Pingo facts for kids

Pingos are special hills with an ice core inside them. They are usually shaped like a cone and can be from 3 to 70 meters (about 10 to 230 feet) tall. They can also be quite wide, from 30 to 1,000 meters (about 100 to 3,300 feet) across. Pingos only grow and last in places where the ground is always frozen, called permafrost. You can find them in cold regions like the Arctic and subarctic areas.

A pingo is a type of periglacial landform. This means it's a landform that isn't made by glaciers but is linked to very cold climates. Scientists believe there are over 11,000 pingos on Earth. The area around Tuktoyaktuk in Canada has the most pingos in the world, with about 1,350 of them!

Contents

Discovering Pingos

The first time a pingo was described was in 1825 by John Franklin. He climbed a small pingo on Ellice Island in the Mackenzie Delta. But the word pingo itself wasn't used until 1938. It was borrowed from the Inuvialuit people by a botanist named Alf Erling Porsild. He used it in his paper about Earth mounds in the western Arctic. The word "pingo" means "conical hill" in Inuvialuktun, the language of the Inuvialuit. Today, it's a common scientific term. There's even a pingo named Porsild Pingo in Tuktoyaktuk to honor him.

How Pingos Form

Pingos can only form where there is permafrost. If you find a collapsed pingo, it's a sign that permafrost used to be there. When a pingo collapses because its ice core melts, it's sometimes called an "ognip" (pingo spelled backward).

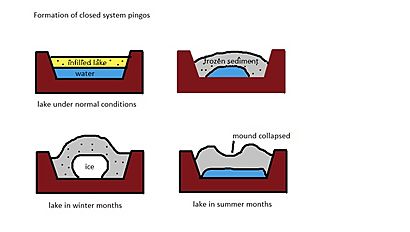

Closed-System Pingos

These pingos are also called hydrostatic pingos. They form when water gets trapped under the ground and builds up a lot of pressure. This happens in areas with continuous permafrost, where the ground is completely frozen and doesn't let water pass through.

You often find these pingos in flat, wet areas like shallow lakes or river deltas. Here's how they form:

- Imagine a shallow lake that slowly fills up with dirt and plants. This dirt acts like a blanket, keeping the water underneath from freezing right away.

- In winter, the ground around the lake freezes. This freezing ground pushes inwards and upwards.

- The water trapped under the lake bed gets squeezed. This pressure forces the water upwards, creating a mound of earth.

- As the water keeps getting pushed up, it freezes into a large ice core, making the pingo grow taller.

- In summer, the top of the pingo might melt a bit, causing the mound to sink slightly.

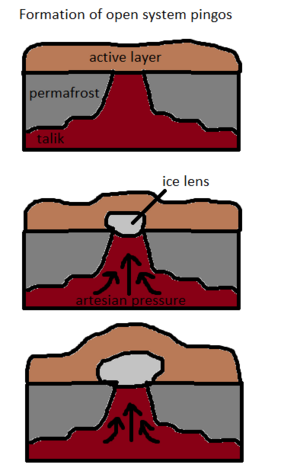

Open-System Pingos

Open-system pingos, also called hydraulic pingos, form differently. They get their water from an outside source, like underground rivers or aquifers (layers of rock that hold water). This water is under pressure, like water in a hose.

Here's how they form:

- Water from an underground source is pushed upwards.

- When this water reaches the cold permafrost, it freezes and starts to form an ice core.

- Unlike closed-system pingos, open-system pingos have a constant supply of water, so they can grow very large.

- They often appear at the bottom of slopes.

- These pingos usually form in areas where the permafrost is thinner or has gaps. This allows the water to flow up from below.

- If the water pressure is strong enough, it can even lift the pingo, creating a pocket of water underneath.

- Open-system pingos are often oval or oblong in shape.

Pingos usually grow very slowly, only a few centimeters each year. The largest ones can take hundreds of years to form! A pingo's base usually reaches its full width when it's young. After that, pingos tend to grow taller rather than wider. Smaller pingos often have rounded tops, but larger ones might have collapsed tops or craters because the ice inside has melted.

Where to Find Pingos

Pingos are found in many cold parts of the world.

Greenland

Greenland has many pingos. In western Greenland, there are about 29 pingos, and in eastern Greenland, there are about 71. Most of them are in places like Disko Bay and Nuussuaq Peninsula. The permafrost in Disko Bay is about 150 meters (about 490 feet) deep, which is perfect for closed-system pingos to form. The largest pingo on Disko Island is 100 meters (about 330 feet) wide and 15 meters (about 49 feet) high.

In eastern Greenland, pingos are found in Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden. The largest one there is 100 meters (about 330 feet) wide and 8 meters (about 26 feet) high. It's still growing taller!

Canada

Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula Pingos

The Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula in Canada's Northwest Territories is famous for its many pingos. This area has very old and thick permafrost. The most well-known pingo here is Ibyuk Pingo, which is the tallest in Canada. It's about 50 meters (about 164 feet) above sea level and still grows a few centimeters every year. It's one of the younger pingos in the area, about 1,000 years old. Some larger pingos in this area have started to melt since the 1990s.

Alaska

About 80% of Alaska is covered in permafrost. There are over 1,500 known pingos in Alaska, mostly open-system ones. They range from 3 to 54 meters (about 10 to 177 feet) tall and 15 to 450 meters (about 49 to 1,476 feet) wide. The world's tallest pingo, the Kadleroshilik Pingo, is in Alaska. It's 54 meters (about 177 feet) high and still growing!

Siberia

In Siberia, near the city of Yakutsk on the Lena River, you can find over 500 closed-system pingos. This area has flat plains and thick permafrost, which helps pingos form and grow.

Central Asia

Some pingos in Central Asia are found at the highest elevations in the world. For example, on the Tibetan Plateau, there are pingos above 4,000 meters (about 13,123 feet). The very cold and dry permafrost here is perfect for pingos and helps stop them from collapsing.

Even though Scandinavia is very far north and has permafrost, there are no modern pingos known there. Some low mounds called Palsas have been mistaken for pingos. Some circular lakes and depressions might be what's left of old, collapsed pingos from past cold periods.

Mars

Scientists haven't officially confirmed pingos on Mars. However, they have found features that look very much like pingos. These "pingo-like features" (PLFs) are usually not big enough to be called pingos, or there isn't enough proof yet to classify them as true pingos.

Climate Change and Pingos

Global warming is causing temperatures in the Arctic to rise quickly. This makes permafrost thaw, which is a big problem for places where pingos grow. When permafrost thaws, it can cause the ground to become unstable.

Pingos are very sensitive to changes in the ground because they hold a lot of ice inside. If the permafrost thaws too much, the ice inside pingos can melt. This can cause more pingos to collapse and form new lakes. However, scientists are still studying how climate change will affect the formation and growth of pingos in the future.

See also

In Spanish: Pingo para niños

In Spanish: Pingo para niños

- Gas hydrate pingo - A dome-shaped structure under the sea formed by gas hydrates, similar to a pingo.

- Cryovolcano

- Frost heaving

- Kettle (landform), some are known as pingo ponds.

- Laccolith

- Palsa, a low mound in permafrost areas, often in peat bogs, with an ice lens inside.

- Periglacial lake

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |