Octavia E. Butler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Octavia E. Butler

|

|

|---|---|

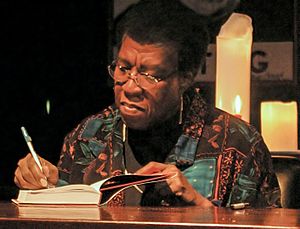

Butler signing a copy of Fledgling in 2005

|

|

| Born | Octavia Estelle Butler June 22, 1947 Pasadena, California, U.S. |

| Died | February 24, 2006 (aged 58) Lake Forest Park, Washington, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Education | Pasadena City College (AA) California State University, Los Angeles |

| Period | 1970–2006 |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Notable awards | MacArthur Fellow Hugo Award Nebula Award See list |

| Signature | |

Octavia Estelle Butler (born June 22, 1947 – died February 24, 2006) was an amazing American science fiction author. She won many important awards for her writing, like the Hugo and Nebula awards. In 1995, she made history by becoming the first science fiction writer to receive a special award called a MacArthur Fellowship.

Born in Pasadena, California, Octavia Butler was raised by her mother after her father passed away. She was a very shy child, but she found comfort and adventure in books. She loved reading fantasy and started writing her own science fiction stories when she was a teenager. She went to college during a time when the Black Power movement was important. She also joined a writing group where she was encouraged to attend a special workshop for science fiction writers.

Soon, she started selling her stories. By the late 1970s, she was successful enough to become a full-time writer. Her books and short stories became very popular and won many awards. She also taught writing workshops and later moved to Washington. Octavia Butler passed away at 58 years old. Her writings and notes are now kept at the Huntington Library in Southern California.

Contents

Early Life and Discovering Writing

Octavia Estelle Butler was born in Pasadena, California. She was the only child of Octavia Margaret Guy, who worked as a housemaid, and Laurice James Butler, a shoeshiner. Octavia's father died when she was only seven years old. Her mother and grandmother raised her in a strict Baptist home.

Growing up in Pasadena, Octavia saw many different cultures and people. However, there was still racial segregation at that time. This meant that Black people and white people were often kept separate. Octavia would go with her mother to her cleaning jobs, where they had to enter white people's homes through the back doors. Her mother was not always treated well by her employers.

From a young age, Octavia was very shy. It was hard for her to make friends. She also had a mild form of dyslexia, which made schoolwork difficult. Because of this, other kids sometimes picked on her. She felt like she was "ugly and stupid, clumsy, and socially hopeless." So, she spent a lot of time reading at the Pasadena Central Library. She also wrote many stories in her "big pink notebook."

At first, she loved fairy tales and horse stories. But soon, she discovered science fiction magazines like Amazing Stories and Galaxy Science Fiction. She started reading stories by authors like John Brunner and Theodore Sturgeon.

When she was 10, Octavia asked her mother for a Remington typewriter. She used it to "peck" out her stories with two fingers. At 12, she watched a movie called Devil Girl from Mars (1954). She thought she could write a much better story! This idea became the start of her Patternist novels. At 13, her aunt Hazel told her that "Negroes can't be writers." This made Octavia unsure for a moment, but she kept going. She even asked her junior high science teacher to type her first story to send to a magazine.

After finishing John Muir High School in 1965, Octavia worked during the day and went to Pasadena City College (PCC) at night. There, she won a short-story contest and earned her first $15 as a writer. She also got the idea for her famous novel Kindred. A classmate in the Black Power Movement criticized older generations of African Americans. Octavia wanted to write a story that showed why people acted the way they did in the past. She wanted to show that their actions were often a brave way to survive. In 1968, she earned her associate of arts degree in history from PCC.

Becoming a Successful Writer

Octavia's mother wanted her to be a secretary for a steady job. But Octavia wanted to write. She took temporary jobs that didn't demand too much, so she could wake up early, sometimes at two or three in the morning, to write. It took a while for her to find success. She tried to write like the white, male science fiction authors she read. She took writing classes at UCLA Extension.

At a special workshop for minority writers, her writing impressed a famous science fiction writer named Harlan Ellison. He told her to attend the six-week Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop. There, she met Samuel R. Delany, who became a good friend. She also sold her first two stories: "Childfinder" and ""Crossover"."

For the next five years, Octavia worked on her Patternist series novels. These included Patternmaster (1976), Mind of My Mind (1977), and Survivor (1978). By 1978, she was finally able to stop working temporary jobs and write full-time! She then wrote Kindred (1979), which is a very popular standalone novel. She finished her Patternist series with Wild Seed (1980) and Clay's Ark (1984).

Octavia Butler became very well known starting in 1984. Her short story "Speech Sounds" won the Hugo Award. The next year, her story Bloodchild won the Hugo Award, the Locus Award, and the Science Fiction Chronicle Reader Award. She even traveled to the Amazon rainforest and the Andes mountains to research her next series, the Xenogenesis trilogy. These books were Dawn (1987), Adulthood Rites (1988), and Imago (1989). They were later collected as Lilith's Brood.

In the 1990s, Octavia wrote the novels that made her even more famous: Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). In 1995, she received the amazing John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation fellowship, which came with a large prize of $295,000. This was a huge honor for a science fiction writer.

After her mother passed away in 1999, Octavia moved to Lake Forest Park, Washington. The Parable of the Talents won the Nebula Award for Best Science Novel. She had planned to write four more books in the Parable series. However, she found the research and writing for these books very difficult and sad. So, she decided to write something "lightweight" and "fun" instead. This became her last book, the science fiction vampire novel Fledgling (2005).

Later Years and Legacy

In her last years, Octavia Butler kept writing and teaching at the Clarion Science Fiction Writers' Workshop.

After a period where it was hard for her to write, she published the short stories "Amnesty" (2003) and "The Book of Martha" (2003). Her last standalone novel, Fledgling, came out in 2005.

In 2005, she was honored by being added to Chicago State University's International Black Writers Hall of Fame.

Octavia Butler passed away at her home in Lake Forest Park, Washington, on February 24, 2006, when she was 58 years old. News reports at the time said she died from a stroke.

Octavia had a long relationship with the Huntington Library. In her will, she left all her papers to the library. This huge collection includes her handwritten stories, letters, school papers, notebooks, and photos. It became available for scholars and researchers in 2010.

Important Ideas in Her Stories

Thinking About How People Treat Each Other

In her interviews and writings, Octavia Butler often talked about how humans tend to create groups where some people are in charge and others are not. She believed this "pecking order" thinking can lead to problems like racism, sexism, and violence. She felt that if we don't control this, it could even destroy humanity.

Her stories often show how strong people try to control weaker ones. But her main characters are usually different or unique. They challenge the powerful and try to bring about change. Octavia's stories are like fables that explore how we can solve the problems that make humans hurt each other.

Heroes Who Keep Going

Octavia Butler's main characters are often people who don't have much power. But they are strong and keep going, even when things are very hard. They learn to adapt and change to survive. Even if they have special abilities, these characters face huge challenges. They go through physical, mental, and emotional pain. They do this to have some control over their lives and to stop humanity from destroying itself. In many stories, their brave actions lead to understanding and even love. They find ways to work with those in power. Octavia's focus on these characters shows how minorities have been treated in history. It also shows how one person's determination can bring important change.

Science Fiction and African American Culture

Octavia E. Butler is known for mixing science fiction with ideas from African American spiritualism.

Her work is often connected to Afrofuturism. This is a term for science fiction that explores African American themes and concerns, often looking at technology and the future. Some people point out that while Octavia's main characters are often Black, the communities they create in her stories are usually made up of many different ethnic groups and even different species.

Who Influenced Octavia Butler

Octavia Butler said that her working-class mother's struggles were a big influence on her writing. Her mother didn't have much formal education. But she made sure Octavia had books and magazines that her white employers threw away. She wanted Octavia to learn.

Her mother also encouraged her to write. She bought Octavia her first typewriter when she was 10. She casually said that maybe one day Octavia could be a writer, which made Octavia realize it was possible to earn a living from writing. Years later, her mother even used money she saved for dental work to help Octavia pay for a scholarship to the Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop. This is where Octavia sold her first two stories.

Another important person in Octavia's life was the American writer Harlan Ellison. He was a teacher at a writing workshop. He gave Octavia her first honest and helpful feedback on her writing. He was impressed by her work and suggested she go to the Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop. He even gave her $100 to help with the application fee. Over the years, Harlan Ellison became a close friend and mentor to Octavia.

Octavia Butler's Impact

Octavia Butler has had a huge impact on science fiction, especially for people of color. In 2015, Adrienne Maree Brown and Walidah Imarisha put together a book called Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements. It's a collection of stories and essays inspired by Butler's work. Toshi Reagon even turned Parable of the Sower into an opera. In 2020, Adrienne Maree Brown and Toshi Reagon started a podcast called Octavia's Parables.

Her Unique Point of View

Octavia Butler started reading science fiction when she was young. But she soon noticed that the genre didn't show much variety in terms of race or social class. It also didn't have many strong female main characters. She decided to change that. As she said, she wanted to "write myself in." This meant writing from the perspective of an African-American woman. Her stories often feature a Black woman who is different from the main group. This difference helps her change the future of her society.

Who Read Her Books

Publishers and critics called Octavia Butler's work science fiction. She loved the genre, calling it "potentially the freest genre in existence." But she didn't want to be known only as a "genre writer." Her stories attracted readers from many different backgrounds. She said she had three main groups of loyal readers: Black readers, science fiction fans, and feminists.

Awards and Honors

- 1980: Creative Arts Award, L.A. YWCA

- 1984: Hugo Award for Best Short Story – "Speech Sounds"

- 1984: Nebula Award for Best Novelette – "Bloodchild"

- 1985: Locus Award for Best Novelette – "Bloodchild"

- 1985: Hugo Award for Best Novelette – "Bloodchild"

- 1985: Science Fiction Chronicle Award for Best Novelette – "Bloodchild"

- 1988: Science Fiction Chronicle Award for Best Novelette – "The Evening and the Morning and the Night"

- 1995: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation "Genius" Grant

- 1995: Bloodchild a New York Times Notable Book

- 1997: Honorary Degree in Humane Letters, from Kenyon College

- 1998: Publishers Weekly Best '98 Books – Parable of the Talents

- 1998: James Tiptree Jr. Award Honor List– Parable of the Talents

- 1999: Los Angeles Times Bestseller – Parable of the Talents

- 1999: Nebula Award for Best Novel – Parable of the Talents

- 2001: Arthur C. Clarke Award Shortlist – Parable of the Talents

- 2000: Lifetime Achievement Award in Writing from the PEN American Center

- 2005: Langston Hughes Medal of The City College

- 2010: Inducted by the Science Fiction Hall of Fame

- 2012: Solstice Award

- 2018: The International Astronomical Union named a mountain on Charon (a moon of Pluto) Butler Mons to honor the author.

- 2018: Google featured her in a Google Doodle in the United States on June 22, 2018, which would have been Butler's 71st birthday.

- 2019: Asteroid 7052 Octaviabutler, discovered in 1988, was named in her memory. The official naming citation was published on August 27, 2019.

- 2019: Los Angeles Public Library opened the Octavia Lab, a special do-it-yourself space named in Butler's honor.

- 2020: Ignyte Award for Best Comics Team for a graphic novel version of Parable of the Sower.

- 2021: Named as one of the women inducted to the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

- 2021: NASA named the landing site of the Perseverance rover on Mars the "Octavia E. Butler Landing" in her honor.

- 2022: A school Octavia Butler attended changed its name to Octavia E. Butler Magnet.

- 2023: In February 2023, a bookstore named Octavia's Bookshelf opened in Pasadena, California.

Memorial Scholarships

In 2006, the Carl Brandon Society created the Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship. This scholarship helps writers of color attend the annual Clarion West Writers Workshop and Clarion Writers' Workshop. These are the workshops where Octavia Butler got her start. The first scholarships were given out in 2007.

In March 2019, Octavia Butler's old college, Pasadena City College, announced its own Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship. This scholarship is for students in a special program who plan to transfer to a four-year university.

Selected Works

Series

Patternist series

- Patternmaster (1976)

- Mind of My Mind (1977)

- Survivor (1978)

- Wild Seed (1980)

- Clay's Ark (1984)

- Seed to Harvest (2007; a collection of some books from the series)

Xenogenesis series

- Dawn (1987)

- Adulthood Rites (1988)

- Imago (1989)

- Xenogenesis (1989) (a collection of Dawn, Adulthood Rites, & Imago)

- Lilith's Brood (2000) (another collection of Dawn, Adulthood Rites, & Imago)

Parable series (also called the Earthseed series)

- Parable of the Sower (1993)

- Parable of the Talents (1998)

Standalone Novels

- Kindred (1979)

- Fledgling (2005)

Short Story Collections

- Bloodchild and Other Stories (1995; updated in 2005 to include "Amnesty" and "The Book of Martha")

- Unexpected Stories (2014, includes "A Necessary Being" and "Childfinder")

See also

In Spanish: Octavia E. Butler para niños

In Spanish: Octavia E. Butler para niños

- Women in speculative fiction

- Afrofuturism

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |