Parkfield earthquake facts for kids

The Parkfield earthquake refers to several large earthquakes that have happened near the town of Parkfield, California, in the United States. This area is special because the famous San Andreas Fault runs right through it.

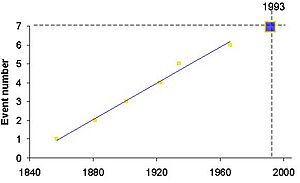

Scientists have noticed something very interesting about Parkfield. Six strong earthquakes, each about magnitude 6, happened on the fault here at very regular times. These quakes occurred between 1857 and 1966, usually every 12 to 32 years, with an average of 22 years between them. The most recent big earthquake in Parkfield was on September 28, 2004.

Earthquakes might happen so regularly here because of how the San Andreas fault works in this spot. Parkfield is located between two different parts of the fault. To the south, there's a "locked" section where the plates are stuck and build up a lot of stress. To the north, there's a "creeping" section where the two tectonic plates slide past each other slowly and continuously, causing fewer large quakes.

Contents

Studying Earthquakes in Parkfield

Scientists have been very interested in Parkfield because of its regular earthquakes. They hoped to learn what happens right before an earthquake. This could help them find signs that might allow them to predict future quakes.

Starting in 1985, geologists set up many special tools in and around Parkfield. These tools included seismometers (which measure ground shaking), creepmeters (which measure slow fault movement), and strainmeters (which measure changes in rock shape).

Scientists from the USGS and UC Berkeley believed there was a 90 to 95% chance that an earthquake would hit Parkfield between 1985 and 1993. This was part of a big project called the Parkfield Earthquake Experiment. However, a major earthquake (magnitude 5.5 or larger) did not happen during that time. Scientists continued trying to predict a quake until 2001, but the next big one didn't occur until 2004.

In June 2004, the USGS and the National Science Foundation started drilling a very deep hole. This hole was made to place instruments deep inside the fault. This project is called the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth (SAFOD). It helps scientists monitor the fault from deep underground.

Because large earthquakes (magnitude 5.5 or more) happened so regularly in Parkfield (in 1857, 1881, 1901, 1922, 1934, and 1966), scientists thought the same part of the fault was breaking each time. This led to the prediction in 1984 that a similar earthquake would happen in 1993.

The 2004 Parkfield Earthquake

The main earthquake in 2004 had a magnitude of 6.0. It happened because the fault moved about 18 inches (0.5 meters). Even with all the instruments, scientists found no signs that could have predicted this earthquake. Although it was expected, the chance of this quake happening in 2004 was only about ten percent. The strength of this earthquake was similar to the previous ones in the area.

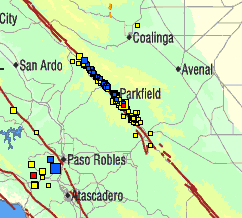

Many smaller earthquakes, called aftershocks, continued for more than a week after the main quake. These aftershocks moved towards the northwest. In early October 2004, a group of small earthquakes happened near Paso Robles. This area is near a fault that runs parallel to the San Andreas fault. These quakes might have happened because stress was transferred to these faults after the Parkfield earthquake released its stress. Past earthquakes have also occurred east of Parkfield, near Coalinga and Avenal.

New Discoveries About Faults

In December 2004, seismologists (scientists who study earthquakes) at the University of California, Berkeley found something new. They discovered very small tremors near Cholame, a small town south of Coalinga. This area is part of the "locked" fault section, which last caused a huge magnitude 8.0 earthquake in 1857, known as the Fort Tejon earthquake.

These tiny tremors were found using special seismometers placed deep underground. These deep sensors avoid noise from the surface. The signals from these tremors are more like the movement of magma near volcanoes than typical earthquakes. However, scientists believe these motions are not caused by magma or fluids.

Scientists hope this new discovery might help them understand how dangerous known "locked" faults are. They do not expect this information to become a precise tool for predicting earthquakes in the near future.

The 1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake

One of the largest earthquakes on the San Andreas fault in the last few hundred years was the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake. This earthquake caused the fault to break for about 360 kilometers (220 miles). The ground moved about 9 meters (30 feet) in some places. The break stretched from the Parkfield area all the way to San Bernardino in Southern California.

Scientists believe the starting point, or epicenter, of this earthquake was somewhere between Cholame and Parkfield. This location is at the very northern end of the "locked" part of the fault and at the southern end of the section that has regular earthquakes. It is also believed that a magnitude 6.0 foreshock (a smaller earthquake that happens before a larger one) occurred at Parkfield just before the main 1857 quake.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |