Operation Tabarin facts for kids

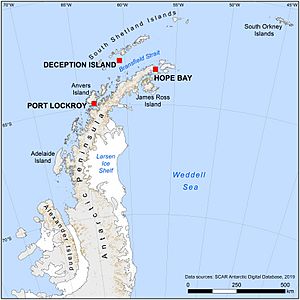

Operation Tabarin was a secret British journey to the Antarctic during World War Two, from 1943 to 1946. The main goal was to show that Britain owned certain lands in the Antarctic, called the Falkland Islands Dependencies. Other countries like Argentina and Chile also claimed these lands.

To do this, the British set up permanent bases. They also offered postal services and did scientific research. The weather observations they made helped Allied ships in the South Atlantic Ocean.

The expedition started planning in January 1943. It left the UK in November 1943, led by Lieutenant-Commander James Marr. In early 1944, two bases were built: Base B on Deception Island and Base A at Port Lockroy, Wiencke Island. Science and mapping work began. Fourteen men stayed through the winter of 1944.

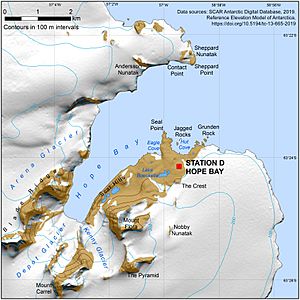

In the Antarctic summer of 1944/45, Captain Andrew Taylor became the new leader. This happened after Marr had to leave due to illness. A new hut was built on Coronation Island (Base C), but no one lived there. Base D at Hope Bay became the main center for the second year. More men, supplies, and 25 sledge dogs arrived to help with field work. Twenty-one men stayed through the winter of 1945.

In March 1946, a new group called the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS) took over. FIDS was created to continue the work of Operation Tabarin permanently. Later, in 1962, FIDS became the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). This happened after Britain signed the Antarctic Treaty.

Operation Tabarin set up the first year-round stations in the Antarctic. It started British scientific research in geology, biology, and mapping. The huskies brought by the expedition became the start of a British Antarctic husky population. These dogs were used for journeys for fifty years.

Contents

Why Was Operation Tabarin Needed?

When World War II started, Allied ships around the world were in danger. German Navy ships and U-boats attacked them. The war also made an old disagreement with Argentina about the Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute worse.

Important shipping routes around Cape Horn and the Cape of Good Hope were targets. This put the Falkland Islands and their nearby lands at risk. In January 1941, a German ship attacked Norwegian whaling ships. It captured a huge amount of whale oil.

Britain sent a ship to patrol the area. On March 5, 1941, this ship visited an abandoned whaling station on Deception Island. They destroyed coal and oil there. This was to stop them from falling into enemy hands.

When Japan joined the war in December 1941, the danger grew. Britain worried Japan might try to take the Falkland Islands. The islands had very few defenses.

In January 1942, Argentina sent a ship to Deception Island and other places. They raised Argentine flags and claimed these lands.

On January 28, 1943, British leaders met. They decided to send a ship to the Falkland Islands Dependencies. This ship would remove Argentine flags and put up British signs. Most importantly, they decided to set up permanent bases.

When the British ship reached Deception Island, it replaced the Argentine flag with the British one. A month later, Argentina's ship returned and put their flag back. Britain realized they needed to occupy the land to stop these back-and-forth actions.

The Expedition's Journey

How Was the Expedition Planned?

Planning for the expedition began in May 1943. The goal was to set up permanent bases on Deception Island and Signy Island. A new set of stamps was even made to help pay for it. Later, the second base location was changed to Hope Bay. This was because it was on the mainland.

An Expedition Committee was formed in June 1943. It included people from different government offices. They agreed that the expedition should do scientific research and mapping. Three scientists with Antarctic experience joined the committee. They helped plan the science work.

The expedition's secret code name was 'Tabarin'. It was named after a Paris nightclub because of all the night work and the busy planning. The expedition was meant to be top secret. But news of it leaked out by April 1944. This was partly because of the stamp work.

James Marr, a marine biologist and explorer, was chosen to lead the expedition. He had been on several Antarctic journeys before. Marr's first tasks were to find a ship and recruit volunteers.

It was hard to find a suitable ship during wartime. Marr found a Norwegian sealing ship called Veslekari. It was used for Arctic trips before. The ship was fixed up and renamed HMS Bransfield. Lieutenant Victor Marchesi became its captain.

Marr and the scientists chose the team members. Most were serving in the armed forces. They included a surveyor, a doctor, a meteorologist, a botanist, and geologists.

By late October, all the supplies were ready. The Bransfield was too small for everything. So, some cargo, like a prefabricated hut, was sent on other ships. The Bransfield itself was delayed due to leaks.

The Trip South

On November 12, 1943, Bransfield finally sailed. But it had problems and needed repairs. It proved unseaworthy in a storm. The expedition had to switch to a troop ship, SS Highland Monarch, on December 8. This ship was taking soldiers to the Falkland Islands.

They reached Port Stanley on January 26. There, they found HMS William Scoresby to replace Bransfield. Another ship, SS Fitzroy, was also assigned to carry cargo and most of the people.

First Year: 1943-1944

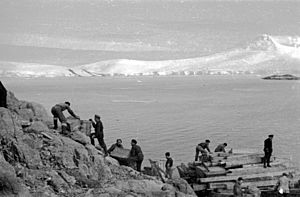

The two ships left Port Stanley on January 29. On February 3, 1944, they arrived at Port Foster, Deception Island. They found no signs of recent occupation, except for an Argentine flag painted on a fuel tank. They quickly erased it. They chose one of the old whalers' dormitories for Base B. Unloading began right away. By February 6, the ships left, leaving five men at Base B.

The expedition then sailed for Hope Bay. But thick ice made it too risky for the Fitzroy to enter. They had to give up on Hope Bay for then. They searched for another mainland site. With Fitzroy running low on coal, they decided to go to Port Lockroy, Wiencke Island. They arrived there on February 11.

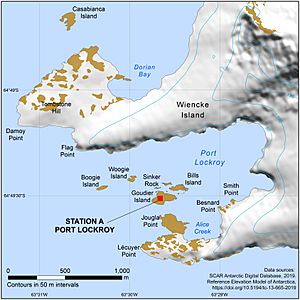

Port Lockroy was a well-known harbor. But its location limited some science work. It was also not on the mainland, which was less ideal for showing British ownership. Still, they chose a spot on Goudier Island for Base A. They started unloading cargo immediately. Any signs of Argentine claims were removed.

The main hut was named Bransfield House. On February 15, they set up the generator. This allowed them to talk to Stanley and Base B by radio. They added extensions to the hut later. Port Lockroy started postmarking mail on February 12. This showed how important the stamp duties were.

The William Scoresby and Fitzroy left the new base on February 17. They visited Base B, then Signy Island. They put a British flag on a hut there. Mail was processed using special stamps. Then they sailed to South Georgia before returning to the Falkland Islands.

The William Scoresby visited Base A two more times. On March 19, it brought John Blyth, who joined as a cook. On April 17, it delivered a lot of mail to be stamped. On April 22, Marr and others visited Cape Renard to put up a British flag and sign.

Both bases made weather observations. They sent these twice a day to Stanley. They also watched the sea ice in winter. At Deception Island, they sent up weather balloons. They also did geological surveys.

At Port Lockroy, science work began in early May. They collected rock samples. A botanist named Lamb studied lichens. He found new species, including the only known true marine lichen. This was a big discovery. During winter, the men practiced skiing. They also prepared for field trips. Taylor did local mapping. In September, four men surveyed Wiencke Island for 25 days. They pulled sledges in tough conditions. As spring came, Lamb studied the local beaches. Marr encouraged others to collect animal specimens. On November 18, Lamb led a trip to collect more plants and bird specimens.

Who Stayed for Winter 1944?

- Base A, Port Lockroy: James W.R. Marr (leader, zoologist), Lewis Ashton (carpenter), Eric H. Back (doctor, meteorologist), A. Thomas Berry (storeman), John Blyth (cook), Gwion Davies (handyman), James E.B.F. Farrington (radio operator), Ivan MacKenzie Lamb (botanist), Andrew Taylor (surveyor).

- Base B, Deception Island: William R. Flett (leader, geologist), Gordon A. Howkins (meteorologist), Norman F. Layther (radio operator), John Matheson (handyman), Charles Smith (cook).

Second Year: 1944-1945

On December 6, the William Scoresby returned to Base B. It brought plants and soil for Lamb to try a transplantation experiment. This experiment did not work. On February 3, 1945, the Fitzroy and another ship, the Eagle, arrived at Port Lockroy. They brought more men and supplies.

On February 7, Marr resigned due to poor health. Taylor took over as expedition leader. Taylor decided to focus on building Station D at Hope Bay. On February 13, Seal Point was chosen for Station D. Construction finished on March 20. On February 23, a hut was built on Coronation Island to strengthen British claims. The British expedition also visited the Argentine weather station on Laurie Island.

They collected some fossils at Hope Bay in February. More fossil gathering began on June 8. A sledging trip from Hope Bay started in August. On December 29, the sledging party returned. They had visited Vortex Island, Duse Bay, James Ross Island, and other islands.

This trip resulted in 250 kg (about 550 pounds) of lichen, fossil, and rock samples. They also took weather and glacier measurements. They even corrected some old maps made by Otto Nordenskjöld.

Who Stayed for Winter 1945?

- Base A, Port Lockroy: Gordon J. Lockley (leader, meteorologist, zoologist), John K. Biggs (handyman), Norman F. Layther (radio operator), Francis White (cook).

- Base B, Deception Island: Alan W. Reece (leader, meteorologist), Samuel Bonner (handyman), James E.B.F. Farrington (radio operator), Charles Smith (cook).

- Base D, Hope Bay: Andrew Taylor (commander, leader, surveyor), Lewis Ashton (carpenter), Eric H. Back (doctor, meteorologist), A. Thomas Berry (storeman, cook), John Blyth (cook), Gwion Davies (handyman), Thomas Donnachie (radio operator), William R. Flett (geologist), David P. James (surveyor), Ivan MacKenzie Lamb (botanist), Norman B. Marshall (zoologist), John Matheson (handyman), Victor I. Russell (surveyor).

Third Year: 1945-1946

On January 14, 1946, three ships began taking the expedition members back to the Falklands. On February 11, military members boarded HMS Ajax (22). The rest sailed home on Highland Monarch.

Images for kids

What Happened After Operation Tabarin?

After World War II ended, there was new interest in the Antarctic. The United States started Operation Highjump. Argentina and Chile signed an agreement to defend their "Antarctic Rights." Chile even sent its First Chilean Antarctic Expedition in 1947–1948. The Chilean President, Gabriel González Videla, became the first head of state to visit the continent.

Britain continued the bases built during Operation Tabarin. They transferred them to the new Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS). Some Operation Tabarin veterans stayed at their bases and kept working for FIDS. In 1953, people who took part in Operation Tabarin received the Polar Medal.

Port Lockroy made the first measurements of the ionosphere (a part of Earth's atmosphere). It also made the first recording of an atmospheric whistler (electronic waves). It was an important monitoring site during the International Geophysical Year of 1957. Port Lockroy is now a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 61) and a museum.

See Also

- British Antarctic Survey

- UK Antarctic Heritage Trust

- List of Antarctic expeditions

- Territorial claims in Antarctica

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |