Poggio Bracciolini facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Poggio Bracciolini

|

|

|---|---|

Engraving of Bracciolini

|

|

| Born |

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini

11 February 1380 Terranuova, Republic of Florence

|

| Died | 30 October 1459 (aged 79) Florence, Republic of Florence

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Papal Secretary |

| Children | 5 sons and a daughter |

Poggio Bracciolini (born Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini; February 11, 1380 – October 30, 1459) was an Italian scholar. He was an important figure in the early Renaissance humanist movement. Poggio is famous for finding and saving many old classical Latin books. These books were often forgotten and decaying in libraries of monasteries in Germany, Switzerland, and France.

Some of his most exciting discoveries include De rerum natura by Lucretius, De architectura by Vitruvius, and several lost speeches by Cicero. He also found Institutio Oratoria by Quintilian and Silvae by Statius. His work helped bring back important ancient knowledge.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Poggio was born near Arezzo in Tuscany, in a village called Terranuova. Later, this village was renamed Terranuova Bracciolini in his honor.

His father took him to Florence because he was very good at studying. There, Poggio learned Latin from Giovanni Malpaghino, a friend of Petrarch. Poggio was very skilled at copying books. This helped him get noticed by important scholars in Florence, like Coluccio Salutati and Niccolò de' Niccoli. He studied law and became a notary at 21.

Career and Adventures

In 1403, Poggio started working for Cardinal Landolfo Maramaldo as his secretary. A few months later, he joined the Pope's office in Rome. He worked for four different popes from 1404 to 1415. He started as a writer of official documents and moved up to become an Apostolicus Secretarius, which means a papal secretary. In this role, he wrote letters for the Pope and took notes. He was known for his excellent Latin and beautiful handwriting.

Poggio worked for seven popes during his 50-year career. Even though he worked for the Church, he remained a layman, meaning he never became a priest. He always saw himself as a Florentine working for the Pope. He stayed in touch with his friends in Florence, including important figures like Leonardo Bruni and Cosimo de' Medici.

Time in England

After a new Pope, Martin V, was chosen in 1417, Poggio traveled with the Pope's court. He then decided to visit England at the invitation of Henry Beaufort, a bishop. He spent five years in England, until 1423. These years were not very productive for him.

Life in Florence

Poggio lived in Florence from 1434 to 1436. He used money from selling a book by Livy to build a villa. He filled his villa with old statues, coins, and inscriptions. His friend Donatello, a famous artist, knew about his collection.

In 1435, at 56 years old, Poggio decided to get married. He married Selvaggia dei Buondelmonti, a young woman from a noble Florentine family who was not yet 18. Despite his friends' worries about the age difference, they had a happy marriage. They had five sons and one daughter. Poggio even wrote a famous dialogue about whether an old man should marry.

He also lived in Florence during the Council of Florence, from 1439 to 1442.

Later Years and Passing

In 1453, Poggio's close friend Carlo Aretino, who was the Chancellor of Florence, passed away. Poggio was chosen to take his place. He decided to leave his job in Rome after 50 years and returned to Florence. This happened around the same time as the fall of Constantinople.

Poggio spent his final years in his new role in Florence. He also worked on his history of Florence. He passed away in 1459 and was buried in the church of Santa Croce. A statue by Donatello and a portrait by Antonio del Pollaiuolo honor him. Poggio was a wealthy man when he died, owning many properties. His wife, five sons, and daughter survived him.

The Search for Old Books

After 1415, the Pope's position was empty for two years. This gave Poggio free time to search for old books. In 1416, he visited a German spa called Baden. He wrote a letter describing the relaxed lifestyle there, even before he found the famous Lucretius book.

Poggio was inspired by earlier Italian humanists like Francesco Petrarch, who had renewed interest in forgotten works. Poggio believed that studying "humanities" (ancient Greek and Latin literature) was very important. He thought it was foolish for leaders to spend time on wars instead of bringing back ancient knowledge.

Poggio was a self-made man who rose from a simple writer to a papal secretary. He was dedicated to bringing back classical studies. He saw many important events, like conflicts between popes and councils.

When he attended the Council of Constance in 1414, he used his free time to explore libraries in Swiss and German monasteries. His greatest discoveries happened between 1415 and 1417. He found many lost Latin masterpieces in places like Reichenau, Weingarten, and especially St. Gall. These finds gave scholars access to texts that were previously lost or only available in damaged copies.

Discoveries at St. Gallen

In his letters, Poggio described finding Cicero's Pro Sexto Roscio, Quintilian, and Statius' Silvae at St. Gallen. He also found Punica by Silius Italicus, Astronomica by Marcus Manilius, and De architectura by Vitruvius. These books were then copied and shared with other scholars. He continued his search in many countries in Western Europe.

Cluny Abbey and Langres

In 1415, at Cluny, he found all of Cicero's great speeches, which had only been partly available before. In 1417, at Langres, he discovered nine more unknown speeches by Cicero.

Monte Cassino and Hersfeld Abbey

At Monte Cassino in 1429, he found a book by Frontinus about the ancient aqueducts of Rome. He also found works by Ammianus Marcellinus, Nonius Marcellus, and others. If he couldn't get a book fairly, he sometimes used tricks. For example, he once bribed a monk to get a Livy and an Ammianus from the library of Hersfeld Abbey.

De rerum natura

Poggio's most famous discovery was the only known copy of Lucretius's De rerum natura ("On the Nature of Things"). He found it in a German monastery (likely Fulda) in January 1417. This was a long Latin poem describing the world as seen by the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus.

The original manuscript Poggio found is now lost. However, he sent a copy to his friend Niccolò de' Niccoli, who made another copy in his famous handwriting. This copy became the basis for over fifty other copies. The book was first printed in 1473.

The 2011 book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt tells the story of Poggio's discovery of the Lucretius manuscript. It explains how this poem influenced the Renaissance and modern science.

Friends and Connections

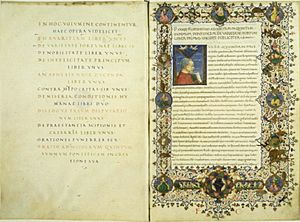

Poggio had close friendships with many important scholars of his time. These included Niccolò de' Niccoli (who helped create the italic script), Leonardo Bruni, Lorenzo and Cosimo de' Medici, and Guarino Veronese. They all shared his passion for finding ancient books and art.

His early friendship with Tommaso da Sarzana was very helpful when his friend became Pope Nicholas V (1447–1455). Pope Nicholas V was a great supporter of scholars and founded the Vatican library in 1448.

These scholars kept in touch through many letters. They wanted to bring back intellectual life to Italy by reconnecting with ancient texts. Their ideas were key to the Humanist Movement in the early Italian Renaissance, which later spread across Europe and led to the full Renaissance.

Poggio's Impact

Poggio was a great traveler. He wrote interesting notes about the customs of England and Switzerland. He also made valuable observations about the ancient ruins in Rome. He wrote a striking description of Jerome of Prague during his trial.

Poggio was a skilled writer in many areas. He wrote speeches, essays, and even funny stories in Latin. He also translated works from Greek.

His Writings

Poggio wrote several important essays in Latin. These essays explored the ideas and values of his time:

- De avaritia (On Greed, 1428−29): This was Poggio's first major work. It discussed wealth and its social importance, showing new ideas about money in Florence.

- An seni sit uxor ducenda (On Marriage in Old Age, 1436): This essay discussed his own decision to marry later in life.

- De nobilitate (On Nobility, 1440): Poggio, who came from a humble background, argued that true nobility comes from good character, not just birth.

- De varietate fortunae (On the Vicissitudes of Fortune, 1447): This work included an account of the Venetian traveler Niccolo de' Conti's journey to Persia and India.

- De miseria humanae conditionis (On the Misery of Human Life, 1455): These were his thoughts after the fall of Constantinople.

These writings, often in the form of dialogues, made Poggio famous. They show his deep knowledge and understanding of his era. He often compared ancient Roman customs with modern ones, or Italian ways with English ways.

Poggio's Historia Florentina (History of Florence) tells the story of Florence from 1350 to 1455. He tried to write it like the ancient historians Livy and Sallust. Poggio focused on wars and how Florence protected itself and Italian freedom. His history is known for its lively storytelling and clear descriptions of people.

His Liber Facetiarum (1438−1452), also called Facetiae, is a collection of funny and sometimes rude stories. It is famous for making fun of monks and priests. This book became very popular across Europe.

Poggio's Epistolae (letters) are also very important. They show his talent as a chronicler of events and his sharp critical mind.

Latin and Greek Revival

Like many humanists, Poggio preferred to write in Latin and translated Greek works into Latin. His letters are full of learning and humor. He was admired for his classical Latin style, which was inspired by Cicero. His writing was considered excellent for his time, especially as Latin was just being revived from a less refined state.

Poggio started learning Greek in 1424, when he was 44. While his Greek was not as strong as his Latin, he did translate Xenophon's Cyropaedia and Lucian's Ass into Latin.

Debates and Arguments

Poggio was known for his strong and sarcastic arguments, called "invectives." These were a special type of writing during the Renaissance used to insult opponents. Poggio used his wide vocabulary to attack the character of his targets, often making outrageous accusations. His most famous arguments were with scholars like George of Trebizond and Antonio Beccadelli.

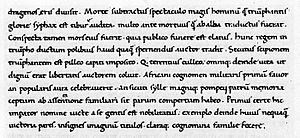

Humanist Script

Poggio was famous for his beautiful and easy-to-read handwriting. Some scholars believe he helped develop the "Humanist minuscule" script, which later led to the "Roman type" font we still use today. While he might not have invented it, he was one of the most important scribes to use it early on, helping it spread throughout Italy.

Works

- Poggii Florentini oratoris et philosophi Opera (1538)

- Poggius Bracciolini Opera Omnia (1964–1969)

- Epistolae (Letters)

- The Facetiae (English translations available)

- Two Renaissance Book Hunters: The Letters of Poggius Bracciolini to Nicolaus De Niccolis (1974)

See also

In Spanish: Poggio Bracciolini para niños

In Spanish: Poggio Bracciolini para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |