Pingualuit crater facts for kids

| New Quebec Crater Chubb Crater |

|

Satellite image of Pingualuit Crater

|

|

| Impact crater/structure | |

|---|---|

| Confidence | confirmed |

| Diameter | 3.44 km (2.14 mi) |

| Depth | 400 m (1,300 ft) |

| Rise | 160 m (520 ft) |

| Age | 1.4 ± 0.1 Ma |

| Exposed | yes |

| Drilled | yes |

| Bolide type | Chondrite |

| Translation | pimple (Inuit) |

| Location | |

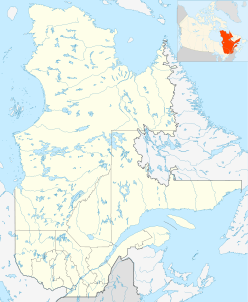

| Coordinates | 61°16′30″N 73°39′37″W / 61.274997°N 73.660278°W |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Quebec |

| District | Nord-du-Québec |

| Municipality | Kativik, Quebec |

The Pingualuit Crater (French: Cratère des Pingualuit) is a special place in Quebec, Canada. Its name comes from the Inuit word for "pimple." It used to be called the "Chubb Crater" and later the "New Quebec Crater."

This crater was made when a space rock, called a meteorite, hit the Earth. It is about 3.44 km (2.14 mi) wide and is estimated to be about 1.4 million years old. Today, the crater and the land around it are part of Pingualuit National Park. Inside the crater is a lake, and the only type of fish living there is the Arctic char.

Contents

Exploring the Crater's Geography

The Pingualuit Crater stands out from the land around it. It rises 160 m (520 ft) above the flat tundra and is 400 m (1,300 ft) deep. A very deep lake, called Pingualuk Lake, fills the bottom of the crater. This lake is 267 m-deep (876 ft), making it one of the deepest lakes in North America.

The water in Pingualuk Lake is incredibly clean and pure. It has very little salt, much less than even the Great Lakes. You can see very far down into the water, sometimes more than 35 m (115 ft) deep! The lake gets its water only from rain and snow, and water leaves only by evaporating into the air. There are no rivers flowing into or out of it.

How the Crater Was Formed

The Pingualuit Crater was created about 1.4 million years ago. This happened when a large meteorite crashed into the Earth. Scientists have studied rocks from the crater to learn about this event.

These rocks show signs of a powerful impact. They also tell us what the meteorite was made of. It seems the meteorite was a type called a Chondrite, which is a common kind of stony meteorite.

Discovery and Scientific Studies

For a long time, only the local Inuit people knew about this amazing lake-filled crater. They called it the "Crystal Eye of Nunavik" because of its clear water. During World War II, pilots flying over the area even used the crater's perfect round shape to help them navigate.

Early Discoveries and Expeditions

In 1943, a United States Air Force plane took a photo that showed the crater's wide rim. Later, in 1948, the Royal Canadian Air Force also took pictures of the area. These photos became public in 1950.

A man named Frederick W. Chubb, who looked for diamonds, saw the strange crater in the photos. He thought it might be an old volcano, which could mean diamonds were nearby. He asked geologist V. Ben Meen from the Royal Ontario Museum for his opinion. Meen thought it was unlikely to be a volcano.

In 1950, Meen and Chubb flew to the crater. Meen suggested calling it "Chubb Crater" and a nearby lake "Museum Lake."

Further Research and Name Changes

Meen then organized a bigger trip in 1951 with the National Geographic Society and the Royal Ontario Museum. They flew in a PBY Catalina flying boat and landed on Museum Lake. They tried to find pieces of the meteorite but couldn't. However, a special tool called a magnetometer found a magnetic spot under the crater's northern edge. This suggested there was a large amount of metal buried there.

Meen led another trip in 1954. That same year, the crater's name was changed to "Cratère du Nouveau-Quebec" (New Quebec Crater).

In 1986, scientists collected more rock samples from the area. These samples showed signs of being changed by a strong impact, which confirmed it was an impact crater. In 1999, the name was changed again to "Pingualuit." On January 1, 2004, the crater and the land around it officially became Pingualuit National Park.

The 2007 Expedition

In 2007, Professor Reinhard Pienitz from Université Laval led a team to the crater. They took long samples of mud from the bottom of the lake. These samples contained tiny fossils of pollen, algae, and insect larvae.

Scientists hoped these fossils would help them learn about how the climate has changed over a very long time, going back to the last warm period between ice ages, about 120,000 years ago. Early results showed that the top part of the mud samples held records of two warm periods.

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |