Regina Jonas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Regina Jonas |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Religion | Judaism |

| Alma mater | Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums, Berlin |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | German |

| Born | Regine Jonas 3 August 1902 Mitte, Berlin, German Empire |

| Died | 12 October or 12 December 1944 (aged 42) Auschwitz-Birkenau, Auschwitz, Kraków District, German-occupied Poland |

| Parents | Wolf Jonas Sara Jonas (née Hess) |

| Signature |  |

| Semicha | December 27, 1935 |

Regina Jonas (German: Regine Jonas; born August 3, 1902 – died October 12 or December 12, 1944) was a Jewish leader born in Berlin, Germany. She became the first woman ever to be officially ordained as a rabbi in 1935. Her life was a journey of dedication to her faith and community, even during very difficult times.

Contents

Becoming the First Woman Rabbi

Regina Jonas grew up in a very religious family in Berlin. Her father, who was likely her first teacher, passed away when she was 13 years old. Like many young women of her time, she first thought about becoming a teacher.

Studying to Be a Rabbi

After finishing school, Regina decided to study at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in Berlin. She took many courses to become a liberal rabbi and educator. Even though other women attended the university, Regina was different because she openly stated her goal: to become a rabbi.

To achieve this, Jonas wrote a special paper, which was needed for ordination. Her paper was titled "Can a Woman Be a Rabbi According to Halachic Sources?" Halakha means Jewish law. After studying many Jewish texts, she concluded that yes, a woman could be ordained.

The professor in charge of ordinations agreed with her paper. However, he suddenly passed away, which stopped her from getting an official ordination at that time. Regina graduated in 1930, but her diploma only called her an "Academic Teacher of Religion."

Facing Challenges and Achieving Ordination

Regina then asked Rabbi Leo Baeck, a very important Jewish leader in Germany, for his help. Rabbi Baeck had taught her at the seminary. He recognized her as a "thinking and agile preacher" but worried that ordaining a woman would cause problems with other Jewish groups.

For almost five years, Regina taught religious studies in schools. She also gave many unofficial sermons and lectures. She often talked about how important women were in Judaism. Her work caught the attention of Rabbi Max Dienemann, a leader of liberal rabbis.

Despite some protests, Rabbi Dienemann decided to test Regina. On December 27, 1935, Regina Jonas received her semicha, which is the official ordination to become a rabbi. This made her the first woman to be ordained as a rabbi in history.

Life After Ordination

Even after her ordination, the Jewish community in Berlin was not very welcoming. She tried to find work at the New Synagogue but was turned away. Since she couldn't find a position in Berlin, she looked elsewhere.

She found support from the Women's International Zionist Organization. This group helped her work as a chaplain in different Jewish social places. In 1938, she wrote a letter to a Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, saying she was interested in moving to Palestine to find rabbinical opportunities there.

Life During Difficult Times

As Nazi persecution grew, many rabbis left Germany. This left many small Jewish communities without spiritual leaders. Regina Jonas, perhaps to stay with her elderly mother, chose to remain in Nazi Germany.

Continuing Her Work in Germany

The Jewish organization in Germany allowed Jonas to travel to different areas to continue her preaching. However, life for Jewish people under the Nazi government quickly became much worse. Even if a synagogue wanted to host her, the harsh conditions made it impossible to hold services in a proper house of worship.

Despite these challenges, she kept doing her rabbinical work. She continued teaching and holding informal services wherever she could.

Deportation and Life in Theresienstadt

On November 4, 1942, Regina Jonas had to list all her belongings, including her books. Two days later, everything she owned was taken away by the government. The next day, she was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to Theresienstadt.

While she was held in Theresienstadt, she continued her work as a rabbi. A famous psychologist named Viktor Frankl asked for her help. She helped him create a program to prevent people from attempting to end their lives in the camp. Her job was to meet new arrivals at the train station. She would ask them questions about their feelings to help those who were disoriented or struggling.

Regina Jonas worked in the Theresienstadt camp for two years. We still have records of about 23 sermons she wrote there. One was titled What Is Power Nowdays - Jewish Religion, the Power Source for Our Ego Ethics and Religion. During her time there, she also helped organize concerts, lectures, and other performances to help people cope with the terrible situation around them.

The Final Journey

After a brief period of relative calm in the summer of 1944, most of the Jewish leaders in Theresienstadt, including Regina Jonas, were sent to Auschwitz in mid-October 1944. She was tragically killed there, either within a day or two months later. She was 42 years old.

Sadly, many people who lectured in Theresienstadt, including Viktor Frankl and Leo Baeck, never mentioned her name or her important work after the war.

Rediscovering Her Story

For many years, Regina Jonas's story was largely forgotten.

Early Mentions

After Rabbi Sally Priesand was ordained in 1972, an American newspaper reported in 1973 that the only other known Jewish woman to be ordained was Regina Jonas of Berlin. Her thesis title, "Can a Woman Become a Rabbi?", was also mentioned.

Pnina Navè Levinson, who was one of Jonas's students, wrote about her in papers in 1981 and 1986. Levinson noted that important people who were in Theresienstadt with Jonas never spoke about her story. Robert Gordis also briefly discussed Jonas in a 1984 paper, calling her an early example of a woman becoming a rabbi.

The Key Discovery

Regina Jonas's writings and personal items were truly rediscovered in 1991. Dr. Katharina von Kellenbach, a German researcher, found them. She was looking for information about how religious groups in 1930s Germany felt about women becoming religious leaders.

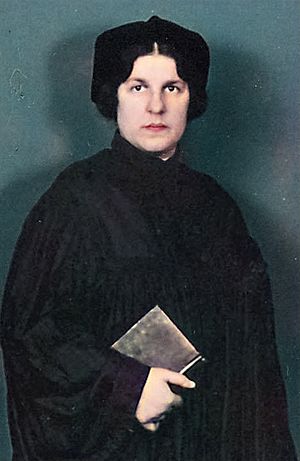

In an archive in East Berlin, she found an envelope. It contained the only two known photos of Regina Jonas, along with her rabbinical diploma, teaching certificate, and other personal papers. These documents became available because the Soviet Union had fallen, and archives in eastern Germany were opened. Thanks to Dr. von Kellenbach's discovery, Regina Jonas is now widely known and remembered.

Sharing Her Life Story

In 1999, Elisa Klapheck published a biography about Regina Jonas. It also included a detailed version of Jonas's thesis, "Can Women Serve as Rabbis?". The biography was translated into English in 2004 as Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas – The Story of the First Woman Rabbi. This book shared stories from people who knew Regina Jonas personally in Berlin or Theresienstadt. Klapheck also wrote about Jonas's relationship with Rabbi Josef Norden.

Her Lasting Impact

While some women before Jonas made important contributions to Jewish thought, like the Maiden of Ludmir or Asenath Barzani, Regina Jonas was the first woman in Jewish history to officially become a rabbi.

Her Teachings and Memorials

A handwritten list of 24 of her lectures, titled "Lectures of the One and Only Woman Rabbi, Regina Jonas," still exists in the Theresienstadt archives. These lectures covered topics like the history of Jewish women, Jewish law, biblical themes, and general introductions to Jewish beliefs and holidays.

A large picture of Regina Jonas was put on a special display in Hackescher Market in Berlin. This was part of a city-wide exhibition called “Diversity Destroyed: Berlin 1933–1938–1945.” It remembered the 80th anniversary of the Nazis coming to power and the 75th anniversary of the November pogrom (a violent attack against Jews).

In 2001, a memorial plaque was placed at Jonas’s former home in Berlin-Mitte. This was done during a conference for European women rabbis and scholars.

Continuing Her Legacy

In 1995, Bea Wyler became the first female rabbi to serve in Germany after World War II. She served in the city of Oldenburg.

In 2010, Alina Treiger became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Germany since Regina Jonas. In 2011, Antje Deusel became the first German-born woman to be ordained as a rabbi in Germany since the Nazi era.

Art and Commemoration

In 2013, a documentary film called Regina premiered. This film, made by British, Hungarian, and German teams, tells the story of Jonas's struggle to become ordained and her relationship with Rabbi Josef Norden.

In 2014, a special opera also titled "Regina" premiered in Canada. It was about Jonas's life and how her forgotten story was later discovered.

On October 17, 2014, Jewish communities across America remembered Regina Jonas on her yahrzeit (the anniversary of her death). Also in 2014, a memorial plaque for Regina Jonas was put up at the former Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic, where she had worked for two years.

In 2015, two Jewish colleges in Germany held an international conference. It was called "The Role of Women’s Leadership in Faith Communities" and marked the 80th anniversary of Regina Jonas’s ordination.

In 2017, Nitzan Stein Kokin, a German woman, became the first person to graduate from Zecharias Frankel College in Germany. This also made her the first Conservative rabbi to be ordained in Germany since before World War II.

See also

In Spanish: Regina Jonas para niños

In Spanish: Regina Jonas para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |