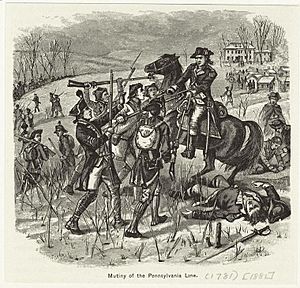

Pennsylvania Line Mutiny facts for kids

The Pennsylvania Line Mutiny was a protest by soldiers of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. These soldiers wanted better pay and improved living conditions. The mutiny started on January 1, 1781, and ended with an agreement on January 8, 1781. The final details were worked out by January 29, 1781. This event was the most important and successful protest by Continental Army soldiers during the war.

During the winter, some of the protesting soldiers gathered food, supplies, and horses. They planned to travel south to Philadelphia. Their goal was to speak directly to the Continental Congress, which was the government at the time. They wanted to present their demands in person. However, there is no sign that the soldiers intended to harm any members of Congress.

When the mutiny began at Jockey Hollow, which was the Wick family's home, soldiers tried to stop a young woman named Tempe Wick. She was riding home to her sick mother on her horse, Colonel. The soldiers demanded that she give them her horse, but Tempe refused. When they ordered her again to get off her horse, she cleverly rode back to the Wick House and hid her horse.

Even though the soldiers were unhappy with Congress and their officers, they did not join the British. British Army General Sir Henry Clinton offered them money if they would switch sides. The mutiny continued until the end of January. At that time, the government of Pennsylvania, called the Supreme Executive Council of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, started talking with the mutiny leaders. When they reached a good agreement, many soldiers returned to fight for the Continental Army. They took part in future battles. This successful protest inspired another similar one by the New Jersey Line soldiers, called the Pompton Mutiny. However, the New Jersey soldiers did not have the same good outcome. Their officers quickly brought order back to the army.

Contents

Why Did the Soldiers Protest?

During the winter of 1780–1781, the Continental Army was spread out into smaller groups. This made it easier to get supplies to them. The Pennsylvania Line had about 2,400 men. They were camped at Jockey Hollow, New Jersey, near Morristown. Conditions for the soldiers were very bad. Both General George Washington, who led the entire Continental Army, and General Anthony Wayne, who led the Pennsylvania Line, wrote letters about these terrible conditions. In earlier years, both Washington and Wayne had blamed corruption and a lack of care from state governments and the Continental Congress for these poor conditions.

Pennsylvania soldiers had special reasons to be upset. Pennsylvania was one of the states that paid its soldiers the least. Many soldiers in the Pennsylvania Line had served for three years. They had only received their first payment, a $20 bounty. Soldiers from other states were getting hundreds of dollars as enlistment payments. For example, new soldiers in New Jersey received a $1,000 bounty. Even new soldiers joining the Pennsylvania army received large payments. But the soldiers who were already serving did not get regular pay or money to re-enlist.

By January 1, 1781, the soldiers' unhappiness became very strong. Many "three-year men" believed their enlistment terms had ended. Their terms were "for three years or the duration of the war." They thought the new year meant their time was up. However, the officers of the Pennsylvania Line wanted to keep their soldiers. They believed the terms meant soldiers had to serve for the entire war if it lasted longer than three years. The Pennsylvania government later agreed that the soldiers' understanding of the terms was correct.

How the Mutiny Began

On January 1, 1781, the Pennsylvania Line soldiers had a very loud New Year's Day celebration. That evening, soldiers from several groups armed themselves. They got ready to leave the camp without permission. Officers tried to get the other soldiers to stop the uprising. But after the protesting soldiers fired a few warning shots, the rest of the groups joined them. Captain Adam Bitting, who led Company D of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment, was shot and killed by a protesting soldier. This soldier was trying to kill a different officer. Other than this, the uprising was fairly peaceful.

General Wayne tried to convince the soldiers to return to order peacefully. The soldiers promised they would not join the British. But they said they would not be satisfied until Pennsylvania fixed their problems. Wayne followed his troops and sent letters to Washington and the Pennsylvania government. The Pennsylvania Line set up a temporary base in the town of Princeton, New Jersey. They chose a group of sergeants to speak for them. This group was led by Sergeant William Bouzar, who had served in the British Army before.

Talking with the Soldiers

On January 5, the government of Pennsylvania learned about the mutiny. They immediately sent Joseph Reed, their president, to solve the problem. On the same day, George Washington sent a letter to the Continental Congress and several state governments. He asked again for supplies for the army. He explained the terrible conditions that led to the Pennsylvania Line mutiny.

Reed spent the night of January 6 in Trenton. There, he met with representatives from the Continental Congress. The government knew the protesting soldiers had public support. This included the support of the Pennsylvania militia. So, the government had to negotiate. On January 7, Reed arrived in Princeton to meet the sergeants. General Anthony Wayne first worried his men might not welcome Reed. But instead, Wayne and Reed had to stop the soldiers from honoring them with a cannon salute. They worried it might scare the local people.

Also on January 7, John Mason arrived in Princeton. He was sent by General Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in New York City. Mason was with James Ogden, a guide he found in New Jersey. The British agent brought a letter from Clinton. It offered the Pennsylvania soldiers their unpaid wages from British money if they stopped fighting for the American cause. Clinton had misunderstood why the Pennsylvania soldiers were protesting. The guards caught both the agent and his guide. The protesting soldiers did not immediately give Clinton's messengers to Wayne and Reed. But they showed good faith by telling them about the British offer and that they refused to accept it.

The talks went quickly. The soldiers focused their complaints on one main issue. They wanted men who had joined in 1776 and 1777 for $20 bounties to be released from service. Then, they wanted the chance to re-enlist for a new bounty if they wished. Reed heard stories that officers had forced soldiers to stay in the army or re-enlist with unfair terms. Some officers even used physical punishment to make them do so. Reed found these stories believable and agreed to the soldiers' terms. He even allowed that many soldiers whose enlistment papers were missing could simply swear an oath that they were "twenty dollar men" and be released.

What Happened Next?

Reed made plans in Trenton. The Pennsylvania soldiers marched there to start the release process on January 12. About 1,250 foot soldiers and 67 artillery soldiers were released. When the process ended on January 29, only 1,150 out of 2,400 men remained in the Pennsylvania Line. However, many soldiers who were released later joined the army again. The remaining groups of soldiers accepted their old officers.

After the mutiny, the Pennsylvania Line was reorganized. The 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th Pennsylvania Regiments were closed down. Their remaining soldiers were moved to older units. The 1st Pennsylvania Regiment was reorganized in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The 2nd also regrouped in Philadelphia. The 3rd was sent to Reading. The 4th went to Carlisle. The 5th went to York. And the 6th went to Lancaster. The regular soldiers, but not the sergeants and musicians, were all given time off until March 15. On that date, the groups met again in their towns. In May, General Wayne led the 2nd, 5th, and 6th Pennsylvania regiments south to join battles against the British in Virginia.

The British agent Mason was found to be a spy and faced severe punishment. Mason's civilian guide Ogden also faced severe punishment as a spy.

General George Washington, the leader of the Continental Army, was not happy with how the mutiny was handled. In a letter on February 2, 1781, he wrote that the Pennsylvania Line situation was settled by the state government. He felt this led to problems because other soldiers might try the same thing. He was talking about the Pompton Mutiny. In this event, Continental soldiers from the New Jersey Line were inspired by the Pennsylvania soldiers' success. They tried to achieve a similar outcome. Washington handled the Pompton mutiny very differently. He immediately sent Major General Robert Howe to Pompton. Howe surprised the protesting soldiers in their living areas. He made them surrender completely. Two of the soldiers who started the protest were punished right away.

In Books and TV

- One of Howard Fast's historical novels, The Proud and the Free (1950), tells this story from the point of view of the regular soldiers.

- Also, Ann Rinaldi's historical fiction novel A Ride Into Morning includes the mutiny.

- The mutiny is shown in “Nightmare,” the 4th episode of Season 4 of AMC’s “Turn” TV show.

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |