Philip Murray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Philip Murray

|

|

|---|---|

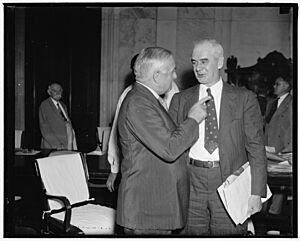

Murray in 1936

|

|

| Vice President of the United Mine Workers | |

| In office 1920–1942 |

|

| Succeeded by | Thomas Kennedy |

| 1st President of the United Steelworkers | |

| In office 1942–1952 |

|

| Succeeded by | David J. McDonald |

| 2nd President of the Congress of Industrial Organizations |

|

| In office 1940–1952 |

|

| Preceded by | John L. Lewis |

| Succeeded by | Walter Reuther |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 25, 1886 Blantyre, Scotland |

| Died | November 9, 1952 (aged 66) San Francisco, California |

| Occupation | Labor leader |

Philip Murray (May 25, 1886 – November 9, 1952) was a Scottish-born steelworker and an American labor leader. He played a huge role in helping workers get fair treatment and better pay. Murray was the first president of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) and later the first president of the United Steelworkers of America (USWA). He also served the longest as president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a major group of unions.

Contents

Early Life and Work

Philip Murray was born in Blantyre, Scotland, in 1886. His father was a Catholic coal miner and a union leader. Philip's mother passed away when he was only two years old. When Philip was 10, he started working in the coal mines to help his family. He had only a few years of school.

In 1902, Philip and his father moved to the United States. They settled near Pittsburgh and found jobs as coal miners. Philip was paid for each ton of coal he mined. A year later, they earned enough money to bring the rest of their family to America.

Joining the Union

In 1904, Philip Murray was working in a coal mine when he had a big disagreement. He felt a manager had cheated him by lowering the weight of the coal he mined. Murray confronted the man and was fired. Other miners went on strike to support him. The company then forced Murray's family out of their company-owned home. This made Murray realize how important unions were for protecting workers. He became a strong supporter of unions for the rest of his life.

In 1905, Murray was elected president of his local union in Horning, Pennsylvania. He wanted to be the best leader he could be. So, he took an 18-month correspondence course in mathematics and science. Even with little formal education, he finished the course in just six months.

Murray married Elizabeth Lavery in 1910. She was the daughter of a miner who died in an accident. They later adopted a son. In 1911, Murray became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Murray believed in working with company leaders rather than always fighting them. This caught the attention of John P. White, who became president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) in 1912. White appointed Murray to the UMWA executive board. Later, White supported Murray when he ran for president of UMWA District 5 in 1916.

Murray also became good friends with John L. Lewis, another powerful union leader. Murray supported Lewis in his rise to UMWA vice president in 1917 and UMWA president in 1920. In return, Lewis made Murray the UMWA vice president. Lewis focused on dealing with employers and politicians, while Murray worked closely with union members.

During World War I, Murray strongly supported America's involvement. He worked with government officials and companies to make sure workers helped with the war effort. President Woodrow Wilson even appointed him to important government committees. In the 1930s, Murray continued to serve on government groups. He helped write a law called the "Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935," which aimed to help coal miners.

Leading the Steelworkers

In 1936, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) removed several unions that wanted to organize workers by industry, not by craft. These unions then formed a new group called the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO). Philip Murray supported this new group and became a vice president.

When the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) was created in Pittsburgh on June 7, 1936, John L. Lewis chose Murray to lead it. Murray managed a large budget and many organizers.

Under Murray's leadership, SWOC had a big success. On March 2, 1937, they signed a contract with US Steel, a huge steel company. SWOC managed to get workers to join the union by working with existing company groups.

However, Murray and SWOC faced a tough challenge when they tried to organize smaller steel companies, known as "Little Steel." These companies fought hard against the union. They used many tactics to stop the organizing efforts.

In November 1938, Murray was elected second vice president of the CIO at its first official meeting. After the initial success with US Steel, organizing new members became harder. By 1939, SWOC was in debt.

President of the CIO

In 1940, John L. Lewis stepped down as CIO president, and Philip Murray was elected to take his place. The CIO was facing money problems because of the Great Depression and companies resisting unions. Lewis and President Franklin D. Roosevelt had different ideas about the war and government help for unions. Lewis even tried to get union members to vote against Roosevelt in the 1940 election. Despite this, Murray supported Roosevelt. Lewis himself nominated Murray for CIO president, and Murray was elected on November 22, 1940.

Forming the United Steelworkers

The "Little Steel" companies finally agreed to union contracts in the spring of 1941. Many workers went on strike, and court rulings helped the union. Workers at companies like Bethlehem Steel and Inland Steel voted overwhelmingly to join the union. Soon, Republic Steel also signed contracts.

Because of these victories, Murray decided to turn SWOC into a full-fledged union. On May 22, 1942, SWOC became the United Steelworkers of America (USWA). Murray was its first president. David J. McDonald, Murray's assistant, became the second-in-command. They ran the union in a very organized way. All union dues went to the main office, and the national union controlled contract talks and strikes. Murray felt this was necessary because steel companies had fought unions so hard.

Changes in the CIO

When Murray became CIO president, the organization was struggling financially. He quickly made changes to fix things. He collected unpaid dues, cut down on spending, and stopped supporting less successful organizing projects. He also reduced the CIO's reliance on money from the Mine Workers union. By November 1941, the CIO had extra money.

The relationship between Murray and John L. Lewis, his old friend, became strained. Lewis demanded that the CIO repay millions of dollars for past support. When Murray became president of the USWA, Lewis reacted strongly. On May 25, 1942, Lewis forced the UMWA board to remove Murray as vice president and take away his union membership.

World War II Efforts

During World War II, Murray strongly supported President Roosevelt and the war effort. He quickly promised that CIO unions would not go on strike during the war. He also supported ideas to increase production and solve design problems in factories.

To help reduce racial tensions in war factories, Murray created the CIO Committee to Abolish Racial Discrimination (CARD). This committee worked to educate people about discrimination. In 1943, Murray pushed for the Fair Employment Practice Committee to become a permanent government agency. Murray also served on other government groups to help with the war effort.

Post-War Challenges

In 1945, Murray attended the World Trade Union Conference in London with other union leaders.

In 1946, Murray led the Steelworkers on strike. Companies said they couldn't afford the wage increases the union wanted because of government price controls. President Harry Truman stepped in to help find a solution. The strike, which started in mid-January, ended within a month.

In 1947, Murray faced another challenge when Congress passed the Taft–Hartley Act despite President Truman's veto. This law limited some union activities. In 1943, Murray had created the CIO-PAC, the first-ever political action committee in the United States, to help unions in politics. However, the Republican Party still managed to pass the Taft–Hartley Act.

After the law passed, Murray and the CIO were accused of breaking a part of the act that stopped unions from spending money on federal political campaigns. The CIO had supported a candidate in Maryland and advertised it in their newspaper. The United States Supreme Court later ruled that publicizing endorsements was not against the law.

Murray also refused to sign an anti-communist statement required by the act, feeling it was insulting. However, Murray was not a radical. He strongly removed 11 left-leaning unions from the CIO in 1949 and 1950. In the 1948 election, Murray and the CIO supported President Truman and the Democratic Party.

Murray led the USWA through another successful strike in 1949. This time, the main issue was whether companies should pay for all of workers' health benefits and pensions. After a 31-day strike, Murray won a doubling of pension benefits, with the company still paying the full cost. The USWA agreed to pay half the cost of a new health and insurance benefit.

The 1952 Steel Strike

In 1952, Murray led the USWA in its most famous strike. During the Korean War, the government had put limits on wages to control inflation. In November 1951, the USWA asked US Steel for a large wage increase and better benefits. The company said they couldn't agree without government approval for higher steel prices.

President Truman sent the dispute to the federal Wage Stabilization Board (WSB). Murray agreed to delay a planned strike until the Board made its recommendation. In March, the WSB suggested a wage increase. Steel companies tried to stop any wage hike.

Congress threatened to overturn any agreement, but Truman refused to use the Taft–Hartley Act to stop the Steelworkers. Instead, on March 8, 1952, President Truman took control of the American steel industry.

The steel companies went to court to stop the government from taking over their mills. A federal judge first sided with the government, but later stopped the President from seizing the mills. The case went all the way to the United States Supreme Court. On June 2, 1952, the Supreme Court ruled that the president did not have the power to seize the steel mills.

The government returned the mills to their owners, and the Steelworkers went on strike for 51 days. The CIO did not have money to help the Steelworkers during the strike. John L. Lewis offered the union a $10 million loan, which made Murray feel embarrassed. Steel supplies started to run low, and Murray worried that the public might turn against the union for hurting the war effort. Truman even started preparing to draft steelworkers into the military, which further weakened Murray's resolve.

An agreement was reached on July 24, 1952. The Steelworkers won some benefits, but not as much as the WSB had suggested. Still, Murray and others saw the strike as a big victory. They had avoided the harsh rules of the Taft–Hartley Act, and Truman had gone to great lengths to support the union.

Death

Murray did not get to enjoy his victory for long. In the November 1952 presidential election, Dwight D. Eisenhower won, and Republicans gained control of Congress. This was another setback for the CIO-PAC.

Philip Murray died in San Francisco on November 9, 1952, from a heart attack. Walter Reuther became the next president of the CIO, and David J. McDonald became the new president of the Steelworkers.

He is buried in Saint Anne's Cemetery, in Castle Shannon, Pennsylvania.

Other Roles and Writings

Philip Murray was very involved in his community. From 1918 until his death, he was a member of the Pittsburgh Board of Education. He was also a long-time member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served on its executive committee. He was also on the board of directors for the American Red Cross.

Murray wrote one book during his life called Organized Labor and Production, which was published in 1940.

Images for kids

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |