Rhoticity in English facts for kids

Rhoticity in English is a fancy word for how people pronounce the "R" sound in English. Imagine saying the word "farmer." Do you clearly hear the "r" sound at the end? Or does it sound more like "fah-muh"? This difference is what rhoticity is all about!

In rhotic varieties of English, speakers always pronounce the "R" sound, no matter where it is in a word. For example, in words like "hard" or "butter," you'd hear the "R" clearly. This is how most people in the United States, Canada, Scotland, and Ireland speak.

In non-rhotic varieties, speakers often "drop" or don't pronounce the "R" sound when it comes after a vowel and isn't followed by another vowel. So, "hard" might sound like "hahd," and "butter" might sound like "buttah." This is common in most parts of England, Wales, Australia, and New Zealand.

Sometimes, even non-rhotic speakers will pronounce the "R" if the next word starts with a vowel. For example, in "better apples," the "R" in "better" might be pronounced because "apples" starts with a vowel. This is called "linking R."

Contents

How Did Rhoticity Change Over Time?

The way people pronounce the "R" sound has changed a lot over hundreds of years. It wasn't always the same everywhere!

England's "R" Sound History

The "R" sound started to disappear in some parts of England around the 1400s. At first, it was only in a few words and mostly in private writings. By the mid-1700s, people in London, especially those who were well-educated, started dropping the "R" sound more often after vowels.

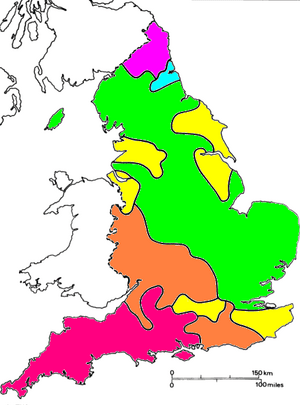

By the early 1800s, the standard way of speaking in southern England had become mostly non-rhotic. This means that people there generally didn't pronounce the "R" after vowels. However, some areas in England, like the West Country (south-west England), parts of Lancashire, and Yorkshire, kept their rhotic accents. Even in the 1950s and 60s, surveys found rhotic accents in many parts of England, but they have become less common since then.

The "R" Sound in the United States

In the 1700s, the way people spoke in British port cities influenced some American cities like New York City and Boston. This caused upper-class people in these American cities to also become non-rhotic, meaning they dropped their "R"s.

However, most of the United States stayed rhotic. After the American Civil War (1861-1865), the centers of power and wealth in America shifted to areas where people pronounced their "R"s. This made rhotic speech more popular and respected across the country. By the mid-1900s, especially after World War II, rhotic speech became the standard for radio and television in the U.S.

Today, most American English is rhotic. But you can still find non-rhotic accents in some older speakers in the American South, and in places like New York City and Boston, though these accents are changing. African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) is also largely non-rhotic.

Where is Rhoticity Found Today?

The way people pronounce the "R" sound helps us tell different English accents apart around the world.

Rhotic Accents

- Most of American English

- Most of Canadian English

- Most of Scottish English

- Most of Irish English

- Philippine English

- Barbadian English

Non-Rhotic Accents

- Most of English English

- Welsh English

- Australian English

- New Zealand English

- South African English

- Nigerian English

- Trinidadian and Tobagonian English

- Standard Malaysian English

- Singaporean English

Mixed or Changing Accents

Some accents are "variably rhotic," meaning speakers might sometimes pronounce the "R" and sometimes not. This can depend on social factors, how formal the situation is, or even the specific words being used. Examples include:

- Much of Indian English

- Pakistani English

- Many Caribbean English accents

- Current New York City English

- Some Southern American English

- Some Eastern New England English

In places like Brunei, the English spoken is becoming more rhotic due to the influence of American English and local languages. In Myanmar, most English speakers are non-rhotic, but some are rhotic.

Even in countries that are mostly non-rhotic, like New Zealand, you can find rhotic accents in specific areas, such as Southland. This is often because of historical influences, like Scottish settlers who spoke rhotic English.

[ə] (non-rhotic) [əʴ] (alveolar) [əʵ] (retroflex) [əʵː] (retroflex & long) [əʶ] (uvular) [ɔʶ] (back & rounded)

Images for kids

-

Red dots show major U.S. cities where the 2006 Atlas of North American English found 50% or higher of non-rhotic speech in at least one white speaker within their data sample. (Non-rhotic speech may be found in speakers of African-American English throughout the country.)

See also

In Spanish: Acento rótico y no rótico para niños

In Spanish: Acento rótico y no rótico para niños

- English-language vowel changes before historic /r/