Revolt of the Languedoc winegrowers facts for kids

The Revolt of the Languedoc winegrowers was a big protest movement in 1907. It happened in the Languedoc and Pyrénées-Orientales regions of France. The government, led by Georges Clemenceau, stopped the protests.

This revolt happened because of a big problem in winemaking. Wine prices were falling, and many people were struggling. The movement was also called the "paupers revolt" of the Midi. A famous moment was when soldiers from the 17th infantry regiment joined the protesters in Béziers.

Contents

Why the Revolt Happened

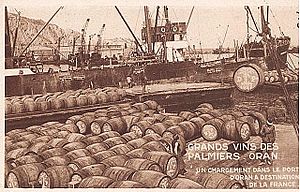

In 1907, winemakers in Languedoc faced a serious crisis. They felt threatened by wines coming from Algeria through the port of Sète. They were also worried about a practice called chaptalization. This is when sugar is added to grape juice before it ferments to make more alcohol.

The problem had been growing for three years. Winemakers could not sell their wine, and many people lost their jobs. Everyone in the region was in distress.

The government allowed Algerian wines to be imported and mixed with French wines. This created too much wine in the market. It caused wine prices to drop a lot in Languedoc-Roussillon.

There was a lot of local wine, plus fake wines and mixed wines. This flooded the market. More wine was imported in 1907, making the problem even worse.

This led to falling prices and a big economic crisis. Small wine growers lost everything, and farm workers became unemployed. This affected everyone, including shopkeepers. The whole region was in misery, and the 1906 wine harvest did not sell.

In February 1907, a tax strike started in Baixas. Joseph Tarrius, a winemaker, created a petition. It said the town could not pay taxes because of the crisis.

Argeliers Committee Forms

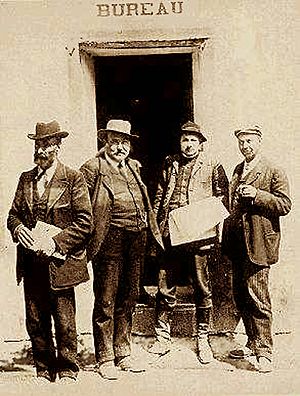

On March 11, 1907, the revolt officially began. A group of winemakers in Minervois, from the village of Argeliers, started it. They were led by Marcelin Albert and Elie Bernard.

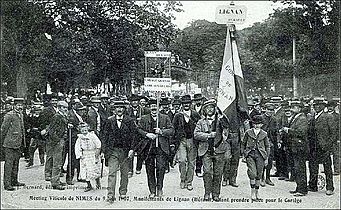

They formed the Committee of Viticulture Defense, also known as the Argeliers Committee. They organized a march of 87 winemakers to Narbonne. There, they spoke to a group of lawmakers.

After their meeting, the committee walked through the city. They sang La Vigneronne for the first time. This song became the anthem of the revolt. The committee included Marcelin Albert as President and Édouard Bourges as Vice-President.

Albert Sarraut, a senator from Aude, tried to help the winemakers. But Georges Clemenceau, the head of the government, did not take the problem seriously. He thought it would just end with a party.

At first, no famous politicians joined the committee. This allowed Marcelin Albert to focus only on fair prices for natural wines. He did not want to get involved in other political issues.

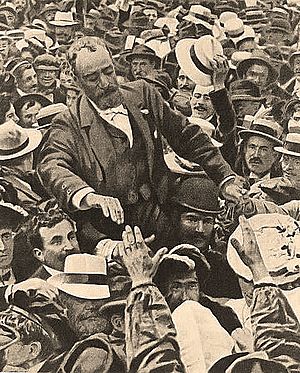

On March 24, the Argeliers Committee held its first meeting in Sallèles-d'Aude. About 300 people attended. Marcelin Albert was a great speaker. He became known as the "apostle" or "redeemer" for the winemakers. They decided to hold a meeting every Sunday in a different city.

Big Demonstrations Start

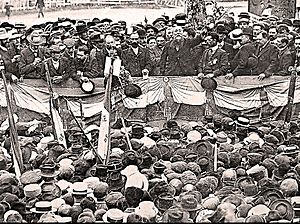

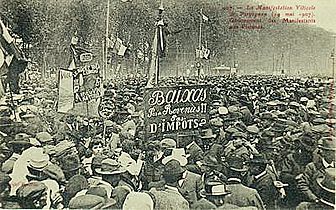

The movement grew bigger and bigger. Rallies were held every Sunday. Tens of thousands of people joined. The protests kept growing until June 9, 1907.

On June 2, 1907, a huge protest happened in Nîmes. Between 250,000 and 300,000 protesters arrived by special trains. A local candy maker showed support by putting a sign on his shop. It said, "Grapes for wine, sugar for candy!"

Montpellier Protest

On June 9, 1907, a massive gathering in Montpellier was the peak of the revolt. The Place de la Comédie was filled with 600,000 to 800,000 people.

Lower Languedoc had about a million people then. This meant almost half the population was protesting. People from different political groups, both left and right, joined together. This was the largest protest in the history of the French Third Republic.

Ernest Ferroul, the mayor of Narbonne, spoke at the rally. He asked all mayors in Languedoc-Roussillon to resign. He openly called for people to disobey the government. Marcelin Albert also gave a powerful speech.

The Catholic Church even helped the protesters. A bishop said that women, children, and striking winemakers could stay in churches overnight. On the same day, about 50,000 people in Algiers protested to support the French winemakers.

A rumor spread that the army was coming. A law student, Pierre Le Roy de Boiseaumarié, set fire to the courthouse door in Montpellier. He wanted to stop soldiers inside from shooting at the protesters.

The government's deadline for the protesters passed on June 10. Clemenceau expected the revolt to be weak. But Ernest Ferroul decided to resign as mayor of Narbonne. He announced it to 10,000 people. He said, "Citizens, I got my power from you, I give it back! The municipal strike begins."

This action was followed by 442 towns in Languedoc Roussillon. Their mayors resigned that week. Black flags were put on town halls. People declared "civic disobedience," meaning they would not follow government rules. Clashes between protesters and police became common.

On June 11, Jean Jaurès, a socialist leader, spoke up for the winemakers in Parliament. He suggested the government take over the wine estates. Clemenceau sent a harsh letter to the mayors. Ernest Ferroul replied, saying Clemenceau did not understand them.

Clemenceau then asked Albert Sarraut to talk with Ferroul. But Ferroul refused. He said, "When we have three million men behind us, we do not negotiate."

Stopping the Revolt

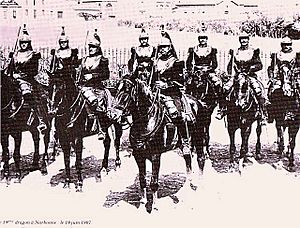

Until then, the Sunday protests had been peaceful. But Clemenceau decided the law needed to show its power. He sent the army to restore order. By June 17, 1907, 22 infantry regiments and 12 cavalry regiments were in the Midi region. This was 25,000 foot soldiers and 8,000 horsemen.

The police were ordered to arrest the protest leaders. Sarraut disagreed with this and resigned from the government. On June 19, Ernest Ferroul was arrested at his home in Narbonne. He was taken to Montpellier. Three other committee members gave themselves up.

News of the arrests made the crowd furious. People lay on the ground to stop the police. Narbonne was like a war zone. A protest started to free the leaders. There were fights all day. The local government building was attacked, and barricades blocked streets.

In the evening, cavalry soldiers fired into the crowd. Two people died, including a 14-year-old. Marcelin Albert, who was not arrested, hid. A new defense committee was formed, led by Louis Blanc.

In many towns, local councils resigned. Up to 600 council members quit. Some called for a tax strike. The situation became very tense. Angry winemakers attacked official buildings.

The next day, June 20, the Midi region exploded. In Perpignan, the local government building was looted and burned. In Montpellier, the crowd fought with soldiers. In Narbonne, a police inspector was attacked. Soldiers were ordered to fire on the protesters.

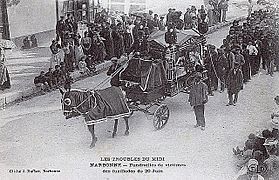

Five people were killed, including a 20-year-old girl named Julie Bourrel. About 33 people were injured. In a café, a worker named Louis Ramon died.

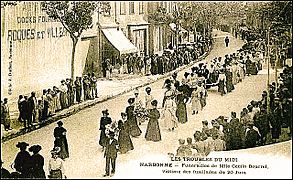

On June 22, 1907, 10,000 people attended Julie Bourrel's funeral in Narbonne. This was the last big protest of the Midi winemakers. Parliament supported the government's actions.

Remembering the Revolt

The 100th anniversary of the 1907 winemakers' revolt was celebrated in 2007. Many exhibitions and cultural events took place. These were held in Aude, including Argeliers, where the movement began. Events also happened in Gard, Pyrénées Orientales, and Herault.

At the Museum of Cruzy, four banners from the 1907 events are displayed. They are now protected as Historical Monuments.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de los viticultores de Languedoc para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de los viticultores de Languedoc para niños