Robert Morrison (missionary) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Robert Morrison |

|

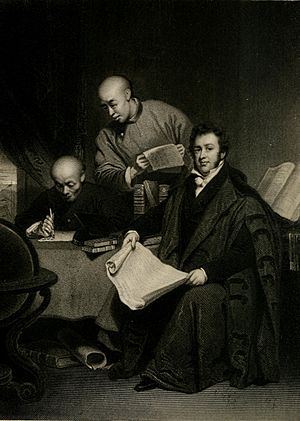

Portrait of Morrison by John Wildman |

|

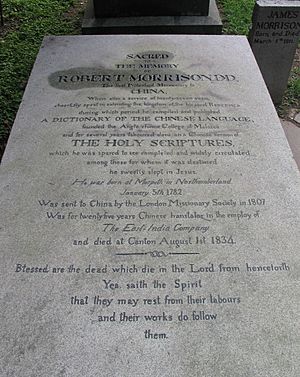

| Born | 5 January 1782 in Morpeth, Northumberland, England |

|---|---|

| Died | 1 August 1834 (aged 52) in Canton, Guangdong, China |

| Title | D.D. |

| Spouse |

Mary Morrison (née Morton)

(m. 1809; died 1821)Eliza Morrison (née Armstrong)

(m. 1824) |

| Children | 8, including John Robert Morrison, George_S._Morrison |

| Parents | James Morrison Hannah Nicholson |

Robert Morrison (born January 5, 1782 – died August 1, 1834) was an important British Protestant missionary. He was the first Protestant missionary to China. He also became a famous expert on China, a dictionary maker, and a translator. Many people call him the "Father of Anglo-Chinese Literature" because of his pioneering work.

Morrison was a Presbyterian minister. He is best known for his work in China, which lasted 25 years. During this time, he translated the entire Bible into Chinese. He also baptized ten Chinese people who became Christians, including Cai Gao, Liang Fa, and Wat Ngong. Morrison was the first to translate the Bible into Chinese and wanted to share it widely. This was different from earlier Catholic translations, which were never published.

He worked with other missionaries like Walter Henry Medhurst and William Milne. He also worked with Samuel Dyer, Karl Gützlaff, and Peter Parker. Morrison spent 27 years in China, with one trip back home to England. At that time, missionaries could only work in Guangzhou (Canton) and Macau. They focused on sharing books and ideas. They helped a few people become Christians and started important work in education and medicine. This work would greatly impact China's culture and history. When Morrison first arrived, someone asked if he expected to make a big spiritual impact. He replied, "No sir, but I expect God will!"

Contents

Robert Morrison: Pioneer Missionary

Early Life and Dreams

Robert Morrison was born on January 5, 1782. His birthplace was Bullers Green, near Morpeth, England. His father, James Morrison, was a Scottish farm worker. His mother, Hannah Nicholson, was English. Both were active members of the Church of Scotland. Robert was the youngest of their eight children. When Robert was three, his family moved to Newcastle. His father found better work there in the shoe business.

Robert's parents were very religious. They taught their children about the Bible and Presbyterian beliefs. When he was 12, Robert could recite the entire 119th Psalm from memory. This psalm has 176 verses! During this time, many new missionary groups were forming.

In 1796, Robert became an apprentice to his uncle, James Nicholson. He joined the Presbyterian church in 1798. At 14, Robert left school to work for his father. He worked long hours, sometimes 12 to 14 hours a day. But he always found time to read and think for an hour or two. He kept a diary, which showed he thought deeply about his life.

Soon, Robert wanted to become a missionary. In 1801, he started learning Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. He also studied theology and shorthand. His parents did not like his new goal at first. Robert often spent time in the garden praying and thinking. At work, he kept his Bible or other books open while he worked. He went to church every Sunday. He also visited sick people with a charity group. In his free time, he taught poor children. He shared his Christian faith with friends and family.

On January 7, 1803, he joined the Hoxton Academy in London. There, he trained to be a Congregationalist minister. He visited the poor and sick and preached in villages near London. By age 17, Morrison was inspired by stories of missionaries. He had promised his mother he would not go abroad while she was alive. He cared for her during her last illness. After she passed away, she gave him her blessing to become a missionary.

Getting Ready for China

After his mother died in 1804, Morrison joined the London Missionary Society. He applied to them on May 27, 1804. The next day, he was interviewed and accepted right away. The following year, he went to David Bogue's Academy for more training. For a while, he thought about going to Africa or China.

Around 1798, a minister named Rev. William Willis Moseley suggested creating a group. This group would translate the Bible into Asian languages. He found a Chinese translation of most of the New Testament in the British Museum. He printed 100 copies of a paper about translating the Bible into Chinese. He sent these to church leaders and mission groups. Most replies were discouraging. They said it would be too expensive and impossible to spread books in China.

But a copy reached Dr. Bogue, the head of Hoxton Academy. He said if he were younger, he would dedicate his life to spreading the Gospel in China. Dr. Bogue promised to find suitable missionaries for China. He chose Morrison, who then focused only on China.

Morrison returned to London to study medicine and astronomy. He worked hard to learn Chinese. He learned from a student named Yong Sam-tak from Canton City. At first, they had trouble. Morrison accidentally burned a paper with Chinese characters. This upset his teacher, who was superstitious. From then on, Morrison wrote characters on a piece of tin that could be erased. They continued to work together. They studied an early Chinese translation of the Gospels and a Latin-Chinese dictionary. Yong Sam-tak even joined Morrison in prayer. Morrison made great progress in speaking and writing Chinese. The mission leaders hoped he would master the language. They wanted him to create a dictionary and translate the Bible. This would help future missionaries.

At that time, foreigners could not easily deal with Chinese people. They were only allowed for trade. Foreigners were questioned strictly upon arrival. Giving the wrong answers could mean being sent away. Morrison knew the dangers. He visited his family in July 1806 to say goodbye. He preached 13 times in London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow.

Arriving in China

Morrison was ordained in London on January 8, 1807. He was eager to go to China. On January 31, he sailed to America first. The British East India Company did not allow missionaries on their ships. There were no other ships going directly to China. So, he had to stop in New York City. Morrison stayed in the United States for almost a month. He wanted to get help from the American Consul in Canton (Guangzhou). He knew he would need someone in authority to be allowed to stay in China. The American consul promised to help him. On May 12, he boarded another ship, the Trident, heading for Macau.

The Trident arrived in Macau on September 4, 1807. Morrison first presented his letters of introduction to British and American leaders in Macau and Canton. They were kind, but they told him about the many difficulties he would face. George Thomas Staunton told him it was almost impossible to be a missionary in China. First, Chinese people were forbidden to teach their language to foreigners. The penalty was death. Second, foreigners could only stay in China for trade. Third, Portuguese Catholic missionaries in Macau would be against a Protestant mission. On September 7, Catholic authorities in Macau made him leave. He then went to the Thirteen Factories outside Guangzhou. The head of the American trading post in Canton offered Morrison a room. He was very grateful to settle there and think about his situation. He later arranged to live at another American's factory for three months. He pretended to be an American. The Chinese did not dislike Americans as much as the British. Still, Morrison's presence caused suspicion. He could not leave his Chinese books out. People might guess he was trying to learn the language. Some Chinese Catholics, like Abel Yun, taught him Mandarin Chinese. But he soon found that Mandarin did not help him understand common people. He had not come to China just to translate for a small group of rich people.

His first few months were very hard. He had to live almost completely alone. He was afraid of being seen outside. His Chinese servants cheated him. The man who taught him Chinese demanded too much money. Another man bought him Chinese books but overcharged him a lot. Morrison was worried about how much money he was spending. He tried living in one room, but he was warned he would get sick. He felt very lonely. The future seemed very bleak.

At first, Morrison tried to act like the local people. He ate local food, learned to use chopsticks, and grew his nails long. He even grew a queue (a traditional Chinese braid). Another missionary, Milne, noted that Morrison wore Chinese clothes and shoes. But over time, Morrison realized this was a mistake. The food made him sick. The Chinese clothes only made him stand out more. He wanted to avoid attention, but dressing like a Chinese person made people more suspicious. They thought he was trying to sneak into Chinese society to spread his religion. So, Morrison went back to dressing and acting like other Europeans.

Morrison's work was also threatened by political problems. England was fighting a war with France. An English navy group came to Macau to stop the French from harming English trade. The Chinese authorities in Guangzhou were angry about this. They threatened to punish the English people living there. Everyone panicked. English families had to go onto ships and sail to Macau. Morrison went with them, taking his important papers and books. The political problem soon passed, and the navy left. But the Chinese became even more suspicious of foreigners.

Working for the East India Company

Morrison became ill and returned to Macau on June 1, 1808. Luckily, he had learned both Mandarin and Cantonese during this time. He found it hard to find a place to live in Macau. He paid a very high price for a small room on the top floor. Soon after, the roof fell in! He would have stayed even then, but his landlord raised the rent, forcing him to leave. He continued to work on his Chinese dictionary. He even prayed in broken Chinese to master the language. He had become so isolated, fearing being ordered to leave, that his health suffered greatly. He could barely walk across his small room. But he kept working.

Morrison tried to connect with the local people. He tried to teach three Chinese boys who lived on the streets. He hoped to help them and improve his language skills. However, they treated him badly, and he had to let them go.

In 1809, he met 17-year-old Mary Morton. They married on February 20 that year in Macau. They had three children: James (who died the same day he was born), Mary Rebecca (1812–1902), and John Robert Morrison (born 1814). Mary Morrison died of cholera on June 10, 1821. She is buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau.

On their wedding day, Robert Morrison was hired as a translator for the British East India Company. He earned £500 a year. He returned to Guangzhou alone because foreign women were not allowed to live there.

This job gave him the security he needed to continue his mission work. He now had a clear job in trade, which did not stop his missionary goals. His daily translation work for the company helped him learn the language better. It also gave him more chances to talk with Chinese people. He could now move around more freely. Businessmen already recognized his skill in Chinese.

The sea between Macau and Canton was full of pirates. The Morrisons had many worrying journeys. Sometimes, alarms would sound even in Guangzhou as pirates came close to the city. The authorities could do little. The dangers and loneliness seemed to affect Mary greatly. She was very anxious. There was no friendly community for them in Guangzhou. The British and American residents were kind, but they did not understand or believe in his work. The Chinese authorities made it difficult to bury their first child. Morrison sadly had to oversee his burial on a mountainside. At that time, his wife was very ill. His colleagues at the company thought he was foolish. His Chinese helpers sometimes stole from him. Letters from England arrived very rarely.

His Chinese grammar book was finished in 1812. It was sent to Bengal for printing. Morrison did not hear about it for three long years. But it was well-received and printed nicely. It was a very important step in helping England and America understand China. Morrison then printed a religious paper and a catechism (a book of questions and answers about faith). He translated the book of Acts into Chinese. He was overcharged for printing a thousand copies. Then Morrison translated the Gospel of Luke and printed it. The Catholic bishop in Macau ordered this book to be burned. He called it a "heretical book" (meaning it went against accepted religious beliefs). So, to common people, it seemed that one group of Christians was destroying what another group produced. This did not look good for Christianity in China.

The Chinese government started to take action when they read some of his printed works. Morrison learned about the trouble when an official order was published. This order was against him and all Europeans who tried to change Chinese religion. It said that printing and publishing Christian books in Chinese was a crime punishable by death. Anyone who wrote such a book would be killed. All his helpers would face severe punishments. Officials were told to find and punish anyone breaking this rule. Morrison sent a translation of this order to England. He also told his mission leaders that he planned to continue his work quietly and firmly. He was not afraid for himself. His job with the East India Company protected him. Also, a grammar book and dictionary were not clearly Christian publications. But the mission leaders were sending Rev. William Milne and his wife to join him. Morrison knew this order would make it very dangerous for another missionary to settle in Guangzhou.

On July 4, 1813, Mr. and Mrs. Morrison were about to take communion in Macau. A note arrived saying that Mr. and Mrs. William Milne had landed. Morrison used all his influence to try and let Milne stay. Five days after the Milnes arrived, a soldier from the Governor came to Morrison's house. He summoned Morrison. The decision was quick and harsh: Milne had to leave in eight days. Not only did the Chinese strongly oppose his stay, but Catholics also pushed for him to be sent away. English residents in Macau did not help Morrison either. They feared that any problems caused by Morrison would hurt their business. For now, Mr. and Mrs. Milne went to Guangzhou. The Morrisons followed them. Soon, both families were settled in that city, waiting to see what the authorities would do next. Morrison spent this time helping Milne learn Chinese.

In 1820, Morrison met American businessman David Olyphant in Canton. This started a long friendship. Olyphant even named his son Robert Morrison Olyphant after him.

A Trip Home and Back to China

In 1822, Morrison visited Malacca and Singapore. He returned to England in 1824. The University of Glasgow had given him a Doctor of Divinity degree in 1817. When he returned to England, Morrison became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He brought a large collection of Chinese books to England. These books were given to the London University College. During his stay, Morrison started "The Language Institution" in London to teach missionaries.

Morrison spent 1824 and 1825 in England. He gave his Chinese Bible to King George IV. People from all parts of society showed him great respect. He taught Chinese to English gentlemen and ladies. He also worked to create interest and support for China. Before returning to his missionary work, he married again in November 1824. His new wife was Eliza Armstrong. They had five more children. His new wife and the children from his first marriage returned to China with him in 1826.

An event during the voyage shows the dangers of those days and Morrison's courage. After a terrible storm, passengers heard the sound of swords and gunshots. They learned that a mutiny had started among the sailors. The sailors were unhappy with their pay. They had taken over the front part of the ship. They planned to turn the cannons against the ship's officers. It was a very dangerous moment. At the height of the panic, Morrison calmly walked among the mutineers. After speaking to them seriously, he convinced most of them to return to their posts. The rest were easily captured.

In Singapore, Morrison faced new challenges. The Singapore Institution, now Raffles Institution, had been started before he left for England. It was similar to the college in Malacca. But little progress had been made. A new governor showed less interest. Morrison had not been there to make sure the work continued. After organizing things there, Morrison and his family went to Macau. Then Morrison went to Guangzhou. He found that his property had also been neglected while he was away.

Final Days in China

The Morrisons returned to China together in 1826. Changes in the East India Company meant he worked with new officials. Some of these officials did not respect missionaries. They tried to be bossy until Morrison threatened to resign. This made them more respectful. Also, relations between British traders and Chinese officials were becoming more tense. Morrison did not like much of the communication he had to handle with Chinese officials. He saw the growing problems in the region. He noted that Chinese officials were often difficult. But Morrison also criticized the behavior of British traders. This behavior threatened the work of Christian missionaries in China. He noticed that foreign trade was more important than missionary activities.

When Morrison visited England, he left a Chinese teacher named Liang Fa in China. Liang Fa was one of Milne's converts. He continued the work among the people. This man had suffered a lot for his faith. He remained strong and dedicated during Morrison's long absence. Other Chinese Christians were baptized. The small church grew. Many people believed in secret but were afraid to openly declare their faith. American missionaries came to help Morrison. More Christian books were published. Morrison welcomed the Americans. They could lead services for English residents. This freed him to preach and talk to Chinese people who gathered to hear the Gospel.

The Catholic bishop again opposed Morrison in 1833. This led to his printing presses in Macau being shut down. This was his main way of sharing Christian knowledge. However, his Chinese helpers continued to share books that had already been printed. During this time, Morrison also wrote for Karl Gützlaff's Eastern Western Monthly Magazine. This magazine aimed to improve understanding between China and the West.

In 1834, the East India Company's special trading rights with China ended. Morrison's job with the company was removed. He lost his income. He was then appointed a government translator under Lord Napier. But he only held this job for a few days.

Morrison prepared his last sermon in June 1834. He was becoming very ill. He felt very lonely because his wife and family had been sent to England. On August 1, the first Protestant missionary to China died. He passed away at his home in Canton (Guangzhou) at age 52, in his son's arms. The next day, his body was moved to Macau. He was buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery on August 5. He was buried next to his first wife and child. He left behind seven children: two from his first wife (Mary Rebecca and John Robert) and five from his second wife, Eliza. His oldest daughter, Mary Rebecca (1812–1902), married Benjamin Hobson, a medical missionary, in 1847.

Legacy and Honours

Morrison had collected "the most complete library of Chinese literature in Europe." This collection formed the basis of his Language Institution in London. His widow offered all 900 books for sale in 1837 for £2,000.

The Morrison Hill area in Hong Kong and its nearby road, Morrison Hill Road, are named after him. The Morrison School, built on this hill by the Morrison Education Society, was completed shortly after Morrison's death in 1843. The Morrison Hill Swimming Pool is a public swimming pool in Hong Kong today.

The University of Hong Kong's Morrison Hall, started in 1913, was a Christian dorm for Chinese students. It was named after Morrison by its supporters, the London Missionary Society.

Morrison House at YMCA of Hong Kong Christian College is named in his memory. Morrison House at Raffles Institution in Singapore is also named after him.

Morrison Building is a protected historical building in Hong Kong. It was the oldest building in the Hoh Fuk Tong Centre in Tuen Mun, New Territories.

Morrison Academy is an international Christian school in Taichung, Taiwan.

An engraving of a painting by George Chinnery shows Li Shigong and Chen Laoyi translating the Bible with Morrison watching. This image was published in 1838 with a poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon.

Missionary Work

Morrison created a Chinese translation of the Bible. He also put together a Chinese dictionary for Westerners to use. The Bible translation took him twelve years. The dictionary took sixteen years to complete. During this time, in 1815, he left his job with the East India Company.

By the end of 1813, the entire New Testament translation was finished and printed. Morrison knew it wasn't perfect. But he said it was a translation into the real, everyday Chinese language, not a formal, old-fashioned one. Having many printed copies led the two missionaries to plan how to share them widely.

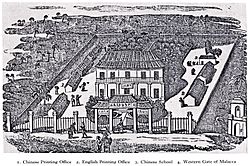

At this time, parts of the Malay Peninsula were under British control. British governors lived there. This seemed like a good place to set up a mission station. The station would be close to the Chinese coast. Chinese missionaries could be trained there. They might enter China without causing as much suspicion as English people. The two main places considered were the island of Java and Malacca on the Malay Peninsula.

Many thousands of Chinese people lived in these areas. Milne traveled around, exploring the country and giving out religious papers and New Testaments. The missionaries wanted to find a quiet place. There, under protection, they could set up a printing press. They also wanted to train Chinese missionaries. Malacca was a good choice because it was between India and China. It had ways to transport materials to almost any part of China and nearby islands. After much thought, they decided Milne should go to Malacca.

In this year, Morrison baptized his first convert on May 14, 1814. This was seven years after he arrived. The first Protestant Chinese Christian was likely named Cai Gao. Morrison knew this man's understanding was not perfect. He did not mention his role in Cai's baptism until much later. But he relied on the words, "If thou believest with all thy heart!" and performed the baptism.

Around the same time, the East India Company paid for printing Morrison's Chinese Dictionary. They spent £10,000 on the project. They even brought their own printer, Peter Perring Thoms, and a printing press. The Bible Society gave two grants of £500 each to help print the New Testament. One of the East India Company Directors also left Morrison $1000 to spread Christianity. Morrison used this money to print a small, pocket-sized edition of the New Testament. The earlier edition was too big. This was a problem because hostile authorities might seize and destroy the books. A pocket Testament could be carried easily. The small edition was printed. Many Chinese people left Guangzhou for the interior. They carried one or more copies of this valuable little book hidden in their clothes or belongings.

Mary Morrison was ordered to England. She sailed with her two children. For six years, her husband worked alone.

In 1817, Morrison joined Lord Amherst's trip to Beijing. His own knowledge of China greatly increased from this. The company sent him as an interpreter to the Emperor in Beijing. The journey took him through many cities and rural areas. It showed him new parts of Chinese life and character. The trip's main goal was not achieved. But for Morrison, the experience was very valuable. It helped his health and made him even more eager for missionary work. Across that huge country, among so many people, there was not one Protestant missionary station.

Another of Morrison's achievements was setting up a public clinic in Macau in 1820. There, local diseases could be treated more kindly and effectively. Morrison was deeply moved by the suffering of the Chinese poor. People often spent all their money on Traditional Chinese medicine that he thought was useless. Morrison found a smart and skilled Chinese doctor. He put him in charge of his clinic. This doctor had learned European treatment methods. He received great help from Dr. Livingstone, a friend of Morrison's. Dr. Livingstone was very interested in helping the suffering Chinese poor.

Morrison and Milne also started a school for Chinese and Malay children in 1818. The school was called Anglo-Chinese College. It was later named Ying Wa College. It moved to Hong Kong around 1843 after Hong Kong became a British territory. Today, this institution is a secondary school for boys in Hong Kong. Milne received support from the English Governor at Malacca. This college was the furthest east Protestant mission in Asia. Morrison called it the "Ultra-Ganges" mission.

Morrison and Milne translated the Old Testament together. Morrison knew the language much better. So, he could review Milne's work. But Milne also made great progress in learning Chinese. The printing press was always busy. They printed many different kinds of religious papers. Morrison wrote a small book called "A Tour round the World." Its goal was to teach Chinese readers about European customs and ideas. It also showed the good things that came from Christianity.

Even with all his work in China, Morrison started an even bigger plan. He wanted to build an "Anglo-Chinese College" in Malacca. Its goal was to connect the East and the West. It would help people from both cultures understand each other. This would prepare the way for Christian ideas to spread peacefully in China.

The idea was very popular. The London Missionary Society gave the land. The Governor of Malacca and many residents donated money. Morrison himself gave £1000 of his own money to start the college. The building was built and opened. Printing presses were set up, and students enrolled. Milne was the president. No student had to become a Christian or attend Christian worship. But they hoped that the strong Christian influence would lead many students to become Christian teachers. Morrison had strong Christian beliefs. But he would not force his beliefs on others. He believed that Christian truth would succeed on its own merits. It did not need to fear being compared with other religions. Eight or nine years after it started, a government report highly praised this institution. It noted its sound, quiet, and effective work.

A mission station was now set up under British protection. It was in the middle of islands with many Malay and Chinese people. More missionaries were sent from England. After some time in Malacca, they were sent to other places. These included Penang, Java, Singapore, and Amboyna. They went wherever they could find a place to stay and connect with people. Many new stations appeared in the Ultra-Ganges Mission. A magazine called The Gleaner was published. It helped the different stations stay in touch. It also shared information about progress in different areas. The printing presses produced many pamphlets, papers, catechisms, and Bible translations in Malay or Chinese. Schools were started to teach children. A big challenge was that few people could read. Missionaries had to do many different things. They preached to Malays, Chinese, and English people. They set up printing types. They taught in schools. They explored new areas and nearby islands. They also gathered their small groups of Christians at their own station. The reports did not change much year to year. The work was hard and seemed to produce few results. People listened, but often did not respond. There were few converts.

Mary Morrison returned to China only to die in 1821. Mrs. Milne had already passed away. Morrison was 39. In 1822, William Milne died. Morrison was left to realize that he was the only one of the first four Protestant missionaries to China still alive. He looked back at the mission's history by writing about these fifteen years. China was still very closed to European and Christian influence. But the amount of important literary work done was huge.

Scholarly Work

Robert Morrison's Dictionary of the Chinese Language was the first Chinese-English and English-Chinese dictionary. It was mostly based on the Kangxi Dictionary and another Chinese rhyming dictionary from that time. This meant his tone markings were from older Chinese, not how people spoke in his time. Because of his teachers, his spellings were based on Nanjing Mandarin, not the Beijing dialect.

Works

This is a list of important works by Robert Morrison:

- Alt URL

- The Morrison Collection Bibliography

See also

- Morrison Academy

- Yung Wing

- Raffles Institution, the oldest school in Singapore

- Ying Wa College, the world's first Anglo-Chinese school founded in 1818 by Morrison, now in Hong Kong

Images for kids

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |