Ogyū Sorai facts for kids

- In this Japanese name, the family name is Ogyū.

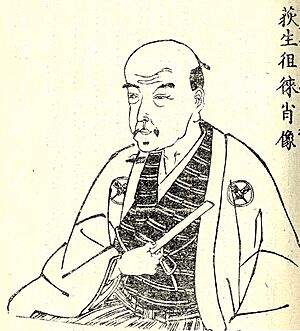

Ogyū Sorai (荻生 徂徠) (born March 21, 1666, in Edo, Japan – died February 28, 1728, in Edo) was an important Japanese philosopher. He often used the pen name Butsu Sorai in his writings. Many people say he was the most influential Confucian scholar during the Edo period in Japan.

Sorai mostly studied how the ideas of Confucius could help the government and improve society. At that time, Japan faced problems with its government and economy. Old ways of doing things were not working well. Sorai believed that some teachings, like "The Way," were used to excuse these problems.

Sorai did not agree with the common Confucian ideas of his time, known as Song Confucianism. Instead, he looked back at much older writings. He thought it was important for people to show their feelings. Because of this, he worked to make Chinese literature more popular in Japan. Sorai had many followers, and his ideas led to the "Sorai school," which became very important in Japanese Confucian studies.

Contents

Life of Ogyū Sorai

Sorai was the second son of a samurai, who was a personal physician to Tokugawa Tsunayoshi. Tsunayoshi later became the fifth shogun, a powerful military ruler of Japan.

Sorai first studied the ideas of Zhu Xi, a famous Song Confucian scholar. By 1690, Sorai became a private teacher of Chinese classic books. In 1696, he started working for Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu, a high-ranking advisor to Shogun Tsunayoshi.

After Tsunayoshi died in 1709, Sorai stopped following Zhu Xi's teachings. He began to create his own philosophy and started his own school of thought. Sorai is also known for creating kō shōgi, which is an unusual type of chess.

Ogyū Sorai's Teachings

Sorai wrote many important books where he pointed out what he saw as two main problems with Song Confucianism.

First, he felt that the government system of the time was in trouble. Sorai believed that simply trying to be a good person was not enough to fix the political problems. He argued that ancient Chinese kings were not just focused on being moral, but also on how to govern well.

Second, Sorai thought that Song Confucianism focused too much on strict morality. He believed it tried to stop human nature, which he saw as being based on emotions. He felt that these were not weaknesses of Confucianism itself. Instead, he thought Song Confucian scholars had misunderstood the old classic books, like the Four Books and the Five Classics. He said they "did not know the old words."

Sorai studied ancient writings to find more accurate knowledge. He believed that understanding history was the best way to gain knowledge. For him, these old works were the best source, even though the world was always changing. Sorai thought that learning philosophy should start with studying language. He was greatly influenced by a movement from the Ming dynasty in China. This movement looked at the Qin dynasty and Han dynasty as models for good writing, and the Tang Dynasty for good poetry.

Sorai's school introduced a book called Selections of Tang Poetry to Japan, and it became very popular. This book was edited by Li Panlong, who helped start the Ancient Rhetoric school in China. Because of this, Sorai's school is also known as the Ancient Rhetoric (kobunji) school today. Sorai's school saw Selections of Tang Poetry as a way to understand the Five Classics. This was different from other Confucian schools. Sorai also criticized other Japanese Confucian scholars, like Hayashi Razan, for relying too much on Song Confucian ideas.

Sorai also disagreed with other parts of Song Confucianism. He believed that "The Way" was not a fixed rule of the universe. Instead, he thought it was something created by people, specifically the ancient wise leaders. These leaders described "The Way" through rites (rei) and music (gaku). Rites helped create social order, and music gave inspiration to the heart. This allowed human emotions to flow freely, which was different from the strict moral ideas of Song Confucianism. Sorai wanted people to be enriched by music and poetry. He taught that literature was important for human expression. As a result, Chinese writing became very popular in Japan, and many great writers of Chinese poetry and prose followed his ideas.

Sorai supported the samurai class. He believed that while other old groups were struggling, the samurai could solve problems using a system of rewards and punishments. Sorai also saw problems with the merchant class, accusing them of working together to control prices. However, he did not support the lower classes studying Confucian classics. He once said, "What possible value can there be for the common people to overreach their proper station in life and study such books?"

Master Sorai's Teachings

Master Sorai's Teachings is a book that records Sorai's ideas and his discussions with his students. His students put the book together, including their questions and his answers. The book was published in 1724, but it was likely written around 1720. In this book, Sorai wrote that literature is not just for teaching morals or how to govern. Instead, it helps human emotions flow. From this flow of emotions, answers to moral and government questions can be found. Sorai wanted to make the Tokugawa shogunate's power stronger.

Criticisms of Sorai

Some scholars did not agree with Sorai's work and thought his teachings were not practical. Goi Ranshū believed that Sorai wanted to be better than Itō Jinsai, another leading Confucian scholar. Goi thought Sorai took Itō's ideas to an extreme level. Goi felt that if people followed Sorai's teachings, it would harm moral philosophy.

Another scholar who criticized Sorai was Nakai Chikuzan. He knew about Goi's opposition to Sorai. Goi wrote his criticisms of Sorai in an essay called Hi-Butsu hen. This essay was written in the 1730s but was not published until 1766. Chikuzan and his brother edited the published essay. Nakai later wrote his own strong response to Sorai's ideas in his work Hi-Chō (1785). In this book, he disagreed with the idea that people could not improve themselves through moral choices. He also said that individuals could decide if outside ideas and actions were true or fair. He felt that denying these morals would leave only "rites and rules" to follow.

Works by Ogyū Sorai

- Regulations for Study (Gakusoku, 1715)

- Distinguishing the Way (Bendō, 1717)

- Master Sorai's Teachings (Sorai sensei tōmonsho, 1724)

- Najita, Tetsuo. (1998). Visions of Virtue in Tokugawa Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN: 0-8248-1991-8

- Shirane, Haruo. (2006). Early Modern Japanese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN: 0-231-10990-3

- Totman, Conrad. (1982). Japan Before Perry. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN: 0-520-04134-8

- Tucker, J., ed. (2006). Ogyu Sorai’s Philosophical Masterworks: The Bendo And Benmei (Asian Interactions and Comparisons). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN: 978-0-824-82951-3

- Yamashita, Samuel Hideo. (1994). Master Sorai's Responsals: An Annotated Translation of Sorai Sensei Tōmonsho. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN: 9780824815707

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ogyū Sorai para niños

In Spanish: Ogyū Sorai para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |