Percy Williams (sprinter) facts for kids

Percy Williams at the 1928 Olympics

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | May 19, 1908 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Died | November 29, 1982 (aged 74) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.70 m | |||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 56 kg | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Sprint running | |||||||||||||||||||

| Club | Vancouver Athletic Club | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Medal record

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Percy Alfred Williams OC (May 19, 1908 – November 29, 1982) was a super-fast Canadian runner. He won two gold medals at the 1928 Summer Olympics and even set a world record in the 100 metres sprint.

Contents

Early Life and Challenges

Percy was the only child of Frederick and Charlotte Williams. His dad was from England, and his mom was from St. John's, Newfoundland.

When Percy was 15, he got very sick with rheumatic fever. Doctors told him not to do hard sports. But his high school made everyone join sports. So, he started training in running in 1924. By 1927, he was a local running star!

Olympic Dreams Come True

At the 1928 Olympic tryouts, Percy won both the 100 and 200-meter races. He even tied the Olympic record for the 100 meters!

Percy and his coach, Bob Granger, worked hard to get to the Olympics. They worked as waiters and dishwashers on a train. Fans in Vancouver also helped raise money for Granger's trip to the 1928 Olympics.

Winning Gold in Amsterdam

In Amsterdam, Percy tied the Olympic record again in the 100 meters. He did this in both the second round and the semi-final. In the final race, Percy got a great start and won the gold medal!

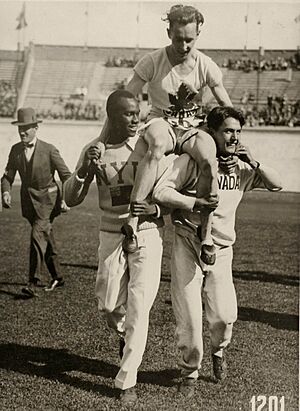

Two days later, he won the 200 meters too. He came from behind to pass another runner. Percy was the first non-American to win both sprint races at the Olympics. He ran eight races in just four days!

A Hero's Welcome Home

Percy's wins were huge news in Canada. He came home a national hero! About 25,000 people came to welcome him at the train station in Vancouver. The mayor and premier were there to greet him. They drove him through the city, which was filled with confetti. Reporters even broadcast the event live!

Setting a World Record

Percy showed his success was not just luck. In 1930, he set a world record at the Canadian Track and Field Championships in Toronto.

He then won the 100-yard dash at the first British Empire Games in Hamilton, Ontario. But during that race, he hurt his leg badly. He never fully recovered after that injury.

Later Olympic Games

At the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, Percy did not do as well. He was out of the 100-meter race in the semi-finals. His Canadian team also finished fourth in the 4x100 meter relay. After this, Percy stopped running and became an insurance agent.

Life After Running

In 1940, Percy joined the military reserves. He also worked as a civilian pilot during World War II, flying planes around Canada. Later, he taught others how to fly for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

In 1971, after his coach Bob Granger passed away, Percy was asked how much credit Granger deserved for his Olympic wins. Percy said, "Offhand, I'd say 100 percent."

Missing Medals and New Replicas

In the mid-1960s, Percy gave his two Olympic gold medals to the BC Sports Hall of Fame. He wanted people to see and remember them. Sadly, in 1980, the medals were stolen and never found. People thought they might have been melted down because gold prices were very high. Percy just shrugged off the loss.

However, in 2023, the International Olympic Committee made new replica medals for Percy's family. The family then gave these new medals to the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

Later Years and Recognition

In his later years, Percy became unhappy about his sports career. He even refused to go to the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal.

In 1979, he was given a high honor, becoming an Officer of the Order of Canada.

Percy never married and lived with his mother until she passed away in 1980. After that, he lived alone and suffered from bad arthritis pain. He passed away in 1982 and was buried in Burnaby, Canada.

Awards and Tributes

In 1950, a Canadian poll named Percy Williams Canada's greatest track athlete of the first half of the century. In 1972, he was called Canada's all-time greatest Olympic athlete.

A school in Toronto, Ontario, called Percy Williams Junior Public School, is named after him.

In 1996, Canada Post released a postage stamp of Percy Williams as part of its "Sporting Heroes" series.

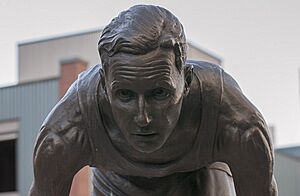

Outside the BC Sports Hall of Fame in BC Place stadium, there is a life-sized statue of Percy. It shows him in a sprinter's starting position.

Competition Record

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing |

|||||

| 1930 | British Empire Games | Hamilton, Canada | 1st | 100 y | 9.9 |

See also

In Spanish: Percy Williams para niños

In Spanish: Percy Williams para niños

- List of Canadian sports personalities

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |