Operation Peter Pan facts for kids

| Part of the Golden exile | |

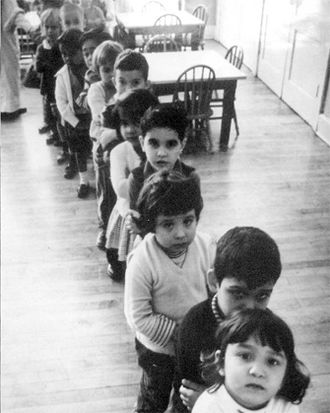

Cuban children waiting in line to emigrate.

|

|

| Date | 1960–1962 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Cause | Education in Cuba

|

| Outcome | 14,000 unaccompanied minors arrive in the United States |

Operation Peter Pan (also known as Operación Pedro Pan) was a secret program. It moved over 14,000 Cuban children, aged 6 to 18, to the United States. These children traveled alone between 1960 and 1962. Their parents sent them because they feared that Fidel Castro and the Communist government would take away their children. They worried the government would place them in special schools. These schools would teach them only communist ideas. This fear was often called the Patria Potestad.

The program had two main parts. First, it helped many Cuban children fly to the United States. Miami was a very common arrival city. Second, it set up programs to care for them once they arrived. Father Bryan O. Walsh of the Catholic Welfare Bureau led both parts. This operation was the largest movement of child refugees in the Western Hemisphere at that time. It was kept secret. People feared it would be seen as a political action against Castro.

Contents

Why Operation Peter Pan Started

After the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 changed Cuba. After October 1960, the government took control of many businesses. This caused the first group of Cubans to leave for the United States. These were often wealthy or upper-middle-class people. They did not support the old government. But their businesses could not work with the new government's plans. Most of them thought they would only be gone for a short time. They hoped to return to Cuba once the United States helped free it from Castro and communism.

More Cubans left after the Bay of Pigs Invasion failed. Castro then announced he was a Marxist-Leninist. This meant he followed communist ideas. This announcement made many people who were waiting to see what would happen decide to leave. This group was mostly middle class. It included merchants, managers, landlords, and skilled workers. These people worried when private schools and universities closed in 1961. This made their fears grow that the government would control their children's education.

Parents' Worries

By 1960, the Cuban government began changing how children were taught. School children learned military drills. They were taught how to use weapons. They also sang songs against the United States. By 1961, the Cuban government took control of all private schools.

Because of these changes, rumors began to spread. These rumors came from inside the United States and from anti-Castro news. Newspapers like the Miami Herald and Time Magazine reported things. They said Castro and his followers planned to take children from their parents. They also said the government would stop religious teaching. They would teach children only communist ideas. A radio station called Radio Swan, supported by the CIA, even claimed children would be sent to the Soviet Union. There was no real proof for these claims. But because of the way the Cuban government acted, people believed them.

These rumors, along with worries from the Spanish Civil War (when children were sent to other countries), made the patria potestad hoax impossible to stop. The Catholic church and the public heard these rumors. People who did not leave Cuba earlier began sending their children away for safety.

How the Exodus Was Organized

Father Bryan O. Walsh of the Catholic Welfare Bureau had helped young Hungarians come to the U.S. after the 1956 Soviet crackdown. With help from the U.S. government, he started the Cuban Children's Program in late 1960. Key people involved were Tracy Voorhees, the Eisenhower Administration, James Baker, and Father Walsh.

In October, a meeting focused on the many Cuban refugees in Miami. They noticed many children were alone in the city. Soon after, Tracy Voorhees, a U.S. government official, reported on the issue. He said that even though the number was not huge, it was getting a lot of attention. So, the government needed to show it was helping.

Before this, the Catholic church gave the most help. But by late 1960, President Eisenhower approved $1 million to help. Some money was for a Cuban emergency refugee center. Voorhees suggested the government get more involved. He wanted them to specifically help the Cuban refugee children. This would also help spread negative stories about Castro's Cuba.

At the same time, James Baker met with Walsh. Baker was the headmaster of an American school in Havana. Walsh was already helping child refugees settle in Miami. Baker told Walsh about his efforts to help parents send their children to Miami. Baker first wanted to create a boarding school in the U.S. for these children. But they both agreed that social welfare agencies would be better. The Catholic Welfare Bureau, Children's Services Bureau, and Jewish Family and Children's Services agreed to help. In November 1960, they asked for government money. They received it, following Voorhees' earlier suggestion.

Baker arranged the children's travel and visas. Walsh arranged places for them to stay in Miami. Secret groups of parents helped spread information. People like Penny Powers, Pancho and Bertha Finlay, Drs. Sergio and Serafina Giquel, Sara del Toro de Odio, and Albertina O'Farril helped tell parents about the program. To keep it secret, leaders in the U.S. did not communicate much with their contacts in Cuba.

How Operation Peter Pan Worked

Children Arrive in the U.S.

By January 1961, 6,500 Cuban children were in schools in Miami. By September 1962, this number grew to 19,000. Many people think of "Pedro Pans" as babies or very young children. But most of them were actually teenage boys.

There were no limits on how many children could come. The government also paid for foster care. This made the Cuban Children's Program different from others. It continued to grow and become more complex.

In January 1961, the U.S. embassy in Cuba closed. But Operation Peter Pan kept going. Instead of visas, children got special letters signed by Walsh. These letters allowed them to enter the country. Airlines were told to accept these letters as official papers. The U.S. government also paid for the flights.

Things continued to change. In September of that year, the State Department allowed Cuban child refugees to ask for visa waivers for their parents. For many families who could not afford it, or who had no relatives in the U.S., this became a common way for families to reunite.

How the Program Was Paid For

By late 1960, Castro had taken over several American companies in Havana. These included Esso Standard Oil Company and Freeport Sulfur Company. The leaders of these companies moved to Miami. They watched what Cuba's new government was doing. They thought Castro's rule would be short. So, they agreed to help fund Operation Peter Pan. Working with Baker, these business leaders agreed to get donations from many U.S. businesses. They would send the money to Cuba.

Castro was watching all major money transfers. So, the businessmen were very careful. Some donations went to the Catholic Welfare Bureau. Others were checks written to people living in Miami. These people then wrote checks to the W. Henry Smith Travel Agency in Havana. This agency helped pay for the children's flights to the United States. It was important to send money in American currency. Castro had ruled that plane tickets could not be bought with Cuban pesos.

Where Children Lived

More and more children arrived, so more shelters were needed. Several places were turned into homes for them. These included Camp Matecumbe and the Opa-locka Airport Marine barracks. Special homes were also created in many cities across the nation. These homes were approved by state officials. They were run by Cuban refugees. Cities included Albuquerque, New Mexico, Lincoln, Nebraska, Wilmington, Delaware, Fort Wayne, Indiana, Jacksonville, and Orlando, Florida.

Many children went into foster care. Some found good homes. Others faced emotional and physical neglect. Laws stopped children from being placed in reform schools or centers for young lawbreakers. Also, the children could not be adopted.

The End of the Operation

The Cuban Children's Program was kept secret until February 1962. That's when The Plain Dealer newspaper wrote about the many unaccompanied Cuban children. They had traveled across the country for three years without being noticed. On March 9 of the same year, the Miami Herald also published a story. Gene Miller wrote it. He was the one who first used the name "Operation Pedro Pan."

The U.S. part of Operation Peter Pan ended in October 1962. This happened after the Cuban Missile Crisis. All flights between the United States and Cuba stopped. Cuban immigrants then had to travel through Spain or other countries. They had to go through Spain or Mexico to reach the United States until 1965.

In December 1965, the United States started a program called Freedom Flights (los vuelos de la libertad). This program helped Cuban parents reunite with their children. The Catholic Welfare Bureau reported that almost 90% of the children still in their care were reunited with their parents once the Freedom Flights began.

Parts of the program continued until 1981. It is estimated that about 25,000 children were helped by this program.

What Happened After: The Legacy

Films About Operation Peter Pan

Near the end of this large movement of children, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy approved money for a propaganda film. This film was made to help migrant children understand why their parents sent them away. The film showed many things children could do in their new situation. This included learning, playing, and going to religious events. However, the film carefully avoided mentioning what was happening in Cuba. Cliff Solway, a Canadian director, made the film.

The film was called The Lost Apple. It was about thirty minutes long. It followed the lives of Roberto and two other young children. They lived in the Florida City Camp. This camp was one of the main places where children arrived. The United States Information Agency produced the film. Carlos Montalbán narrated it. The film explained to young Cuban children how and why they were in the United States. The narrator said that camps like Florida City Camp were only temporary. Children would find other chances through scholarships or live with foster parents.

Museums and Exhibits

The American Museum of The Cuban Diaspora (called The Cuban) had an exhibit about Operation Peter Pan. This was for its 60th anniversary in 2021. The museum is in Miami, Florida. It was started in 2004. The Cuban museum worked with Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc. (OPPG). They made OPPG's 2015 exhibit bigger. They added documents, objects, and pictures loaned by the organization's history committee.

The Pedro Pan Children

Many Pedro Pans found it hard to fit into American society. Their parents sent them to the United States. So, they often felt lost, both from their homeland and their new home. Some found the United States unwelcoming. It had racial segregation at the time.

Those who felt uncomfortable in American society often joined the growing Civil rights movement and anti-war movement. Some adopted the ideas of the youth counterculture. Others rejected their parents' beliefs. Many wanted to return to Cuba. At the same time, some found great success in their careers. They became famous people. For example, Maximo Alvarez founded Sunshine Gasoline Distribution Inc. He came to the United States as a Pedro Pan child in 1961 when he was 13.

Some Pedro Pan children joined the Abdala organization. This group of Cuban-American students protested the Cuban government. They also promoted Cuban-American pride.

Other Pedro Pan children developed leftist ideas. This happened after they joined social movements in the United States. In 1977, some Pedro Pan emigrants joined the Antonio Maceo Brigade. This group supported the Cuban government. They also helped Cuban exiles travel to Cuba. This brigade made the first trip of Cuban exiles back to Cuba.

A Look at Pedro Pan Children's Experiences

A study from Yale University looked at Pedro Pan adults. It wanted to see if they had lasting differences in their health. It also looked at how they felt about being separated from their families as children. These adults were compared to a group of Cuban immigrants. This control group had traveled with their families to the U.S. at the same time. 102 adults who were part of Operation Pedro Pan joined this study.

The study found no major differences between the Pedro Pan group and the control group. However, this result can be understood in different ways. Both groups were part of a larger group of exiles. So, they might have similar feelings about their families and that time period.

Different Stories About the Operation

The United States government might have had reasons other than just helping people. Allowing Cuba's middle class to leave weakened Cuba's economy. This was like a "brain drain." Stories of abandoned Pedro Pans made people in the Americas feel more strongly against Castro. It linked communism with families being separated.

In 1978, El Grupo Areito and Casa de las Américas published a book. It was called "Contra viento y marea". This book contained anonymous stories. They described feeling alone, both from the Cuban community they left and the American community they joined. These stories were very different from the happy tales of Operation Pedro Pan. They told of loneliness, bad living conditions, and emotional or physical harm.

People Who Were Part of Operation Peter Pan

Unaccompanied Cuban children, known as "Pedro Pans" or "Peter Pans," who were part of the operation include:

- Eduardo Aguirre, who became the United States Ambassador to Spain (2005–2009)

- Frank Angones, the first Cuban-born head of The Florida Bar

- Fred Beato, a Cuban-American musician and business owner

- Carlos Mayans, former mayor of Wichita, Kansas

- Willy Chirino, a Cuban-American musician and salsa singer

- Carlos Eire, author and professor of religious history at Yale University

- Felipe de Jesus Estevez, bishop of the Roman Catholic diocese of St. Augustine (2011–)

- Mario Garcia, a newspaper designer and media consultant

- Hugo Llorens, United States Ambassador to Honduras (2008–2011) and United States Ambassador to Afghanistan (2016–17)

- Ana Mendieta, an artist

- Guillermo "Bill" Vidal, former mayor of Denver (2011) and author of Boxing for Cuba

- Miguel Bezos, Jeff Bezos' (founder of Amazon) stepfather, who raised him from age 4

- U.S. Senator Mel Martinez, former Florida Senator and first Latino chairman of the Republican party

- Lissette Alvarez, a singer-songwriter

- Eduardo J. Padrón, former President of Miami Dade College (1995–2019)

- Demetrio Perez Jr., an educator, politician, radio commentator, business owner, and publisher of LIBRE, a bilingual weekly newspaper. He also founded the Lincoln-Marti educational group.

In Culture

Operation Peter Pan is talked about in:

- Waiting for Snow in Havana, where Carlos Eire writes about his experiences during Operation Peter Pan

- Learning to Die in Miami, another book by Carlos Eire about leaving Havana for the United States

- Operation Pedro Pan: The Untold Exodus of 14,048 Cuban Children, based on research and interviews by Yvonne M. Conde

- The Red Umbrella, a historical fiction novel for young adults by Christina Diaz Gonzalez. It is based on her mother's story of leaving Cuba as a teenager.

- Cuba on My Mind: Journeys to a Severed Nation, a book by Román de la Campa exploring Havana, Miami, and the "one-and-a-half-generation"

- Boxing For Cuba, a 2007 book by Bill Vidal, a civil servant and mayor of Denver

- "Operation Peter Pan", a song by Tori Amos. It was a B-side to her single "A Sorta Fairytale".

- The operation influenced the Manic Street Preachers song "Baby Elián". This song is on their album Know Your Enemy.

- On the 2017 Netflix show One Day at a Time, the grandmother, Lydia Riera (played by Rita Moreno), came to the US through Pedro Pan.

See also

In Spanish: Operación Peter Pan para niños

In Spanish: Operación Peter Pan para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |