Oboe (navigation) facts for kids

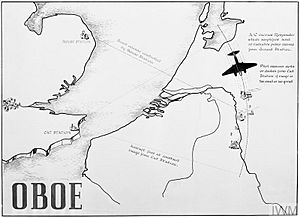

Oboe was a clever British system that helped planes drop bombs very accurately, even in bad weather or at night. It used special radar and radio signals. Two ground stations, far apart, would track an airplane. Before a mission, two imaginary circles were drawn, one around each station. These circles would meet exactly where the bombs needed to fall.

The people operating the ground stations would use their radar, helped by a device on the plane called a radio transponder, to guide the bomber. They would tell the pilot to fly along one of the circles. When the plane reached the spot where the two circles crossed, the bombs were released.

Oboe was created in 1942 by the Telecommunications Research Establishment in Malvern, Worcestershire. It worked closely with No. 109 Squadron RAF. By December 1942, the system was ready. Oboe was first used in a big way in March 1943. It helped mark the Krupp Works in Essen, Germany, for an attack. That month, Oboe was used with great success to mark targets in the German industrial area called the Battle of the Ruhr. It also helped with attacks on Cologne. Until November 1943, Oboe worked well for targets within its range of about 250 miles (400 km).

In December 1943, RAF Bomber Command started an important campaign called the Battle of Berlin. But Berlin was too far away for Oboe to reach, even for planes flying very high. So, planes had to rely on other navigation systems. The attacks on Berlin over the next four months were not very successful.

By late March 1944, Bomber Command was asked to help prepare for the invasion of Europe. These missions to northern France showed how valuable Oboe was again. It could precisely guide planes to drop markers or bombs, no matter the weather or if the target was visible. Oboe was the most accurate bombing system used during the war.

Contents

How Oboe Was Developed

To know exactly where you are on the ground, you need at least two pieces of information. This could be two angles (like in triangulation) or two distances (trilateration). Before World War II, people were always trying to use radio signals for these measurements.

The Germans had early systems like Lorenz beam and X-Gerät. These used two narrow radio beams that crossed in the sky to show a target. Later, during The Blitz, they used Y-Gerät. This combined one beam with a distance measurement from a transponder. The problem was that these systems only worked within their narrow beams. They weren't good for general navigation.

The British Gee system was more useful. It used two timed radio signals. A navigator on the bomber could use these to figure out their location using trilateration. Gee worked anywhere within sight of the transmitter stations in the UK, usually up to about 500 km (310 miles). However, Gee's display was small, which limited its accuracy. It was good for general navigation but not for hitting a small target precisely.

To make Gee more accurate, you'd need a much bigger display. But in those days, large cathode ray tube (CRT) displays were very expensive and too big for many planes.

The Oboe Idea

The idea of putting the display on the ground instead of in the plane was clear. Alec Reeves first suggested it in 1940. Then, Francis Jones helped present the idea in 1941.

The main idea was to have two ground stations send out radio signals. The airplane would have special devices called transponders. These transponders would receive the signals and immediately send them back. By timing how long it took for the signal to go from the ground station to the plane and back, the distance to the plane could be figured out. This was like radar, but the transponder made the return signal much stronger, which helped with accuracy.

A challenge was how to use these distance measurements to guide a bomber. With one beam, like the German Y-Gerät, the plane just flew along the beam. But with two distance measurements, there wasn't a natural path. You could call the two distances to a plotting room, draw arcs on a map, and find where they crossed. But this took too long, and the plane would have moved.

Oboe found a simple solution. Before a mission, a path was chosen. This path was a circle around one of the ground stations, called "Cat." This circle passed right through the target. The plane would fly towards the target, and an operator at the Cat station would tell the pilot if they were too close or too far from the station. This kept the plane flying exactly along the chosen circle.

As the plane flew along this circle towards the target, the second station, called "Mouse," also measured its distance to the plane. When the plane got close to the target, the Mouse station would send a "heads up" signal to the bomb aimer. Then, at the exact right moment, it would send a signal to drop the bombs. This way, the stations didn't need to compare measurements or do complex math. They just used simple distance readings and sent separate instructions to the plane.

Instead of talking, the ground stations sent signals using Morse code dots or dashes. If the plane was too close to Cat, the operator sent dots. If too far, they sent dashes. When the plane was at the perfect distance, the dots and dashes would blend into a steady tone. The stations also sent letters (X, Y, Z) to tell the pilot how far they were from the correct path. Mouse sent signals like S, A, B, C, D to show how close the plane was to the bomb release point.

Testing and Improvements

One problem with Oboe was that each ground station could only guide one plane at a time. Other systems like Gee could be used by many planes at once. So, Oboe was used for "pathfinders"—special planes that would drop flares to mark targets for other bombers to follow.

Another concern was that the plane had to fly straight and level along a curved path. Also, the British had easily jammed German systems. They expected the Germans to do the same to Oboe.

Despite some doubts, A.P. Rowe ordered Oboe's development to continue. They worked on two versions: one using the older 1.5-meter radio waves and a new one using 10-cm microwaves. The microwave version would be much more accurate and harder for the Germans to jam.

Two stations were set up in England: one in Dover (Walmer) and another in Cromer (RAF Trimingham). In tests in September 1941, a plane flying 130 km (80 miles) from Dover showed an accuracy of 50 meters (164 feet). This was much better than any other bombing method at the time. In a demonstration in July 1942, Oboe showed a real-world accuracy of 65 meters (213 feet). In contrast, other bombing methods in 1942 were accurate only to about 1,500 yards (1,370 meters).

Oboe was first used in combat tests in December 1941 by Short Stirling bombers attacking Brest. These planes couldn't fly very high, so they were limited to short-range attacks where they could still "see" the signals from the UK.

There was a big discussion in Bomber Command about using "pathfinders." These were special planes and crews that would find targets and mark them with flares. It was decided that the fast Mosquito planes, which could fly very high, would be equipped with Oboe to be pathfinders.

Oboe in Action

The first combat missions with Oboe over Germany happened on December 20-21, 1942. Six Oboe-equipped Mosquitoes were sent to bomb a power station in the Netherlands. Three of the systems failed, but the other three planes dropped their bombs correctly. A photo mission the next day showed that nine bomb craters were grouped closely together, though about 2 km (1.2 miles) from the target. More tests were done in December and January.

At first, the Germans thought these small attacks were just annoying raids. But they soon noticed something strange: planes were dropping only a few bombs, often through thick clouds, and 80-90% of them were hitting important targets like blast furnaces or power stations. The Germans realized the British were using a new, very accurate bombing system.

The early tests over Europe sometimes missed the target more than expected. But it became clear there was a pattern to the misses. This was because of differences in how maps were made in the UK and Europe. The Germans themselves had helped solve this problem before the war by sharing map calibration data. Using this, the British could correct the inaccuracies quickly.

By late spring 1943, Bomber Command crews had practiced enough to start major operations. Arthur Harris began a series of raids called the Battle of the Ruhr. The first raid on Essen in March didn't go well, but later raids, like the one on the Krupp factory, were more successful. By May, the technique was perfected. Large raids with 500 to 800 bombers became very successful. For example, a raid on Dortmund in May stopped production at the Hoesch steelworks. A raid on Krupps in July caused "complete stoppage of production." Analysis showed that the number of bombs hitting their targets doubled compared to before Oboe.

German Countermeasures

German radar operators could easily spot Oboe missions. The planes would start far from the target and then fly in a curved path. This path was called "Boomerang" by the Germans. Even though they knew these planes were coming, it was very hard to intercept the high-flying, fast aircraft.

It took the Germans over a year to understand how Oboe worked. The first attempt to jam Oboe happened in August 1943 during an attack on a steelworks in Essen. A German system tried to send false dot and dash signals on the 1.5-meter band. They hoped this would confuse the pilot.

But the Germans didn't know that Oboe had already moved to the microwave 10-cm Oboe Mk. II version. The British kept broadcasting the older signals as a trick. The Germans couldn't figure out why their jamming wasn't working until July 1944. By then, the RAF had already introduced Oboe Mk. III, which was even harder to jam. Mk. III also allowed up to four planes to use the same stations and allowed different flight paths.

Later War Use

By this time, the Battle of the Ruhr was over. Most of the RAF's bombing efforts were on targets deeper inside Germany, too far for Oboe. So, another system called H2S became more important. However, after the D-Day invasions, new Oboe stations could be set up in Europe.

Late in the war, Oboe helped with food drops to the Dutch people who were still under German occupation. This was part of Operation Manna. Drop points were arranged with the Dutch Resistance, and food packages were dropped within about 30 meters (100 feet) of the target using Oboe.

Technical Details

Oboe used two ground stations in England. These stations sent a signal to a Mosquito Pathfinder bomber. The Mosquito had a radio transponder that sent the signals back. By measuring the time it took for the signal to go there and back, each ground station could figure out its distance to the bomber.

Each Oboe station used this distance measurement to define a circle. The point where the two circles from the "Cat" and "Mouse" stations met was the target. The Mosquito flew along the circle defined by the "Cat" station. It dropped its bombs or flares when it reached the intersection point with the "Mouse" station's circle. There was a network of Oboe stations across southern England, and any of them could be used as a Cat or a Mouse.

The Mark I Oboe system used radio frequencies of 200 MHz (1.5 meters). The two stations sent out quick radio pulses. These pulses could be short or long, so the plane received them as Morse code dots or dashes. The Cat station sent continuous dots if the plane was too close and continuous dashes if it was too far. The pilot would use these signals to correct their course.

The Mouse station had a special computer called "Micestro." This computer figured out the exact moment to tell the plane to release its bombs. The Mouse station would send five dots and a dash to signal the bomb release.

The basic idea for Oboe came from Alec Reeves of Standard Telephones and Cables Ltd. It was developed with Frank Jones of the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE). Dr. Denis Stops was also part of the team. He helped develop the systems on the aircraft. Dr. Stops once said that a side benefit of Oboe was that the Germans often didn't know what the British were planning to bomb.

Similar Systems

The Germans created a system similar to Oboe called Egon. They used it for bombing on the Eastern Front. It used two modified Freya radars as the Cat and Mouse stations. These were about 150 km (93 miles) apart. The plane had a special device to respond to them. An operator at each station would tell the pilot how to correct their course by radio.

Oboe had one main limitation: only one plane could use it at a time. To fix this, the British developed a new system called "GEE-H" (or "G-H"). It used the same basic ideas but allowed more than one plane to use the two ground stations. Each plane's signal had a unique timing pattern. This allowed the ground stations to handle up to about 80 planes at once.

The name "GEE-H" can be confusing because it was a change to Oboe. It was called GEE-H because it used similar technology to the original Gee system. The "H" meant it used the "twin-range" or 'H' principle of measuring distance from two ground stations. It was almost as accurate as Oboe.

See also

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |