Oberlin–Wellington Rescue facts for kids

The Oberlin–Wellington Rescue was an important event in 1858. It happened in Ohio and was a big part of the fight against slavery in the United States. This event became very famous, partly because news could travel fast using the new telegraph. It was one of many events that led to the American Civil War.

Here's what happened: A man named John Price, who had escaped slavery, was arrested in Oberlin, Ohio. He was arrested because of a law called the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law said that escaped slaves had to be returned to their owners. The U.S. marshal (a type of police officer for the federal government) knew that people in Oberlin strongly opposed slavery. So, to avoid trouble, he took Price to Wellington, Ohio, to catch a train.

But people from Oberlin followed them. They rescued Price from the marshal and took him back to Oberlin. From there, Price traveled on the Underground Railroad to Canada, where he could be truly free.

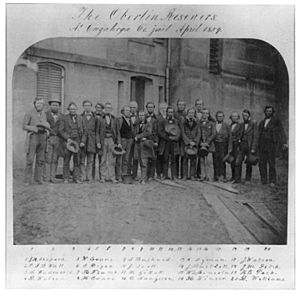

Later, 37 people who helped in the rescue were accused of breaking the law. However, after talks between the state and federal governments, only two people went to trial. This case got a lot of attention across the country. The people on trial spoke strongly against the Fugitive Slave Law. Because of this rescue and the continued actions of those involved, the issue of slavery stayed a major topic in national discussions.

Contents

Early Actions Against Slavery

Even before the Oberlin–Wellington Rescue, people in Oberlin were known for helping escaped slaves. For example, in 1841, a group of strong abolitionists from Oberlin helped free two captured escaped slaves from the Lorain County jail. They even used saws and axes to do it!

The Rescue Story

On September 13, 1858, a man named John Price, who had escaped slavery from Maysville, Kentucky, was arrested in Oberlin, Ohio. A U.S. marshal arrested him under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law meant the government had to help slave owners get their escaped slaves back. Local officials also had to help.

The marshal knew that many people in Oberlin were abolitionists. This meant they were against slavery. Oberlin and its college were famous for their strong anti-slavery views. To avoid problems, the marshal quickly took Price to nearby Wellington, Ohio. He planned to put Price on a train to Columbus, Ohio, and then send him back to his owner in Kentucky.

As soon as people in Oberlin heard about the arrest, a group of men rushed to Wellington. They met up with people in Wellington who also wanted to help Price. They tried to free him, but the marshal and his helpers hid in a local hotel. After peaceful talks didn't work, the rescuers stormed the hotel. They found Price in the attic.

The group immediately took Price back to Oberlin. They hid him in the home of James Harris Fairchild, who would later become the president of Oberlin College. A short time later, they helped Price travel to Canada. Canada was the end of the Underground Railroad, and there was no slavery there, so escaped slaves were safe. We don't know what happened to John Price after he reached Canada.

The Court Case

A federal grand jury (a group of citizens who decide if there's enough evidence for a trial) accused 37 people who helped free John Price. Professor Henry E. Peck was one of them. Twelve of the people accused were free black men. One of these was Charles Henry Langston, who made sure Price went to Canada and not back to the authorities. Charles and his brother John Mercer Langston both graduated from Oberlin College. They led the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in 1858. Both brothers were active in politics their whole lives. Charles worked in Kansas, and John became a leader in state and national politics. In 1888, John was the first African-American elected to the U.S. Congress from Virginia.

People in Ohio felt very strongly about Price's rescue. When the federal grand jury accused the rescuers, state officials arrested the federal marshal and his helpers. After some discussions, the state agreed to release the marshal. In return, federal officials agreed to drop charges against 35 of the accused rescuers.

Only two people, Simeon M. Bushnell (a white man) and Charles H. Langston, went to trial. Four well-known local lawyers defended them. The people chosen for the jury were all known to be Democrats. After they found Bushnell guilty, the same jury was asked to try Langston. Langston argued that they could not be fair to him.

Langston gave a powerful speech in court. He spoke strongly for ending slavery and for justice for black people. He ended his speech with these words:

But I stand up here to say, that if for doing what I did on that day at Wellington, I am to go to jail six months, and pay a fine of a thousand dollars, according to the Fugitive Slave Law, and such is the protection the laws of this country afford me, I must take upon my self the responsibility of self-protection; and when I come to be claimed by some perjured wretch as his slave, I shall never be taken into slavery. And as in that trying hour I would have others do to me, as I would call upon my friends to help me; as I would call upon you, your Honor, to help me; as I would call upon you [to the District-Attorney], to help me; and upon you [to Judge Bliss], and upon you [to his counsel], so help me GOD! I stand here to say that I will do all I can, for any man thus seized and help, though the inevitable penalty of six months imprisonment and one thousand dollars fine for each offense hangs over me! We have a common humanity. You would do so; your manhood would require it; and no matter what the laws might me, you would honor yourself for doing it; your friends would honor you for doing it; your children to all generations would honor you for doing it; and every good and honest man would say, you had done right!

—Great and prolonged applause, in spite of the efforts of the Court and the Marshal to silence it.

The jury also found Langston guilty. The judge gave them light sentences: Bushnell got 60 days in jail, and Langston got 20 days.

The Appeal

Bushnell and Langston asked the Ohio Supreme Court to review their case. They argued that the federal court didn't have the power to arrest and try them. They said the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was against the Constitution. The Ohio Supreme Court decided that the law was constitutional by a vote of three to two. Chief Justice Joseph Rockwell Swan personally disliked slavery. But he wrote that his job as a judge meant he had to agree that a law passed by the United States Congress was the highest law in the land. This is known as the Supremacy Clause.

Many abolitionists in Ohio were very angry about this decision. More than 10,000 people gathered at a rally in Cleveland to protest the court's decisions. Important Republican leaders like Governor Salmon P. Chase and Joshua Giddings were there. John Mercer Langston was the only black speaker that day. Because of his decision, Chief Justice Swan lost his chance to be re-elected. His political career in Ohio was over.

What Happened Next

Over time, disagreements about slavery and how to understand the Constitution led to the start of the Civil War. The Oberlin–Wellington Rescue was important because it got a lot of national attention. It also happened in an area of Ohio famous for its Underground Railroad activity.

The people who took part in the rescue continued to be active in Ohio and national politics. In 1859, those who attended the Ohio Republican convention successfully added a goal to their party's plan: to get rid of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The rescue and the ongoing actions of its participants kept the issue of slavery in the national discussion.

Two people from the Oberlin–Wellington Rescue, Lewis Sheridan Leary and John A. Copeland, along with Oberlin resident Shields Green, later joined John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859. Leary was killed during the attack. Copeland and Green were captured and put on trial with John Brown. They were found guilty of treason and were executed on December 16, 1859, two weeks after John Brown.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |