves. But it wasn't done until 1719.

The 1690s saw more settlements along the border. Much of this was because New York was giving out land. New York hoped that by having more settlers, this unofficial border would become the final one.

Captain Arent Schuyler was one of the first to benefit. He explored the Minisink region for New York in 1694. He liked the area so much that he returned in 1697 to settle on 1,000 acres (4 km2) given to him by Governor Fletcher. Fletcher also gave land to others in the Minisink region and on the eastern end of the border. New Jersey also gave land in the disputed area. But New York's efforts were more successful. By 1701, the Minisink area had enough people to hold an election as part of Ulster County, New York.

Friction and Open Conflict

More settlements along the border naturally led to problems between settlers from each colony. The first reports of trouble appeared in 1700. An act passed by New York's Council dealt with a dispute between two New York residents. One complained that the other wasn't honoring their land agreement in the Minisink Country. The Council asked Governor Bellomont of New York to look into the growing problems between New York and New Jersey residents along the border.

Governor Bellomont asked for help from the Board of Trade in London. The Board said they would "give some order" and asked for a report. However, Bellomont died before the letter reached him. His replacement decided to ignore the offer of help. He knew settling the dispute would reduce his power and stop him from giving out land in the disputed area. So, he did not try to set the border.

The confusion and lack of control by New Jersey's leaders, especially with land disputes, gave Queen Anne a reason to take away New Jersey's control from them. She united East and West New Jersey with New York on April 15, 1702. This lasted until 1738, when New Jersey became separate again. The border dispute helped New York gain more control. New York's governors had no reason to rush to solve the border problem.

In 1703, Lord Cornbury became Governor of New York and New Jersey. He told New York's Assembly that New York's loss of New Jersey was permanent. But he said New York should get something in return. Cornbury encouraged New York to keep giving out land. He hoped this would force New Jersey to give New York compensation to settle the border dispute. Cornbury began giving out "floating patents" for land. The size of these patents depended on where New York's southern border with New Jersey ended up. This made the situation even worse. Settlers tried to limit settlement either north or south of their land to make their own patents bigger.

The Wawayanda and Minisink Land Grants

The Wawayanda Patent was the first of these "floating patents." It was given in 1703 to John Bridges and his company, who were friends of Governor Cornbury. It was meant to cover between 60,000 and 350,000 acres (240 to 1,400 km2), depending on where the border ended up. In 1704, the larger Minisink Patent was given to Matthew Ling and his company, also friends of Cornbury. This patent included 160,000 acres (650 km2) of disputed land. A smaller Cheescocks Patent was granted in 1707. To show New York's claim over this area, Orange County, New York, was created in 1709.

In 1705, Peter Fauconnier, a tax collector in New Jersey, told Lord Cornbury that people living along the border were "neither here nor there" regarding their residency. In 1709, Fauconnier wrote again, explaining more problems. He said citizens were being taxed twice and forced to serve in both colonies' militias. He also reported that squatters and illegal land users found the border confusion helpful. But their presence was not good for either colony.

However, this increasing confusion did not stop settlement. The Wawayanda Patent was first settled in 1712. By 1716, the Minisink Patent (known as Walpack in New Jersey) had enough settlers to support the first clergyman.

Pressure to Resolve the Dispute

In 1717, James Alexander became Surveyor of New Jersey. He owned 1,000 acres (4 km2) along the disputed border. He wrote to friends in England about New Jersey's great potential. He also worried about the threat from the border dispute. He became a leader in New Jersey's efforts to get the border decided fairly.

In 1717, New York's Governor Hunter decided it was time to reduce tensions and solve the border dispute. He added a rule to New York's 1717 debt bill. This rule allowed an official survey of the line, if New Jersey agreed on the exact location. Some people, like Peter Schuyler (Arent's son) and Stephan DeLancey, tried to stop this bill because of the cost to taxpayers. Also, a group of London merchants asked the King to stop it. They believed losing any part of New York would hurt their business. They reminded the King that he would lose money and that the Minisink Patent was important to New York. But their attempts failed.

On April 19–20, 1717, Governor Hunter spoke to the New Jersey Assembly. He told them about his efforts to end the dispute and New York's debt bill. New York gave him the power to appoint people to settle the matter. Hunter said his goal was "to prevent future Disputes and Disquiet and to do Justice to the Proprietors on the Borders." On March 27, 1719, the New Jersey Legislature passed "An Act for Running and Ascertaining the Division Line betwixt this Province and the Province of New York."

New Jersey appointed Dr. John Johnston, George Willocks, and James Alexander as commissioners. They were tasked with finding the true northern point from the Duke of York's 1664 deed. New York's Assembly also appointed commissioners, led by Allane Jarrat. Their job was to "find out that place of the said northernmost branch of Delaware River that lies in the latitude of forty-one degrees and forty minutes." This instruction was very specific. It limited Jarrat to finding the northern point at 41°40′, not necessarily the northernmost branch of the entire Delaware River. The King had not yet approved the 1717 debt bill. But Governor Hunter, believing much had been done, allowed the expedition to start. He then left for London in June 1719 to help get the bill passed.

Commissioners from both colonies met on June 22, 1719, on the Delaware River. Reports say Allane Jarrat was difficult from the start. John Reading, one of New Jersey's surveyors, wrote in his journal on June 30 that Jarrat "wholly declined" continuing the survey.

Even with Jarrat's lack of cooperation, the final camp was reached on July 8. It was on the Delaware, 35 miles (56 km) north of the "Mahakkamack" branch. By July 17, a smaller group led by Captain Harrison, which had been looking for branches farther north, arrived. They reported no major northern branch of the river. However, they found the small Popaxtun Branch, which is at 41°55′ today. On July 18, the whole expedition was threatened by an argument between Jarrat and Alexander. Reading's Journal says the surveyors disagreed about how to calculate positions.

Things did not get better. On July 22, 1719, New York settlers verbally abused the commissioners. But the commissioners reached a final agreement on July 25, called the "Tri Partite Deed." This agreement placed the northern point upstream of an Indian village called Casheightouch, now Cochecton, New York. The latitude there was set at 41°40′. The surveyors accepted the "Fishkill" (which was the main Delaware River north of the Mackhackimack branch) as the northernmost branch. This seemed like a compromise for New York, as the smaller Popaxtun branch was actually farther north.

The "Tri Partite Deed" was signed two days later, on July 27, 1719, along the Hudson River. Surveys placed the eastern point 5 miles (8 km) north of Tappan Creek. But before the final survey of the agreed line could be done, Mr. Walter, a New York Commissioner, reported feeling ill. The expedition was stopped until September. Many of New York's commissioners went to New York City.

New York Changes Its Mind

In New York City, the commissioners spoke to friends who owned property along the border. These included Stephan DeLancey, Lancaster Symes, and Henry Wileman. The commissioners told them that the "Tri Partite Deed" would mean New York would lose a large part of the Minisink and Wawayanda patents. It would also lose the town of Orangetown (Tappan) and most of the Kakiate and Cheescock patents. On August 20, these important men, who knew about the agreement early, asked New York's Council President, Peter Schuyler, for land to make up for their expected losses.

But this request for compensation quickly changed. They now wanted New York to fight to keep the land. In early September 1719, Allane Jarrat told New York's Council that the surveying tools used were wrong. He said his conscience would not let him accept the "Tri Partite Deed." Jarrat claimed he didn't want to rely on his own judgment in such an important matter that affected so many people's land. He asked the Council for advice on how to proceed now that these errors were known.

On the same day, another request came from "several inhabitants" of New York. They owned land near the border. This second request supported Jarrat's claims. It reminded the Council of an earlier agreement (1694) that placed the eastern point at Tappan Creek. It also accused Captain Harrison of lying about there being no other branches farther north on the Delaware. They asked that the final survey be stopped until the King decided on the 1717 debt bill. Finally, they offered to pay half the cost for a more accurate surveying tool. This request was signed by 43 people, including powerful men like DeLancey, Wileman, Symes, and leaders from Orange County. These were influential men who could easily make life difficult for Allane Jarrat.

The fact that these requests arrived on the same day suggests that these important gentlemen, worried about losing their land, convinced Jarrat to back out of the agreement. There was clearly a plan to defeat the "Tri Partite Deed." With Governor Hunter in London, Peter Schuyler and other powerful New York leaders took control.

These New York gentlemen were also worried because they realized the disputed border lands had valuable iron ore, water power, and forests for charcoal. On September 29, New York's Council passed a resolution. It said they could not advise Jarrat to continue with the survey. Instead, he should state that the point set at the Fishkill was wrong. This was to make sure New York would not be harmed by the "Tri Partite Deed." They also said all further work should stop until a better surveying tool was found. This resolution not only told Jarrat to back out but also told him to prove the point at the Fishkill was wrong.

New Jersey's Response

New Jersey's leaders were shocked and angry by New York's actions. James Alexander wrote that he could "scarcely think he was earnest" when Jarrat wrote his request to the Council. New Jersey was also worried about finding a more accurate surveying tool. John Barclay wrote that it was impossible to make a perfectly true tool. If the line had to wait for one, it would "be stay'd for ever."

On September 29, 1719, New Jersey's leaders wrote to Robert Morris. They were concerned that the effort to set the border might be stopped. They felt it was based on "groundless, weak, and untrue suggestions" and the "visionary whim" of the surveyor. This was after both colonies' governments had ordered the survey and spent a lot of money.

In this letter, New Jersey's leaders explained their side of the story about the "Tri Partite Deed" agreement. They argued:

- New York was wrong about the Duke of York's latitude tables being inaccurate. His tables were reliable, and he knew the consequences of setting the latitude exactly.

- If there had been a branch farther north on the Delaware, Captain Harrison would have reported it. It would have helped New Jersey. If the small Poxitun branch had been called the northernmost, New Jersey would have gained 300,000 more acres.

- The agreement between Governors Hamilton and Fletcher in 1694, which set the eastern point at Tappan Creek, was weak. It was written almost seven years after the original survey. Also, the point set in 1684, which was farther north, was found using a very accurate six-foot surveying tool.

- If there was an error in the tools, it could have been to the south just as easily as to the north. Finding a more accurate tool was very unlikely.

- The original 1717 debt bill, which allowed the survey, was legal for both colonies.

- New York's Governor Dongan had illegally given away property at Tappan to claim the area.

- Allane Jarrat had lied and was not even present when the final measurements were taken on the Hudson. James Alexander said Jarrat never claimed the errors couldn't be fixed. Even though Jarrat was difficult, he was satisfied with the measurements before leaving for New York City.

The letter ended by suggesting an investigation to look into the whole case. While no investigation happened, proof showed that some money for the New York expedition was used improperly. But nothing much came of that report either. In November 1719, Allane Jarrat was rewarded for stopping the "Tri Partite Deed." He was named Surveyor General of New York and given hundreds of acres of land in western New York.

Open Warfare Along the Border

In 1720, the original 1717 debt bill, which started all these events, was finally approved by the King. By this time, the "Tri Partite Deed" was completely dead. Governor Hunter was no longer in charge. Robert Morris, not wanting to give up, wrote to Peter Schuyler. He reminded him how important it was to set and survey the line exactly. He said this was "Visible to all not willfully blind or whose frauds and Encroachments on either side have made it their interest to oppose it."

Tension along the border reached a breaking point. Open fights began. By 1720, Thomas and Jacobus Swartwout of New York and John and Nicholas Westphalia of New Jersey were burning each other's crops. They claimed the others didn't own their land properly. This small battle and many worse ones would happen over the next 49 years. This continued until a final line was drawn by the King's special group in 1769. During these years, New York kept trying to delay the final decision. Every legal trick was used. The whole dispute eventually went to the Board of Trade in London, where it stayed for years. New Jersey never quite became strong enough to defeat New York and get the border they believed was theirs.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |