Richard Gwyn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SaintRichard Gwyn |

|

|---|---|

Detail of a painting of Richard Gwyn in Wrexham Cathedral

|

|

| Martyr | |

| Born | ca. 1537 Montgomeryshire, Wales |

| Died | 15 October 1584 (aged 47) Wrexham, Wales |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI |

| Canonized | 25 October 1970 by Pope Paul VI |

| Major shrine | Wrexham Cathedral |

| Feast | 4 May, 25 October |

| Patronage | Latin Mass Society of England and Wales, Roman Catholic Diocese of Wrexham, teachers, large families, parents of large families |

Richard Gwyn (around 1537 – October 15, 1584), also known as Richard White, was a Welsh teacher. He taught at secret schools and was a Bard, writing both Christian and funny poems in the Welsh language. He was a Roman Catholic during the time of Queen Elizabeth I of England. Gwyn was put to death for going against the Queen's laws in Wrexham in 1584.

In 1970, Pope Paul VI made him a saint. He is one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. Since 1987, Saint Richard Gwyn has been the Patron Saint of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wrexham. He is also a co-patron of the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales.

Contents

Richard Gwyn's Early Life

Not much is known about Richard Gwyn's early life. He was born around 1537 in Llanidloes, Montgomeryshire, Wales. Reports say he "came from a good family."

When he was about 20, he decided to study. He went to Oxford University but didn't stay long. Then he went to Cambridge University. There, he was supported by the College and its leader, Dr. George Bullock. During his time at university, other students called him "Richard White." This was the English version of his name.

In the early years of Queen Elizabeth I's rule, Dr. Bullock had to leave his job in July 1559. Because of this, Gwyn also had to leave the college.

Becoming a Teacher

After leaving university, Gwyn needed money. So, he became a teacher before finishing his own studies. He went back to his home area in Wales. Gwyn worked as a schoolmaster in villages near Wrexham. These included Gresford, Yswyd, and Overton-on-Dee. He kept studying subjects like history and theology.

Gwyn married Catherine, a young woman from Overton-on-Dee. They had six children, but only three were still alive when he died.

Standing Up for His Faith

Richard Gwyn was a Recusant. This meant he refused to attend Anglican church services. He also refused to take the Oath of Supremacy. This oath said the Queen was the head of the Church. Even though he faced threats of fines and jail, he stuck to his beliefs.

In his small village, everyone knew he was Catholic. Gwyn also openly told his neighbors to return to the Catholic Church.

At this time, Queen Elizabeth I wanted bishops to arrest Recusants. She especially wanted them to arrest schoolmasters and Welsh Bards. Schoolmasters had a lot of influence. Bards like Richard Gwyn acted as secret messengers. They helped Roman Catholic priests and Recusants among the Welsh nobles. Bards were very important in the secret Welsh Catholic network. They spread news about secret Masses and religious trips.

Because of this, Bishop William Downham started to bother Gwyn. The Bishop wanted Gwyn to attend Anglican services. Gwyn didn't want to, but he finally agreed to go to a service in Overton-on-Dee. The next Sunday, after the service, a group of crows and kites attacked him. They pecked him all the way home.

Soon after, Gwyn became very sick. He thought he might die. He promised God that if he got better, he would return to the Catholic faith. He promised he would never again go to a Protestant church. After this, Catholic priests started arriving in North Wales. Gwyn went to Confession and returned to the religion he grew up with.

Life on the Run

Bishop Downham and the Protestants in Overton were angry that Gwyn returned to Catholicism. They made his life so hard that Gwyn and his family left the area. They walked to Erbistock and found a new home.

In Erbistock, Gwyn started a secret school in an empty barn. It was like an Irish "hedge school." He secretly taught the children of local Catholic families. But soon, Gwyn had to leave Erbistock too, to avoid being arrested.

One night in early 1579, Richard Gwyn was arrested in Wrexham. He was visiting the city's Cattle Market. He was put in Wrexham Jail. He was offered freedom if he would join the official church. He refused. Gwyn was told he would see the judges the next day. But that very night, Gwyn escaped. He stayed hidden for a year and a half.

Richard Gwyn's Imprisonment

After eighteen months of hiding, Gwyn was going to Wrexham in July 1580. He needed to deliver a secret message that a priest was urgently needed. On his way, a rich merchant named David Edwards recognized him. Edwards told Gwyn to stop. When Gwyn refused, Edwards attacked him with a dagger. Gwyn defended himself with his staff and hit Edwards. Edwards fell to the ground. Gwyn ran away. Edwards chased him, shouting, "Stop thief!" Edwards' servants were nearby. They heard him and surrounded Gwyn, catching him.

David Edwards took Gwyn to his house. He kept him there with heavy chains until the judges arrived. The judges took Gwyn to Wrexham prison. He was put in a dark underground cell called "The Black Chamber."

After two days in the cold Black Chamber, Gwyn was brought before a judge. The judge ordered that Gwyn be sent to Ruthin Castle. He was to be "very strictly guarded" because he was suspected of going against the Queen. For his first three months in Ruthin Castle, Gwyn wore heavy chains on his arms and legs. He couldn't even lie on his side to sleep.

At the court session in 1580, Gwyn was offered freedom. He just had to agree to go to Anglican services. He also had to give the names of the Catholic parents whose children he had taught in Erbistock. Gwyn refused and was sent back to Ruthin Castle. However, his jailer realized Gwyn was only a prisoner for his religion. So, the jailer treated him a little less harshly.

Around Christmas 1580, all the prisoners at Ruthin Castle were moved to Wrexham Jail. The new jailer put a large pair of shackles on Gwyn. He had to wear them day and night for the whole next year. When he appeared in court again, Gwyn still refused to change his faith.

Richard Gwyn's Trial

On Friday, October 9, 1584, Richard Gwyn and two other people were brought to court in Wrexham. The judges were led by Sir George Bromley.

The court clerk read the charges. All three prisoners were accused of going against the Queen's laws. This was under the Act of Supremacy. This law said the Queen was the head of the Church. At that time, people accused of this crime in England were not allowed to have a lawyer. They had to speak for themselves.

At 8:00 AM on Saturday, October 10, 1584, the jury gave their decision. Richard Gwyn was found guilty. He was sentenced to death. His execution was set for Thursday, October 15, 1584.

Richard Gwyn: The Bard

When Richard Gwyn started working as a schoolmaster, he was very interested in the Welsh folklore and poetry of the Wrexham area.

At that time, Queen Elizabeth I had ordered that Welsh bards be tested. Only those approved by the Crown could write Welsh poetry or compete in poetry festivals called Eisteddfodau. Poets who were not approved were forced to "do some honest work." But Richard Gwyn chose to write poetry anyway. An old writer from that time said that Gwyn was one of the best in his country at the Welsh tongue. He left behind writings that showed his cleverness, passion, goodness, and learning.

In the early 1900s, five Welsh poems by Saint Richard Gwyn were found. They were in a special old book called the Llanover Manuscripts. The book with the poems was written in 1670. It was in the handwriting of a famous Welsh poet named Gwilym Puw. He was a Catholic noble who fought for the King during the English Civil War. A sixth poem was found in the Cardiff Free Library.

All six of Gwyn's poems were translated into English. They were published side-by-side with the original Welsh in 1908.

In 1931, a Welsh Bard named T.H. Parry-Williams published his own scholarly edition of Richard Gwyn's complete poems. He also included original writings about Gwyn's life in Welsh, English, and Latin.

Becoming a Saint

In 1588, a detailed story of Richard Gwyn's death as a martyr was published. It was written in Latin by Fr. John Bridgewater.

After Catholics were allowed more freedom in 1829, an old handwritten book was found. It was called "A True Report of the Life and Martyrdom of Mr. Richard White, Schoolmaster." This book gave a detailed account of Richard Gwyn's life and death. The book is kept at St. Beuno's College in Wales. Its contents were first published in 1860. This old English account has been found to be more accurate than the Latin one.

Cardinal William Godfrey sent 24 possible miracle cures to the Church. One case was chosen as the clearest: a young mother who was supposedly cured of a serious illness. Since other saints had been made saints without needing a miracle, Pope Paul VI decided that all 40 martyrs could be recognized as saints based on this one miracle.

The ceremony to make St. Richard Gwyn a saint happened in Rome on October 25, 1970. It was part of the ceremony for the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

Feast Day

Like the other 39 martyrs, St. Richard Gwyn was first remembered by the Catholic Church in England on October 25. Now, he is honored with all the other martyrs of the English Reformation on May 4.

The Catholic Church in Wales celebrates the feast day of the Six Welsh Martyrs every year on October 25. This group includes priests and the layman Richard Gwyn.

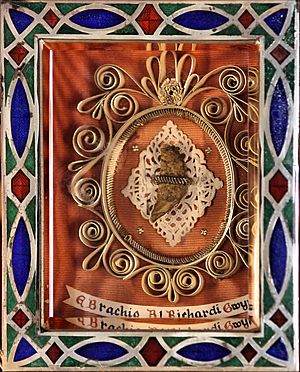

You can see relics of St. Richard Gwyn at the Church of Our Lady of Sorrows in Wrexham. This church started being built in 1857. Every year, Catholics in Wrexham honor St. Richard Gwyn with a procession. They go to the place where he was put to death. Gwyn is also a co-patron of the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales. This group holds a yearly trip to Wrexham and a special Mass near the anniversary of Gwyn's death.

Other relics of St. Richard Gwyn can be found at the Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady and Saint Richard Gwyn in his hometown of Llanidloes. This church was built in the 1950s. The first Mass was held there on October 18, 1959.

Remembering Richard Gwyn

In 1954, Blessed Richard Gwyn Roman Catholic High School was started in Flint, Flintshire. Its name was changed slightly after Gwyn became a saint in 1970. St Richard Gwyn Catholic High School in the Vale of Glamorgan was renamed in honor of St Richard Gwyn in 1987.

A Poem by Richard Gwyn

Here is a small part of a poem by Richard Gwyn, translated from Welsh:

- From Carol IV:

- Nid wrth fwyta cig yn ffêst

- A llenwi'r gêst Wenere

- A throi meddwl gida'r gwynt,

- Yr aethon gynt yn Saintie.

- "People didn't become saints long ago

- By eating meat quickly

- And filling their stomachs on Fridays

- And changing their minds with the wind."

See also

In Spanish: Ricardo Gwyn para niños

In Spanish: Ricardo Gwyn para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |