Pietru Caxaro facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Caxaro

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1400 |

| Died | August 1485 |

| Occupation | Philosophy, Poetry |

Pietru "Peter" Caxaro (around 1400–1485) was a Maltese thinker and poet. He is known as Malta's very first philosopher. We still have parts of his writings today. His ideas show he was a strong supporter of the humanist movement in the Middle Ages. His work truly reflects the new ideas and culture of his time.

Caxaro's education and his humanist way of thinking, along with his philosophy, perfectly show the unique spirit of the Maltese people. They lived in the Mediterranean region, and their best times were still to come. But their way of thinking and expressing themselves was already well-formed. Finding out about Caxaro and his ideas helps us understand this ancient civilization even better.

No pictures of Caxaro have ever been found.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Peter Caxaro was born into a noble family in Mdina, Malta. We don't know his exact birth date, but it was probably around the early 1400s. His father was named Leo, and his mother was Zuna. Some people think his family might have been of Jewish background and were later asked to become Christians.

Peter had a brother named Nicholas. In 1473, Nicholas was killed after an argument with people from Siġġiewi, Malta. This happened because he was secretly seeing a girl.

Caxaro started his studies in Malta. Later, he traveled to Palermo, Sicily, to continue his education. Palermo was a busy city back then, full of the new ideas of the Renaissance (a time of great change and new art).

Career and Public Service

In Palermo, Caxaro finished his studies and became a notary in 1438. A notary is someone who can legally witness and prepare documents. Just a few months after graduating, he became a judge in Gozo for two years (1440-1441). He also served as a judge in Malta in 1441 and again in 1475.

Caxaro was a judge in civil courts (for disagreements between people) in 1460-1461, 1470–1471, and 1481–1482. He also served as a judge in church courts in 1473 and 1480-1481.

Besides being a judge, Caxaro was a jurat (a kind of council member) for the Town Council of Mdina. He held this role many times between 1452 and 1483. He also worked as a notary or secretary for the same council in 1460 and 1468. Caxaro owned a lot of land in northern Malta and had six slaves working for him.

Friends and Challenges

Caxaro was very good friends with the Dominican friars. They had a monastery in Rabat, Malta, which was close to Mdina, where Caxaro lived and worked. The Dominicans arrived in Malta around 1450. They quickly became friends with educated people, including scholars.

Caxaro was close to some of these friars. This was for both intellectual reasons and personal friendship. He even named the Dominicans as the main inheritors in his will, showing how much he trusted them.

Around 1463, Caxaro wanted to marry a widow named Franca de Biglera. However, Franca's brother, who was a church official, objected. He said Caxaro's father had been a godfather to Franca, which created a "spiritual family connection" that made marriage difficult. Even though Caxaro tried his best and got the bishop's approval, Franca changed her mind. Caxaro never married and remained single his whole life.

Standing Up for What's Right

In the Town Council of Mdina, Caxaro cared deeply about three things: keeping his hometown of Mdina in good shape, educating ordinary people, and making sure public officials were honest.

In 1480, Caxaro bravely spoke out against the bishop of Malta, who was suspected of being corrupt. Caxaro strongly demanded that the problem be fixed right away. In return, the bishop punished him by excommunicating him in June 1480. This was a very serious punishment back then. But Caxaro did not give up. The bishop then tried to stop him from taking part in church life. Still, Caxaro remained determined.

The issue continued until the next year. Finally, the bishop had to agree to Caxaro's and the Town Council's demands. The punishments were removed. Caxaro was highly praised for his strong will and determination.

Death and Burial

On August 12, 1485, Caxaro wrote his will. He died a few days later, though the exact date is not known. All his belongings went to the Dominican friars.

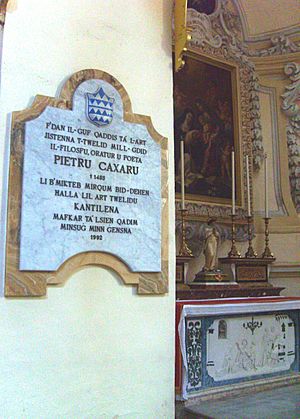

We don't know where he was first buried. But later, as he wished in his will, his body was moved. He was laid to rest in one of the new chapels of the church of St. Dominic in Rabat, Malta. Caxaro had paid for this chapel himself, and it was dedicated to Our Lady of Divine Help. A memorial was placed over Caxaro's tomb in this chapel on September 30, 1992.

Caxaro's Writings

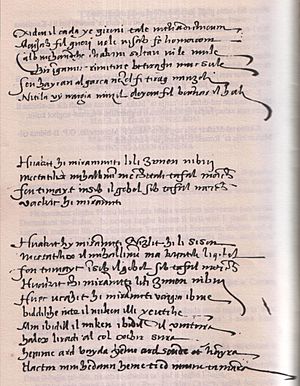

The Cantilena Discovered

Peter Caxaro was mostly unknown until 1968. That year, his poem called Cantilena was published by two Dominicans, Mikiel Fsadni and Godfrey Wettinger. Fsadni found the Cantilena on September 22, 1966. It was written on the back of a page in an old book of notary records from the 1500s. The poem was copied by a notary named Reverend Brandan Caxaro.

This discovery was very exciting for scholars. It gave Maltese literature a huge boost. It took Fsadni and Wettinger about two years to prepare the Cantilena for the public. They carefully checked the document and were sure it was real.

Before 1968, only a few scholars had mentioned Peter Caxaro. The first was Paul Galea in 1949. Later, Michael Fsadni also wrote about him in 1965. Both based their information on older writings from the 1600s.

Who Was the Author?

When Reverend Brandan copied the Cantilena, he described its author as a "philosopher, poet, and orator" (a skilled public speaker). Experts believe Caxaro originally wrote the poem in the Maltese tongue. Reverend Brandan then copied it as accurately as he could remember. The poem itself shows that Caxaro was indeed a skilled philosopher, poet, and speaker. He was clearly a very educated man.

Recently, some people have suggested that Peter Caxaro might not have written the whole poem. They thought it might be an old Arabic or Spanish poem copied by Reverend Brandan. However, these ideas were not based on scientific evidence. Most experts agree that Caxaro was a talented writer. He was good at using sounds and classical speaking techniques. He could express deep thoughts in a clever and inviting way. The Cantilena is a beautiful piece of writing, showing great skill and unique style.

It's interesting that Giovanni Francesco Abela, in his 1647 book about Malta, didn't include Caxaro in his list of famous Maltese people. This might mean that Caxaro's talents were not widely known during Abela's time.

We know about Caxaro from a few old records. These include archives in Palermo, Sicily, the National Library of Malta, and the Dominican archives in Rabat. The first known date for Caxaro is April 1, 1438. This is when he took an exam in Palermo to become a public notary for Malta and Gozo. At that time, Malta was part of the Kingdom of Aragon. Palermo was a city full of new humanist ideas.

Caxaro held many important jobs in Malta and Gozo between 1440 and 1483. He was a judge in civil and church courts. He was also a council member and sometimes secretary for the Mdina city council.

We also have a large part of his will, written on August 12, 1485, shortly before he died. His will does not mention a wife or children. Caxaro wanted to be buried in the new Dominican church in Rabat, in a chapel he paid for. This chapel was dedicated to the "Most Glorious Virgin of Help."

We know for sure that Peter Caxaro was born in Malta to Maltese parents and lived in Mdina. His exact birth date is still a mystery. He owned a good amount of property and had at least six slaves.

Two other personal stories about Caxaro are known. One is about his attempt to marry Franca di Biglera in 1463 or 1478. Court records from this time show that Caxaro's father often visited Catalonia (especially Barcelona and Valencia). This might have influenced Peter's own education. The second story is about his brother Cola's death in 1473.

In 2009, Frans Sammut suggested that Caxaro came from a Jewish family that had become Christian. He thought Caxaro's Cantilena might be a zajal, a type of song popular among Jews in Spain and Sicily.

Remaining Fragments

Very little of Caxaro's scholarly work still exists. We only have small parts of his writings. The Cantilena is the most complete, but even it comes to us through an old copy that might have some errors.

It's clear that Brandan's copy of the Cantilena has some mistakes. For example, some lines don't rhyme. Scholars like Joseph Brincat noticed these problems in 1986. He believed that some parts were copied incorrectly. Other scholars agree with this idea.

Besides the Cantilena, we have other fragments of Caxaro's work. These include some legal decisions he made as a judge in church courts. We also have notes from the Mdina town council meetings where Caxaro was present. These documents show his balanced and serious nature. However, they don't reveal his original philosophical thoughts, only legal and official language.

The municipal records also give us information about Caxaro's involvement in matters important to Mdina and the Maltese Islands. Caxaro's name is mentioned in at least 267 council meetings between 1447 and 1485. In some, he had a small role, but in others, he played a more important part. Some of these records are even written in Caxaro's own handwriting.

The Philosopher

Reverend Brandan called Caxaro a "philosopher." In the rest of the Cantilena's introduction, Brandan focuses more on Caxaro's poetic skills, leaving his philosophical and speaking talents in the background. Some people thought "philosopher" just meant a wise or learned person. But since Reverend Brandan was a careful notary, he likely meant "philosopher" in a strict sense. We hope to find more evidence to support this.

It's not new in history to find a philosopher's ideas from only a small piece of their writing. Many great philosophers, like Aristotle, are known from fragments. The fact that Caxaro's philosophy is in a poem is also not unusual. Some famous philosophers, like Parmenides, also wrote in poetic form.

Caxaro's philosophy is more like Plato's style. Plato, unlike scientists, was an artist before being a philosopher. This means Caxaro's work focuses more on storytelling than on strict, systematic arguments. This style was common among humanists in the early Renaissance. It emphasizes human feelings and knowledge gained through desire. It also values human thinking abilities as necessary to find true knowledge, which is deeper than what our senses tell us.

A Humanist Spirit

Caxaro's connections to Barcelona, Valencia, and Palermo are important. They show his humanist background.

Humanism in Catalonia

Catalonia, along with Aragon, embraced humanism early on. Catalan scholars first encountered this movement at the Pope's court in Avignon and at important church councils. They also met humanists at the court of King Alphonse V of Aragon in Naples.

The humanist movement in Catalonia started with Juan Fernandez in the 1300s. He traveled to the East, brought back many Greek writings, and became a translator. This led to a new culture focused on human interests. Other important scholars followed him, studying works by Aristotle, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. They helped spread humanism in Barcelona and Valencia.

It's likely that Caxaro's father, who traveled often between Catalonia, Sicily, and Malta for trade, came into contact with these humanist ideas. Humanism wasn't just for scholars; it became a way of thinking for many people in these Mediterranean cities. Caxaro and his family, like many others, were part of this exchange of goods and ideas.

Humanism in Palermo

King Alphonse the Magnanimous of Aragon made his court in Naples a brilliant center of the Renaissance. Naples and its sister city, Palermo, were visited by top humanists from all over Italy and Spain.

From the early 1400s, Palermo grew a lot in economy, population, and city design. It also had a big cultural change. Even with challenges like Turkish attacks and diseases, many people were interested in humanist studies. Before Caxaro's visit, scholars like Giovanni Aurispa made a name for themselves in Palermo.

Humanism came to Sicily from Northern Italy, where many people from Palermo went to study. Before 1445, Palermo attracted the most law students. These places were where classical texts were shared, mostly as handwritten copies. In those days, many educated people and law students saw legal knowledge as a way to gain social standing. This professional focus, especially in law, became a key part of Palermo's new atmosphere.

When young Caxaro visited Palermo in 1438, he must have been amazed by the city's new buildings and renovations. The whole city was focused on improving life quality. The humanist spirit brought new ideas in art, philosophy, science, and religion. It sharpened the idea of beauty and improved the connection to nature.

Caxaro's time in Palermo must have reminded him of King Alphonse's visit to Malta five years earlier. The King, full of the spirit of the time, entered Mdina, Caxaro's hometown, with great joy and applause from his loyal people.

The Spirit of Mediaeval Humanism

To understand Caxaro's philosophy, we need to grasp the spirit of humanism in his time. Mediaeval humanists, unlike earlier thinkers, focused on finding and copying the beauty of ancient writings. This wasn't against Christianity, but it strongly emphasized nature. The idea of copying "pagan" ancient customs came later.

Humanism began during a difficult time for the Catholic Church, with the Eastern Schism weakening the Pope's power. There was also a lack of knowledge among clergy, relaxed rules, corruption among the rich, and a decline in traditional scholarly methods.

Early humanists had a powerful impact. The works of Brunetto Latini, Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, and Giovanni Boccaccio were essential reading for humanists. They greatly admired ancient times, seeing them as glorious and dreaming of an ideal society like that.

Ironically, the sad and pessimistic writer Petrarch had the biggest influence. He believed, like Socrates, that true wisdom comes from knowing oneself, and humility leads to life's secrets. His support for Plato and his strong criticism of traditional scholarship deeply impressed those who followed him. Petrarch gave the humanist movement its rallying cries: Rinascere! Rifiorire! Rivivere! Ritrovare! (Rebirth! Flourish! Revive! Rediscover!) – emphasizing the idea of "re-" or "again."

This humanist rebirth was felt across Western Europe. It was a cultural peak of the Middle Ages, bringing back Latin, Greek, and Christian classical literature with its techniques and styles. It led to new sciences like philology (study of language in historical sources), archaeology, and history. It also led to the printing press, new libraries, universities, and literary groups. This was a true "renaissance" with its own philosophy that valued human dignity. It made humans, as Protagoras said, the "measure of all things," focusing on human nature and its interests.

The Cantilena Poem

The Cantilena has been studied a lot in the last 25 years. People have discussed the strange inconsistencies in the existing copy. Its literary value and importance in Maltese literature have also been praised.

More interesting ideas have come from looking at it as a piece of literary criticism. However, more work is needed, especially by experts in mediaeval Arabic, Spanish, and Sicilian languages and poetry. The Cantilena's unique nature has also helped us understand how much the Maltese language has changed over four centuries.

What interests us here is the Cantilena's philosophical meaning. Here is the poem:

-

- Xideu il cada ye gireni tale nichadithicum

- Mensab fil gueri uele nisab fo homorcom

- Calb mehandihe chakim soltan ui le mule

- Bir imgamic rimitine betiragin mecsule

- fen hayran al garca nenzel fi tirag minzeli

- Nitila vy nargia ninzil deyem fil-bachar il hali

-

-

- [Omission]

-

-

- Huakit hy mirammiti Nizlit hi li sisen

- Mectatilix il mihallimin ma kitatili li gebel

- fen tumayt insib il gebel sib tafal morchi

- Huakit thi mirammiti lili zimen nibni

- Huec ucakit hi mirammiti vargia ibnie

- biddilihe inte il miken illi yeutihe

- Min ibidill il miken ibidil il vintura

- halex liradi ‘al col xebir sura

- hemme ard bayda v hemme ard seude et hamyra

- Hactar min hedaun heme tred minne tamarra

Here's what it means in English:

-

- The story of misfortune, O my neighbors, come I’ll tell you

- Such as has not been found in the past, nor in your lifetime.

- A heart ungoverned, kingless, and lordless

- Has thrown me into a deep well with steps that stop short;

- Where, desiring to drown, I descend by the steps of my downfall;

- Rising and falling always in the stormy sea.

-

- My house has fallen! It has pushed the foundations.

- The workmen did not trespass, the rock gave way.

- Where I had hoped to find rock, I found loose clay.

- The house I had long been building has collapsed.

- And that’s how my house fell! And build it up again!

- Change the place that harms it.

- He who changes the place changes his fortune;

- For each land makes a difference with every span;

- There is white land and black and red land;

- More than this, there is that from which you’d better leave.

Caxaro's Philosophical Ideas

Given what we know about Caxaro's background, here are some of his philosophical ideas. These are just starting points to help us understand his views.

Using the Local Language

First, it's very important that Caxaro used the Maltese common language. This was a big step forward, showing his humanist education. Choosing to express himself skillfully in the language of the people, instead of Latin or Sicilian (used by the educated), shows Caxaro's true quality. It wasn't just a choice of language. It was a commitment to a way of thinking unique to Malta.

It also shows the value he placed on local culture and heritage. He believed it could stand on its own, equal to other nearby countries. Using the Maltese language wasn't a call for independence. It was an affirmation of a people's native identity.

Focus on Humankind

Another important point is the everyday, non-religious theme of Caxaro's poem. This is another sign of his humanist character. The Cantilena is not against religion, but it's not about sacred or biblical topics. It's not disrespectful, but it looks at life, people, and their surroundings from a human point of view.

The poem talks about the special qualities of human nature. These are the abilities that show how amazing humans are. They also show our power to overcome the difficult limits of our nature. Caxaro's poem shows a strong belief in the spiritual, or non-physical, possibilities of humans. The Cantilena can be seen as a declaration of faith in humankind.

This belief reminds us of the classical humanism of the Sophists and Socrates. This school of thought greatly inspired early Renaissance philosophy. It moved beyond just looking at nature. It put humans at the center of serious thought. The classical idea of finding natural solutions to old problems, instead of only religious ones, is important here.

Reality and Experience

Caxaro's thoughts are very practical and clear. He avoids dry, academic language and complicated ideas. He prefers a practical, real-life view of life and reality. This might be a typical Maltese or Mediterranean trait, where common sense is very important in daily life.

Caxaro preferred action over deep thinking. This shows his leaning towards the Platonic school of thought, and away from the more structured ideas of Aristotle and traditional scholars. This is another strong part of his humanist character.

Storytelling vs. Logic

In Caxaro's work, storytelling doesn't mean being shallow. It also doesn't mean he couldn't express himself in more formal terms. Storytelling can be a scientific way of expressing ideas. It's a traditional technique with a rich history. It avoids being overly complicated, choosing a more flowing, free, and inclusive way to communicate.

Caxaro's poem, like Plato's writings, uses a hidden language and meaning. This makes us want to actively guess the hidden message beneath the simple surface. Unlike a very technical style, which is often rigid, Caxaro's philosophy is presented as a story that has its own reality.

While Caxaro clearly states some of his ideas, especially about the unpleasantness of illusion, he prefers to express himself in a "deceptive" way. The true meaning of his philosophy is cleverly hidden behind a screen. A simple look won't reveal it.

Allegory and Symbolism

Caxaro's story isn't a simple moral tale. It's not useful to look for an exact match between every image he uses and real-life events. This is why the idea that the poem is about his "marriage proposal" shouldn't be taken too seriously. That idea takes away from the poem's rich qualities.

There are connections in the Cantilena between the different symbols Caxaro uses. He doesn't just show an image to copy its outside form. He creates a harmony of meanings among his symbols. He connects them to his view of the world as a single, connected whole.

The use of allegory in Caxaro's Cantilena means that a subject is presented through a story that suggests similar characteristics. Caxaro is probably not talking about one single event, but about a general life situation. Using an allegory encourages deeper thought. It opens us up to the mystery and puzzle of life.

Truth vs. Appearance

This is a very important theme in the Cantilena. It might be the most important idea in the whole poem. The line "Where I hoped to find rock I found soft clay" (v. 9) gives us a clue. This might be the key to understanding the poem's mystery. Here, we see a false truth next to the real truth.

In simple terms, this is a problem about reality itself. It's about humans facing a reality that is hidden and covered by what we immediately see and feel. Caxaro compares what appears to be real (what our senses tell us) with what is truly real (what our minds understand). Caxaro emphasizes experience. Our senses are the tools we use to reach what is real.

This theme echoes Plato's most basic idea. Plato contrasts what appears to be real with the truth, which he connects to life. Appearance stays at the level of things that aren't truly important, except as a way to think. A shallow life comes from always being superficial. But the ability to get to the heart of things, to the truth of reality, to life itself, would make this appearance unimportant.

Metaphysics (Understanding Reality)

Caxaro's philosophy about reality, knowledge, and the human mind starts with the real experience of defeat and helplessness (see v. 7). This isn't just a moment of sadness, but a state of being. It's the feeling of humans helplessly giving in to a reality that is too big for them.

From thinking about this state of being, Caxaro finds the humanist drive to break free from this humiliating condition. He does this by rediscovering the inner spiritual power within humans. "And build it up again!" (v. 11) reminds us of Petrarch's call for rebirth. It's about blooming again from the dust. This is a key moment in renewing faith and confidence in oneself to overcome helplessness.

Action now becomes important (see v. 12). The distorted view of reality, the false appearance that ruins human life, must be replaced by a fresh, new understanding. This is a spiritual decision, based on knowledge, to choose a higher quality of life. It means choosing the truth, even if it's difficult, instead of a false truth.

This is also a choice for science, religion, and individual personality. All of this is against false science, false religion, and false personality. So, humans are indeed vulnerable to the puzzle of existence (see vv. 13-14). It is their ability to truly understand and use their judgment correctly (see vv. 15-16) that gives them the right direction.

Communication and Symbols

The way Caxaro starts the Cantilena is part of a general theory of language. It's based on two things: Caxaro's own examined life (an idea from Socrates and Plato to Petrarch), and sharing that experience.

This is different from teaching an abstract theory. It suggests that the person communicating is more important than the message itself. A story about a personal experience doesn't rely on the listener's understanding. It relies on their feelings, which are somewhat universal. In other words, it asks for shared emotions.

Caxaro's story, where he takes a clear philosophical stand, is not meant to be a moral lesson or a strict rule. The story is an announcement of discovering an important non-physical world, beyond mere appearances.

In this context, we can easily understand the nature of the language Caxaro uses. It's a way of expressing himself that is open and flexible, matching his general philosophy. It's also based on the idea of connections between things.

Caxaro doesn't seem to use images randomly. He creates a harmony of meanings among the symbols he uses. He takes advantage of how they relate to each other. He also shows them in connection with his world, seeing that world as a single, unbreakable whole.

Caxaro's symbols, like those of ancient Maltese structures and later Greek philosophers, are not simple or artificial. They don't mean the author identifies with the images themselves. Caxaro's unique way of expressing himself suggests a deeper spiritual connection between all matter. This is a philosophy very common among mediaeval philosophers, especially those who followed the Platonic school.

The qualities of the symbols he uses are important. These include the heart (v. 3), the well (v. 4), the steps (vv. 4, 5), the water (v. 6), the house (vv. 7, 10, 11), the foundations (v. 7), the rock (vv. 8, 9), the land (vv. 12, 13, 14, 15), and the colors (white, black, red, v. 15). All these symbols relate to human qualities and are part of a connected reality.

Each symbol Caxaro uses is given a description, which changes its absolute meaning. At the same time, he recognizes their temporary existence in relation to humans. For example, the heart is described as "ungoverned, kingless, and lordless" (v. 3). The well is "deep" (v. 4). The steps "stop short" and lead to "downfall" (v. 4). The water is "stormy" or "deep" (v. 6). The house is one he "had long been building" (v. 10).

Other symbols are described indirectly. The foundations are "soft clay" (v. 9). The rock "gave way" (v. 8). The land is connected to "fortune" and "difference" (vv. 13, 14). The colors are linked to the "land" itself (v. 15). These descriptions are as important as the connections between the symbols themselves.

See also

- Philosophy in Malta

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |