Newmarket Canal facts for kids

The Newmarket Canal is an old, unfinished canal project in Newmarket, Ontario. It was also called the Holland River Division. This canal was planned to be about 10 miles (16 km) long. It would have connected Newmarket to the Trent–Severn Waterway through the East Holland River and Lake Simcoe.

Construction was almost finished when the project was stopped. Today, you can still see three completed locks, a swing bridge, and a turning basin.

The canal was first suggested to help businesses in Newmarket. They were paying high fees to use the Northern Railway of Canada. These fees made it hard for them to compete. However, the canal's economic benefits were questionable. The Trent-Severn Waterway ended far from Toronto, while Newmarket was much closer to the city. Also, not many boats were expected to use the canal, maybe only two or three barges a day.

The main reason for the canal was to bring money to the area of York North. This area was represented by William Mulock, a powerful member of the Liberal Party of Canada. Everyone knew it was a patronage project, meaning it was built to gain political support. The newspapers and the House of Commons of Canada often criticized it.

When construction began in 1908, engineers found there wasn't enough water to keep the canal working well in summer. People started making fun of it, calling it "Mulock's Madness".

The canal became an example of what the Conservative Party called wasteful spending by the Liberals. When Robert Borden and the Conservatives won the 1911 Canadian federal election, they took over the Department of Railways and Canals. They quickly stopped the construction. Today, local people call it "The Ghost Canal".

Contents

History of the Canal

Early Water Travel

The East Holland River flows through Newmarket. For a long time, it was part of the Toronto Carrying Place Trail. This trail connected Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe and then to Georgian Bay. Newmarket was founded in 1796 because of its location on this important water route.

After the War of 1812, William Roe and Andrew Borland set up a fur trading post on the riverbank. They told trappers they could sell their goods there, saving them a long trip to York (now Toronto). This "new market" gave the town its name. Roe stayed and built a store with a dock for traders.

Later, there were plans for a canal called the Toronto and Georgian Bay Canal. It would have ended on the Humber River in Toronto. These plans didn't happen but showed that people were thinking about canals in the area.

The Idea for the Canal

Newmarket grew quickly before the 1900s, thanks to William Mulock. He was a Liberal politician and a close helper of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier. Mulock used his power to bring many factories to Newmarket. These factories were built along the Northern Railway of Canada line, which followed the river valley. You can still see signs of these old industries today. For example, Fairy Lake was once a lumber mill's pond, and the Tannery Mall used to be the Davis Leather Company.

In 1888, the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) took over the Northern Railway. In 1904, they raised their shipping prices. They also charged the full price to Toronto for deliveries anywhere along the line. This meant Newmarket businesses had to pay more to get their goods to market. This extra cost would add thousands of dollars a year, and factories worried they would go out of business. Business leaders tried to change the GTR's mind, but it didn't work. So, people started looking for other ways to transport goods.

At this time, the Trent-Severn Waterway was almost finished. But it was becoming clear that canals were less important than railways for shipping. Even when tolls were removed from the Erie Canal in the US, business didn't improve. The idea of using the Trent-Severn for shipping was no longer the main goal. It was completed more for political reasons and to get water for hydroelectricity.

Mulock suggested a short canal from Holland Landing to Newmarket. He even thought about extending it to Aurora. South of Aurora, the Oak Ridges Moraine hills would make building a canal very hard. The canal's usefulness was questioned because not many goods were shipped north. It would not be very helpful for sending finished goods back to market. Mulock came up with ideas to increase traffic, like shipping oats through the Trent-Severn to a company in Peterborough.

In September 1904, Mulock met Newmarket's mayor, Howard S. Cane, on a train. Mulock shared his canal idea, and Cane was excited. They quickly organized a town meeting, and 300 people showed up. Everyone agreed to two proposals: one for the canal to Newmarket and Aurora, and another to widen parts of the Holland River. People then signed a petition and sent it to the government in January.

Walsh's Survey and Plans

Two weeks after the meeting, a temporary company hired E.J. Walsh to design the canal. Walsh was a skilled engineer who had worked on many big projects. He felt he had been treated unfairly by the government's hiring system.

Mulock announced that Walsh had been hired even before the company was fully formed. Walsh arrived in Newmarket in October 1904. He took his time with the survey, even though Mulock pushed him to hurry. He spent two months taking careful measurements. It was clear that getting enough water would be a big problem.

In January 1905, Mulock asked Walsh for a cost estimate. Walsh estimated it would cost $328,825. This was a shock because it was too expensive to hide in the Trent-Severn budget. This meant Mulock would have to ask Parliament for money for a separate project, which could lead to it being canceled. Mulock then arranged for Newmarket businessmen to meet with Prime Minister Laurier. Laurier seemed very interested in the project.

Mulock faced criticism in the House of Commons of Canada. Conservatives called the canal a "bribe to the electors of North York." The Minister for Railways and Canals, Henry Emmerson, ordered Walsh to make a cheaper estimate. Walsh was worried he would be blamed for cost overruns, so he kept delaying.

In March 1905, Walsh was told to create a new plan with the lowest possible costs. He agreed only after being promised he wouldn't be held responsible for the estimates. He made small changes, like using more wood instead of concrete. These changes lowered the price by $37,000, bringing it under $300,000. He then started detailed construction planning in June. After this, plans to extend the canal to Aurora were dropped.

Political Changes and Problems

Mulock became unhappy with the Liberal Party and retired in 1905 due to health reasons. A new election was held, and Allen Bristol Aylesworth won, but with fewer votes than Mulock. This showed that the public was starting to support the Conservative party. Mulock was appointed Chief Justice of the Exchequer and remained involved in the canal project.

In July 1905, M. J. Butler became the Deputy Minister and Chief Engineer of the Department of Railways and Canals. There was a lot of bad feeling between Walsh, Mulock, and Butler. Butler and his friend Michael John Haney were "railway men" and didn't like Mulock's involvement in the department. Walsh felt Butler was not a good engineer and that his appointment was political.

Dredging Starts and Stops

By January 1906, the Department of Railways and Canals told Walsh to plan for dredging the Holland River. Walsh wanted it 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, but Butler ordered it to be 6 feet (1.8 m) deep, like the rest of the Trent system. In April 1906, a company called The Lake Simcoe Dredging Company won the contract. The owners had no experience in dredging.

The company bought a small boat and started building a large digging machine. An engineer reported this, but Butler said it would be "a circus" because the machine was too big for the boat. They finally started digging in November, but the river froze within three weeks. They tried again in the spring of 1907 but only dug a small amount. They gave up, and their contract was canceled in May 1908.

Walsh's Final Plans

Walsh gave his final plans for the second part of the canal in September 1906. It was similar to his earlier ideas, using the same lock size as the Trent system. To deal with the water shortage, Walsh added large piers to create small lakes at the entrance of each lock. These were built from strong wooden poles covered with planks. He also planned to use three earthen dams to send water from local creeks into the canal. The whole canal would be lined with a clay mixture called puddle to prevent water from leaking out.

Walsh planned for four bridges: two existing wooden bridges would be raised, and two new swing bridges would be built.

The biggest problem was still the lack of water. Walsh suggested using Lake Wilcox as a reservoir. Lake Wilcox is south of Aurora and usually drains into the Humber River. A dam would raise its water level and provide a steady flow of water to the canal. A small channel would connect Lake St. George (which is linked to Lake Wilcox) to the Holland River.

Walsh estimated the total cost for this part of the canal and the Lake Wilcox channel. These figures included money for buying land and moving a railway line.

Grant's Changes and Higher Costs

When Walsh presented his plans, Butler gave them to Grant to review. Grant completely redesigned the canal, making changes that seemed to have no good reason and doubled the cost. Walsh later said that Grant "mutilated the plans." Some people believe this was done on purpose to make the plan look bad and make Walsh look foolish.

Grant changed many things. He wanted to use concrete everywhere, even for piers and dams, instead of timber. He also wanted to dredge the entire route deeper and wider. He made the locks longer, from 143 feet (44 m) to 175 feet (53 m). This change didn't make sense because the rest of the Trent system used 143-foot (44 m) locks. He also replaced the simple lock valve system with a more complex one, which made the lock walls much thicker. He replaced two smaller locks with one large 20-foot (6.1 m) lock, which also needed thicker walls.

These changes greatly increased the cost. When the first dredging efforts failed, Grant ordered a new survey. He suggested cutting a channel to the deeper western branch of the Holland River. This new plan more than doubled the estimated cost for the first part of the canal. Grant's final report was sent to Butler in December 1906.

Walsh wrote a strong letter to Butler in January 1907, criticizing every change Grant made. He said Grant's changes would "enormously increase the aggregate cost of the work, lessen the water storage for supply purposes, and substitute not the slightest benefit." He felt Grant's plan was illogical and didn't consider the canal's needs or water supply.

Walsh had designed the canal with four equal-sized locks. Water from one lock would flow into the next, so water was only lost at the last lock. But Grant's changes messed this up. Opening the first lock would not provide enough water for the new, larger second lock. And when the large second lock opened, the smaller third lock couldn't hold all the water, so it would be wasted.

Butler gave the letter to Grant, who then tried to fix the water supply problem. He suggested making the entire canal a reservoir. These plans were dropped. The final plans submitted in April 1907 showed Grant's original layout, with no plan for extra water. Butler's final submission to the Department included most of Grant's changes. The estimated cost for the second section was $596,826, and it was hoped to be finished by March 1908.

Construction Begins

Bids for the second section of the canal were sent out in spring 1907. All the bids were much higher than Grant's estimates. John Riley won the contract in June 1907 but couldn't get the money needed. In January 1908, Riley sold his contract to William Russel, who formed the York Construction Company in April 1908.

Construction on section 2 finally began in April, mostly using Italian workers from Toronto. Some local people complained because they expected more local workers to be hired. There were a few small worker disputes, but they didn't stop construction. Newmarket businesses did get some supply work. Landowners whose properties were flooded were paid about $42,000. Some people claimed that the amount paid was based on political connections, with some landowners getting much more than their land was worth.

Construction started around the time of the 1908 Canadian federal election. The canal helped Ayleworth win his seat, but only by a small number of votes. About $185,000 was spent in 1908, and a similar amount was requested for 1909. Opponents pointed out that the Minister, Graham, had criticized another canal project as wasteful. Now he was supporting the Newmarket canal, which had even less potential traffic and cost twice as much.

Water Supply Problems Continue

By 1905, it was clear the canal project had strong political support. So, the Conservatives changed their attacks to focus on the lack of water. In June 1906, politicians Sam Hughes and Albert Edward Kemp questioned the Minister of Railways and Canals about the water supply. The Minister said there was "an ample supply of water." But Kemp argued there wasn't enough water for even a few boys to swim in.

The Minister stated that the canal would have 30,420 cubic feet (861 m³) of water per hour, and a lock needed 28,000 cubic feet (793 m³) to fill. While this was true for Walsh's original plan, Grant's changes doubled the lock size to 58,000 cubic feet (1,642 m³). This would mean it would take at least two hours to fill a lock.

Because of the constant questions in Parliament, Butler told Grant to measure the water flow carefully. The results, presented in 1909, showed an average flow of 32,400 cubic feet (917 m³) per hour, dropping to 26,700 cubic feet (756 m³) in late summer. This meant the main lock could only operate a few times an hour during floods and wouldn't even cover leakage in summer.

Walsh's plan to use Lake Wilcox couldn't be used because of legal issues. South of Newmarket, there was no other good source of water. Someone in the Ministry suggested pumping water uphill from Lake Simcoe to a reservoir south of Newmarket. The new Minister, Graham, announced this idea, which was met with more laughter.

Grant continued to work on the problem. In June 1909, he suggested installing special seals in the middle of the locks to prevent water leakage. These would sit at the bottom of the lock and be raised using winches. Butler approved these changes, but it was found that the constant changes to the plans led to extra payments to the contractors.

Ongoing Debates

As the huge water supply problem became clear, the project was constantly mocked in the newspapers. One newspaper joked that builders wouldn't need swing bridges because people could just walk across the canal in their rubber boots. Another cartoon showed politicians trying to fill a dry ditch with a hand pump.

Things were no better in the House of Commons of Canada. Haughton Lennox, a politician from the area, strongly opposed the canal. Even Graham, the Minister in charge, joked about it, saying there was "plenty of water in it for all the commerce there will ever be on it."

The opposition launched a full attack on the canal in 1909. The government tried to hide the canal's costs within the larger Trent system budget. But on February 25, Graham was asked to separate the Newmarket costs, which he refused to do.

On March 23, Thomas George Wallace tried to stop the canal by proposing an amendment to cancel it. He called it "a wanton misuse and waste of public money." The debate lasted for hours, with many politicians speaking against the project. The Liberals barely managed to defeat the motion.

After almost losing a motion of no confidence, Prime Minister Laurier asked Mulock for information on everyone involved. Mulock found that many people complaining about the canal, including Lennox, had signed the original request for it. Mulock also suggested they mention the canal's use for pleasure boats, but Laurier never used this idea. A similar fight happened in 1910 when the opposition tried to reduce the Trent budget by the exact amount of the Newmarket work.

As Walsh had predicted, he was blamed for the problems in the debates. This blame came from Butler. Butler quit his job in January 1910. Walsh applied for the chief engineer position, but Butler and Haney worked against him. Walsh then wrote a letter to H.S. Cane in April 1910, explaining the whole situation and blaming Butler. He threatened to go public if Cane didn't help him.

This effort didn't work. Walsh sent another letter to Graham in January 1911, blaming Butler and clearing himself. When Graham tried to hide the letter, Walsh leaked it to Wallace, who read it in Parliament. Wallace then used it to propose another motion of no confidence. The debate lasted for hours, focusing on the Newmarket Canal as an example of wasteful government spending.

Cancellation of the Project

All the debate was for nothing, as Laurier called an election for September 21. The Liberals campaigned on free trade, while the Conservatives focused on the Liberals' high spending. The Newmarket Canal was a key example of an out-of-control government. Aylsworth decided not to run again. The canal was still popular locally, but not enough to save the riding, which the Conservatives won in a close race.

When Robert Borden's Conservative government came to power, Frank Cochrane replaced Graham as Minister of Railways and Canals. Cochrane immediately stopped construction on the canal. He ordered a new report on all ongoing projects. The new chief engineer, W.A. Bowden, reported in January 1912 that about 80% of the main canal work was done, but little dredging of the upper Holland River had happened. He estimated that traffic would be limited to pleasure boats and barges carrying wood. He also said that staffing the locks and bridges would cost $4,000 a year, plus another $4,000 to run the pumping system needed to keep the canal full. Even though most of the work was complete, he estimated they could save $393,000 if the project was abandoned.

Borden signed the report on January 5. Negotiations with the companies involved began right away. The companies received a small payment for cleaning up the sites and were given contracts for other locks on the Trent-Severn. A group of businessmen from Newmarket asked Parliament to complete the canal, but the government ignored their request. The canal was left unfinished. It wasn't until 1924 that more money was provided to clean up the construction sites.

The Holland River did eventually get a canal system, but in a different place and for different reasons. Starting in the 1920s, the Holland Marsh area, west of Newmarket, built two large drainage canals. These are called the north and south canals.

Canal Route

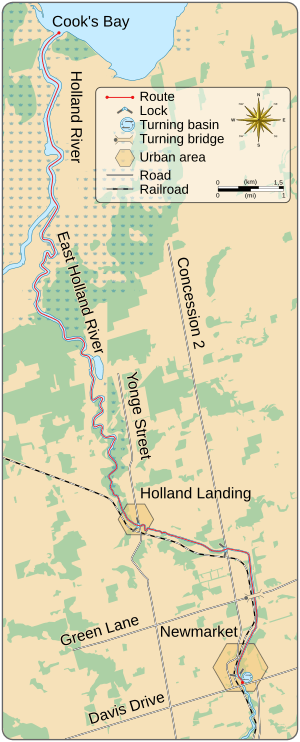

The canal route starts on the eastern part of the Holland River. This part splits off from the western part just south of Cook's Bay. The eastern part flows south through River Drive Park and into Holland Landing. At the southwest corner of town, it turns southeast. After a short distance, it reaches the first lock, which is now under the bridge for "old" Yonge Street.

The river continues southeast for two kilometers to the second lock at Concession 2 (Bayview Avenue). Here, it meets the Rogers Reservoir, which helped store water. At this point, it turns south again for just over a kilometer. Then it turns southwest into Newmarket through the third lock, which is just north of the canal's end.

The canal ended in a turning basin on the north side of Davis Drive in Newmarket. This was the northern end of the downtown area. The Holland River continues south from this point, with Main Street running next to it. The city grew along this north-south line. Fairy Lake, south of downtown, is 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) south of the turning basin.

Most of the canal route is still there. The southern part is now next to the Nokiidaa Bicycle Trail, which goes from Newmarket to Holland Landing. The turning basin was filled in during the 1980s. It is now part of the parking lot for the Tannery Mall and the Newmarket GO Station.

The single-lane swing bridge over Green Lane was used until 2002. Then, a much larger four-lane bridge replaced it. The original bridge structure was later replaced by a footbridge. The original swing mechanism was moved to one end of the new footbridge. Lock #1 in Holland Landing was used as the foundation for a new Yonge Street bridge. Lock #2 was used for a bridge on 2nd Concession Road. Lock #3 in Newmarket now carries the bike trail over the river.

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |