Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York facts for kids

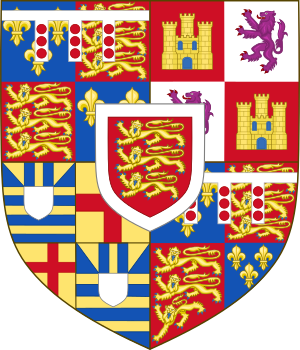

Quick facts for kids Richard of York |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Richard of York in the frontispiece of the Talbot Shrewsbury Book, 1445

|

|

| Born | 21 September 1411 |

| Died | 30 December 1460 (aged 49) Sandal Magna (at the Battle of Wakefield), Yorkshire |

| Burial | 30 July 1476 Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay [Reburial—The original burial was at Pontefract, date unknown, but shortly after his death.] |

| Spouse | Cecily Neville |

| Issue among others |

|

| House | York |

| Father | Richard, Earl of Cambridge |

| Mother | Anne Mortimer |

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (born 21 September 1411 – died 30 December 1460) was a powerful English noble. He was also known as Richard Plantagenet. Richard believed he had a strong claim to the English throne during a time of great trouble called the Wars of the Roses.

He was part of the royal House of Plantagenet. His claim to the throne came from his mother, Anne Mortimer. She was a descendant of King Edward III's second son. The rival House of Lancaster came from Edward III's third son. This made Richard's claim seem stronger to some people.

Richard also inherited huge amounts of land and wealth. He held important jobs in Ireland, France, and England. He even governed England as Lord Protector when King Henry VI became very ill.

His disagreements with King Henry's wife, Margaret of Anjou, and other nobles led to big problems in England. These problems helped start the Wars of the Roses. Richard tried to become king, but he was convinced to wait. It was agreed he would become king after Henry died. However, Richard died in the Battle of Wakefield just weeks after this agreement. Two of his sons, Edward IV and Richard III, later became kings of England.

Contents

- Richard's Family and Claim to the Throne

- Growing Up and Education

- Fighting in France

- Richard's Role in English Politics (Before 1450)

- Richard's Opposition (1450–1453)

- Lord Protector of England (1453–1455)

- Conflict and Its Aftermath (1455–1456)

- An Unstable Peace (1456–1459)

- Civil War Begins (1459)

- A Turn of Events (1459–1460)

- Final Battle and Death

- Richard's Legacy

- Important Jobs Richard Held

- Richard's Children

- Images for kids

Richard's Family and Claim to the Throne

Richard of York was born on 22 September 1411. His parents were Richard, Earl of Cambridge and Anne Mortimer. Both his parents were related to King Edward III of England.

His father was the son of Edmund, 1st Duke of York, Edward III's fourth son. His mother, Anne Mortimer, was a great-granddaughter of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, Edward III's second son.

After his mother's brother, Edmund, Earl of March, died without children in 1425, Richard inherited his family's claim to the throne. This claim was seen by many as better than the one held by the ruling House of Lancaster. The Lancasters were descended from John of Gaunt, Edward III's third son.

Richard had one sister, Isabel. His mother, Anne Mortimer, died around the time he was born. His father was executed in 1415 for plotting against King Henry V. A few months later, Richard's uncle, Edward, 2nd Duke of York, died in battle. So, Richard inherited his uncle's title and lands, becoming the 3rd Duke of York.

When his maternal uncle, Edmund Mortimer, died in 1425, Richard also inherited the vast Mortimer family lands. This made him the richest and most powerful noble in England, second only to the king.

Growing Up and Education

When Richard's father died, Richard became a "ward of the crown." This meant the king's officials managed his property because he was an orphan. Even though his father had plotted against the king, Richard was allowed to keep his family's lands.

In 1423, the king sold Richard's guardianship to Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland. Richard grew up in the Neville family home. The Earl of Westmorland had many children. In 1424, he arranged for 13-year-old Richard to marry his 9-year-old daughter, Cecily Neville. They married by October 1429. This marriage connected Richard to many important English noble families.

When Ralph Neville died in 1425, Richard's guardianship passed to his widow, Joan Beaufort. By this time, Richard had inherited even more land from the Mortimer family, making him even wealthier.

As he grew older, Richard became closer to the young King Henry VI. In 1426, he was knighted. He attended King Henry VI's coronation in 1429. In 1430, he served as Constable of England for a duel. He then went to France with Henry and was there for Henry's coronation as King of France in 1431. In 1432, he took full control of his inherited lands. In 1433, he joined the important Order of the Garter.

Fighting in France

As Richard became an adult, England was still fighting the Hundred Years' War with France. In 1436, Richard was chosen to lead the English forces in France. This was his first time commanding an army.

He landed in France in June 1436. Paris had just fallen to the French, so his army went to Rouen instead. Richard worked with other English captains and had some success. He took back many areas in Normandy and brought order to the region. Much of the fighting was led by John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury. Richard also helped stop French advances and recaptured some towns.

However, Richard was not happy with his job. He had to use a lot of his own money to pay his soldiers. He wanted to leave France as soon as his one-year term ended. But he was told to stay until his replacement arrived. He finally returned to England in November 1437. Even though he was a leading noble, he was not included in King Henry VI's Council.

Return to France

King Henry VI asked Richard to return to France in 1440 after peace talks failed. Richard was again made Lieutenant of France. This time, he had more power and was promised an annual income of £20,000. His wife, Duchess Cecily, went with him to Normandy. Their children Edward, Edmund, and Elizabeth were all born in Rouen.

Richard arrived in France in 1441. He tried to relieve the French siege of Pontoise. Even though he couldn't force the French into a big battle, he and Lord Talbot led a clever campaign. They moved their armies across rivers, chasing the French almost to Paris. But Pontoise was eventually captured by the French in September 1441. This was Richard's only military action during his second time in France.

In 1442, Richard continued to defend Normandy. He signed a truce with the Duchess of Burgundy in 1443. This stopped fighting between England and Burgundy for a while. Funding the war was still a problem. Richard didn't receive money from England for a long time.

In 1443, King Henry VI put John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, in charge of a large army. This army was meant for Gascony, but it took away men and resources that Richard needed in Normandy. This made Richard feel that his role in France was being reduced. Somerset's campaign also caused problems with other French nobles, ruining Richard's efforts to form alliances. Somerset's army achieved nothing and he died in 1444. This event might have started Richard's strong dislike for the Beaufort family, which later contributed to the civil war.

Richard's remaining time in France was spent on daily tasks and administration. He met Margaret of Anjou, who was going to marry King Henry VI, in 1445.

Richard's Role in English Politics (Before 1450)

Richard seemed to stay out of English politics before he returned home in 1445. King Henry VI didn't seem eager to give Richard important jobs. Richard was not even invited to the first royal council meeting in 1437.

Richard returned to England in October 1445. He likely expected to be reappointed to his role in France. However, he was seen as being against the king's policies in France. In 1446, the job of Lieutenant of France went to Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset.

During 1446 and 1447, Richard attended meetings of the King's Council and Parliament. But he spent most of his time managing his lands near the Welsh border.

Richard was likely unhappy when the Council gave up the French province of Maine. This was done to extend the truce with France and get a French bride for Henry. Perhaps because of this, Richard was appointed Lieutenant of Ireland in July 1447. This was a logical choice as he had lands in Ireland. But it also kept him away from England and France for ten years.

Richard stayed in England until June 1449 due to personal matters. When he finally went to Ireland, he took his wife Cecily and an army of about 600 men. This suggested he planned to stay for a while. However, he claimed he didn't have enough money to defend English lands there. So, Richard decided to return to England. He was owed a lot of money by the crown, and his own income was falling.

Richard's Opposition (1450–1453)

By 1450, England was in chaos due to military losses and poor government. In January, a bishop was killed. In May, the king's chief advisor was murdered. The House of Commons demanded that the king take back lands and money he had given to his friends.

In June, people in Kent and Sussex rebelled. They were led by Jack Cade, who used the name Mortimer. They took over London and killed the Lord High Treasurer. In August, the last English towns in Normandy fell to the French. Many refugees came back to England.

On 7 September, Richard landed in England. He avoided the king's attempts to stop him. He gathered followers and arrived in London on 27 September. After a tense meeting with the king, Richard continued to gather support. The violence in London was so bad that Somerset, who had returned from France, was put in the Tower of London for his own safety.

Richard publicly said he wanted to reform the government. He demanded that the "traitors" who lost northern France be punished. He also secretly wanted to get rid of Somerset, who was soon released from the Tower. Richard's men attacked Somerset's properties and servants.

Richard and his ally, the Duke of Norfolk, returned to London in November with many armed followers. They tried to pressure Parliament. Richard was given another job, but he still lacked real support outside Parliament and his own men. In December, Parliament chose Richard's chief assistant as its speaker.

In April 1451, Somerset was released from the Tower and given an important job in Calais. One of Richard's advisors was sent to the Tower for suggesting that Richard should be recognized as the heir to the throne. Parliament was then closed. King Henry VI made some reforms, which helped restore order and improve royal finances. Richard, frustrated by his lack of power, went to his home in Ludlow.

In 1452, Richard tried again to gain power. He said he was loyal to the king. His goal was to be recognized as Henry VI's heir, as Henry had no children after seven years of marriage. He also wanted to destroy the Duke of Somerset. Henry might have preferred Somerset to succeed him, as Somerset was also related to the royal family.

Richard gathered men as he marched from Ludlow towards London. But the city gates were closed against him by the king's orders. At Dartford, Richard's army was outnumbered. He only had the support of two nobles. He was forced to make an agreement with Henry. He was allowed to complain about Somerset to the king. But then he was taken to London and held under house arrest for two weeks. He was forced to swear loyalty to the king.

Lord Protector of England (1453–1455)

By the summer of 1453, Richard seemed to have lost his struggle for power. Henry punished Richard's tenants who had been involved in the Dartford incident. The queen, Margaret of Anjou, was pregnant. Even if she lost the baby, there was another possible heir. By July, Richard had lost both of his important jobs.

Then, in August 1453, King Henry VI suffered a severe mental breakdown. This might have been caused by the news of a big defeat in France, which meant England lost its last lands there. Henry became completely unresponsive and couldn't speak. The Council tried to act as if the king would recover quickly. But they eventually had to admit that something needed to be done.

In October, a Great Council was called. Somerset tried to keep Richard out, but Richard, as the most important duke, was included. Somerset's fears were correct. In November, he was sent to the Tower of London.

On 22 March 1454, the Lord Chancellor died. This made it impossible for the government to continue ruling in the king's name. Henry could not even say who should replace him. Despite the queen's opposition, Richard was appointed Lord Protector of the Realm and Chief Councillor on 27 March 1454.

Richard then appointed his brother-in-law, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, as Chancellor. This was important. Henry's efforts in 1453 had tried to stop violence between noble families. These disputes had become focused around a long-standing feud between the Percy and Neville families. Unfortunately for Henry, Somerset (and thus the king) sided with the Percy family. This pushed the Neville family to support Richard. For the first time, Richard had strong support among some nobles.

Conflict and Its Aftermath (1455–1456)

When King Henry recovered in January 1455, he quickly undid Richard's actions. Somerset was released and restored to favor. Richard lost his job as Captain of Calais and as Protector. Salisbury resigned as Chancellor.

Richard, Salisbury, and Salisbury's eldest son, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, felt threatened. A Great Council was called to meet in Leicester, away from Richard's allies in London. Richard and his Neville relatives gathered their armies in the north and near the Welsh border. By the time Somerset realized what was happening, there was no time to raise a large army for the king.

Richard marched his army south. This blocked the way to the Great Council. The disagreement between him and the king about Somerset would now be settled by force. On 22 May, the king and Somerset arrived at St Albans with a small, poorly equipped army. Richard, Warwick, and Salisbury were already there with a larger, better-equipped army. Many of their soldiers had experience fighting on the borders.

The First Battle of St Albans was not a huge battle. Only about 50 men were killed. But among them were important leaders of the Lancastrian side, including Somerset himself. Richard and the Nevilles had succeeded in killing their enemies. Richard also captured the king, which gave him a chance to regain the power he had lost.

It was very important to keep Henry alive. If he died, Richard would not become king. Instead, Henry's two-year-old son, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, would become king. Since Richard had little support among the nobles, he would not be able to control a council led by Queen Margaret.

Richard took the king back to London. Richard and Salisbury rode alongside, and Warwick carried the royal sword in front. On 25 May, Henry received the crown from Richard. This was a clear sign of Richard's power. Richard made himself Constable of England and appointed Warwick as Captain of Calais. Richard's position grew stronger when some nobles agreed to join his government.

For the rest of the summer, Richard held the king captive. When Parliament met again in November, the throne was empty. It was reported that the king was ill again. Richard became Protector once more. He gave up the job when the king recovered in February 1456. But this time, Henry seemed willing to accept that Richard and his supporters would play a major role in the government.

Salisbury and Warwick continued to serve as advisors. Warwick was confirmed as Captain of Calais. In June, Richard was sent north to defend the border against a possible invasion from Scotland. However, the king soon came under the control of Queen Margaret of Anjou. For the rest of his reign, she would control the king.

An Unstable Peace (1456–1459)

Even though Queen Margaret now held the power, her position was not as strong at first. Richard's job as Lieutenant of Ireland was renewed, and he continued to attend Council meetings. However, in August 1456, the court moved to Coventry, which was in the queen's territory.

Richard was viewed with suspicion for three reasons:

- He seemed to threaten the future of the young Prince of Wales.

- He was trying to arrange a marriage for his eldest son into the powerful Burgundian family.

- By supporting the Nevilles, he was involved in the main cause of trouble in the kingdom: the long-standing feud between the Percy and Neville families.

Here, the Nevilles started to lose influence. Salisbury gradually stopped attending Council meetings. When his brother, a bishop, died in 1457, the new appointment was someone close to the queen. The Percy family received more favor at court and in the border conflicts.

Henry tried to make peace between the warring noble families. This effort reached its peak with "The Love Day" on 25 March 1458. However, the lords had already turned London into an armed camp. Their public show of friendship did not seem to last beyond the ceremony.

Civil War Begins (1459)

In June 1459, a Great Council was called to meet in Coventry. Richard, the Nevilles, and some other lords refused to go. They feared that the armed forces gathered the month before were meant to arrest them.

Instead, Richard and Salisbury gathered their own forces. They met Warwick, who had brought his troops from Calais, in Worcester. Parliament was called to meet in Coventry in November, but without Richard and the Nevilles. This meant they were going to be accused of treason.

Richard and his supporters raised their armies. Salisbury defeated a Lancastrian attack at the Battle of Blore Heath on 23 September 1459. Warwick avoided another army and then joined forces with Richard. On 11 October, Richard tried to move south but was forced to go to Ludlow.

On 12 October, at the Battle of Ludford Bridge, Richard faced Henry again. Warwick's troops from Calais refused to fight. The rebels fled. Richard went to Ireland, and Warwick, Salisbury, and Richard's son Edward went to Calais. Richard's wife Cecily and their two younger sons were captured and imprisoned.

A Turn of Events (1459–1460)

Richard's escape to Ireland actually helped him. He was still Lieutenant of Ireland, and attempts to replace him failed. The Irish Parliament supported him, offering military and financial help.

Warwick's return to Calais was also lucky. His control of the English Channel meant that pro-Yorkist messages could be spread across southern England. These messages emphasized loyalty to the king but criticized his "wicked advisors." Warwick's control of Calais was very important to London's wool merchants.

In December 1459, Richard, Warwick, and Salisbury were declared traitors. This meant their lives were at risk, and their lands would go back to the king. Their children would not inherit. This was the worst punishment a noble could face. Richard was now in a similar situation to Henry Bolingbroke (who later became King Henry IV) in 1398. Only a successful invasion of England could restore his fortune.

If the invasion succeeded, Richard had three choices: become Protector again, remove the king's son from the line of succession so Richard would be next, or claim the throne for himself.

On 26 June 1460, Warwick and Salisbury landed in Sandwich. People in Kent joined them. London opened its gates to the Nevilles on 2 July. They marched north and, on 10 July, defeated the royal army at the Battle of Northampton. They captured Henry and brought him back to London.

Richard stayed in Ireland. He did not return to England until 9 September. When he did, he acted like a king. He marched under the arms of his great-great-grandfather and displayed a banner of the English royal coat of arms as he approached London.

A Parliament called for 7 October cancelled all the laws made by the previous Parliament. On 10 October, Richard arrived in London and stayed in the royal palace. He entered Parliament and placed his hand on the empty throne, as if to sit on it. He might have expected the nobles to declare him king. But there was silence. The Archbishop of Canterbury asked if he wished to see the king. Richard replied, "I know of no person in this realm the which oweth not to wait on me, rather than I of him." This proud answer did not impress the nobles.

The next day, Richard formally presented his claim to the crown based on his family right. However, he had little support among his fellow nobles. After weeks of talks, the best outcome was the Act of Accord. This agreement recognized Richard and his heirs as Henry's successors. In October 1460, Parliament also gave Richard special powers to protect the kingdom and made him Lord Protector of England. He was also given the lands and income of the Prince of Wales, but not the title itself. With the king effectively held captive, Richard and Warwick were the real rulers of the country.

Final Battle and Death

While this was happening, nobles loyal to the Lancastrian side were gathering armies in northern England. Richard faced a threat from the Percy family. Queen Margaret of Anjou was also trying to get support from the new King of Scotland.

Richard, Salisbury, and Richard's second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, headed north on 2 December. They arrived at Richard's castle, Sandal Castle, on 21 December. The situation was bad and getting worse. Forces loyal to Henry controlled the city of York. The Lancastrian armies were led by some of Richard's strongest enemies. These included the Duke of Somerset and the Earl of Northumberland, whose fathers had been killed at the Battle of St Albans. Several northern lords were also jealous of Richard's and Salisbury's wealth.

On 30 December, Richard and his forces left Sandal Castle. It's not clear why they did this. Some say they were tricked by the Lancastrian forces. Others say northern lords, whom Richard thought were allies, betrayed him. Or perhaps Richard simply acted too quickly.

The larger Lancastrian army destroyed Richard's army in the Battle of Wakefield. Richard was killed in the battle. There are different stories about how he died. Some say he was knocked off his horse, wounded, and fought to the death. Others say he was captured, given a mocking crown of reeds, and then beheaded.

Edmund of Rutland was caught trying to escape and was executed. Salisbury escaped but was captured and executed the next night.

Richard's remains were later moved to Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay.

Richard's Legacy

Within a few weeks of Richard of York's death, his oldest surviving son was declared King Edward IV. Edward finally put the House of York on the throne after a big victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton.

After a sometimes difficult reign, Edward IV died in 1483. He was succeeded by his 12-year-old son, Edward V. Edward V was then replaced after 86 days by his uncle, Richard's youngest son, Richard III.

Richard of York's grandchildren included Edward V and Elizabeth of York. Elizabeth married Henry VII, who started the Tudor dynasty. She became the mother of Henry VIII. All future English monarchs would come from the line of Henry VII and Elizabeth, meaning they are all descendants of Richard of York himself.

In plays, Richard appears in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 1, Henry VI, Part 2, and Henry VI, Part 3.

Richard of York is also part of a popular saying: "Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain." This helps people remember the colors of a rainbow in order (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet).

Important Jobs Richard Held

- Lieutenant-general and governor of France (1436–1437, 1440–1445)

- Lord Protector of England

- Lieutenant of Ireland

Richard's Children

King of England

Duchess of Suffolk

Duchess of Burgundy

Duke of Clarence

King of England

Richard had twelve children with Cecily Neville. Here are the ones who survived to adulthood:

- Anne of York (1439–1476). She married Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter and later Thomas St. Leger.

- Edward IV of England (1442–1483). He became King of England and married Elizabeth Woodville.

- Elizabeth of York (1444–after 1503). She married John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk.

- Margaret of York (1446–1503). She married Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

- George, Duke of Clarence (1449–1478). He married Lady Isabel Neville.

- Richard III of England (1452–1485). He became King of England and married Lady Anne Neville.

Images for kids