Robert Stout facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Stout

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 13th Premier of New Zealand | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor | William Jervois |

| In office 16 August 1884 – 28 August 1884 |

|

| Preceded by | Harry Atkinson |

| Succeeded by | Harry Atkinson |

| In office 3 September 1884 – 8 October 1887 |

|

| Preceded by | Harry Atkinson |

| Succeeded by | Harry Atkinson |

| 4th Chief Justice of New Zealand | |

| In office 25 May 1899 – 31 January 1926 |

|

| Nominated by | Richard Seddon |

| Appointed by | Earl Ranfurly |

| Preceded by | James Prendergast |

| Succeeded by | Charles Skerrett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 September 1844 Lerwick, Shetland, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Died | 19 July 1930 (aged 85) Wellington, New Zealand |

| Political party | Liberal (1889–1896) |

| Spouse | Anna Paterson Logan (m. 1876) |

| Children | 6, including Duncan |

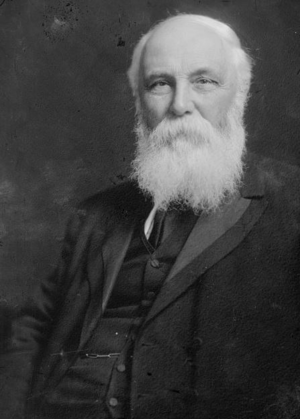

Sir Robert Stout (28 September 1844 – 19 July 1930) was an important New Zealand politician. He served as the country's Premier (like a Prime Minister) two times in the late 1800s. Later, he became the Chief Justice of New Zealand, which is the highest judge in the country. He was the only person ever to hold both these top jobs. Sir Robert Stout was known for supporting new ideas like women's suffrage, which meant giving women the right to vote. He strongly believed that good ideas and principles should always guide political decisions.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life and Education

Robert Stout was born in a town called Lerwick in the Shetland Islands of Scotland. He always felt a strong connection to his home islands. He got a good education and became a teacher. In 1860, he also qualified as a surveyor, someone who measures land. His family often talked about politics, which made him very interested in different political ideas from a young age.

In 1863, Stout moved to Dunedin, New Zealand. He quickly joined in political discussions, which he really enjoyed. He also became involved with groups that encouraged free thinking. After not finding work as a surveyor in the Otago gold-fields, Stout went back to teaching. He held several important teaching jobs at high schools.

Later, Stout left teaching to work in the legal profession. By 1867, he was working at a law firm. He officially became a lawyer on 4 July 1871. He was a very successful lawyer in court. He was also one of the first students at Otago University. There, he studied how economies work and ideas about right and wrong. He later became the university's first law lecturer.

Starting in Politics

Stout's political journey began when he was elected to the Otago Provincial Council. People were impressed by his energy and how well he spoke. However, some found him a bit difficult and thought he didn't respect different opinions enough.

In August 1875, Stout was elected to the New Zealand Parliament for the Caversham area. He tried to stop the government from getting rid of the provinces, but he wasn't successful. A few months later, in the 1875 election, he was elected again for the City of Dunedin.

On 13 March 1878, Stout became the Attorney-General (the government's chief legal advisor) in George Grey's government. He helped create many important laws in this role. On 25 July 1878, he also became the Minister of Lands and Immigration. Stout strongly believed the government should own land and then rent it to farmers. He worried that private land ownership would create a powerful class of landlords, like in Britain. He also supported taxing privately owned land, especially when its value increased.

On 25 June 1879, Stout left both the government and parliament. He said he needed to focus on his law practice because his business partner was ill. Being in politics was also very expensive for him and his family.

Around this time, Stout became friends with John Ballance, another politician who had left the government. Stout and Ballance shared many similar political views. While out of parliament, Stout started thinking about how political parties could work in New Zealand. He believed a united group of liberal politicians was needed. However, he eventually thought parliament was too divided for real political parties to form.

In the 1884 election, Stout returned to parliament. He tried to bring together different liberal politicians. He formed an alliance with Julius Vogel, who had been Premier before. This surprised many people because even though Vogel shared Stout's social views, they often disagreed on money matters.

Becoming Premier

In August 1884, just a month after returning to parliament, Stout led a vote that showed he had no confidence in the current Premier, Harry Atkinson. Stout then became Premier himself. Julius Vogel became the Treasurer, which gave him a lot of power in the new government. However, Stout's first government lasted less than two weeks! Atkinson managed to get his own vote of no confidence against Stout. But Atkinson couldn't form a government either, and he was removed by another vote. So, Stout and Vogel returned to power again.

Stout's second government lasted much longer. Its main achievements were making changes to the public service and creating a plan to build more high schools across the country. They also organized the building of the Midland railway line between Canterbury and the West Coast. However, the economy was struggling, and their efforts to improve it didn't work. In the 1887 election, Stout lost his own seat in parliament by a small number of votes. This ended his time as Premier. Harry Atkinson, his old rival, then formed a new government.

After this, Stout decided to leave parliamentary politics. He wanted to focus on other ways to promote liberal ideas. He was especially interested in solving problems between workers and businesses. He worked hard to bring together the growing labor movement and middle-class liberal thinkers.

The Liberal Party and Leadership Challenges

While Stout was out of politics, his friend, John Ballance, continued to fight in parliament. After the 1890 election, Ballance gained enough support to become Premier. Soon after, Ballance started the Liberal Party, which was New Zealand's first real political party. However, just a few years later, Ballance became very ill. He asked Stout to return to parliament and take over as leader. Stout agreed, and Ballance died shortly after.

Stout re-entered parliament after winning an election in Inangahua on 8 June 1893. Ballance's deputy, Richard Seddon, had already taken over leadership of the party. The plan was for the party members to vote later, but no vote ever happened. Stout, supported by those who thought Seddon was too traditional, tried to challenge this. But he was not successful. Many of Seddon's supporters believed that Ballance's and Stout's progressive ideas were too extreme for the public.

Stout stayed in the Liberal Party but often disagreed with Seddon's leadership. He claimed that Seddon was not following Ballance's original progressive ideas. Stout also said that Seddon was too controlling in his leadership style. Stout believed that Ballance's idea of a united progressive group had become just a way for the more traditional Seddon to gain power. Seddon argued that Stout was just upset about not becoming the leader himself.

Fighting for Women's Right to Vote

One of the last big campaigns Stout was part of was the effort to give women the right to vote. Stout had supported this cause for a long time. He had worked hard for his own bill in 1878 and Julius Vogel's bill in 1887, both of which failed. He also actively campaigned to increase property rights for women. He was especially concerned that married women should be able to own property separately from their husbands.

John Ballance had also supported women's right to vote. However, his attempts to pass a bill were blocked by the more traditional New Zealand Legislative Council (which was like an upper house of parliament, now gone). Richard Seddon was against women voting, and many thought the cause was lost. But a big effort by suffragists, led by Kate Sheppard, gained a lot of public support. Stout believed a bill could pass despite Seddon's objections. In 1893, a group of progressive politicians, including Stout, passed a women's suffrage bill through both houses of parliament. The upper house narrowly passed it, partly because some members who were against it changed their votes after Seddon tried to stop the bill.

In 1898, Stout retired from politics. He had represented several areas in parliament during his career.

Life After Politics

On 22 June 1899, Robert Stout was appointed Chief Justice of New Zealand. He held this very important position until 31 January 1926. As of 2011, Stout was the last Chief Justice of New Zealand to have also served in the New Zealand Parliament.

As Chief Justice, Stout was very interested in helping criminals improve their lives, which was called rehabilitation. This was different from the usual focus on just punishment at the time. He played a big part in organizing New Zealand's laws, which was finished in 1908. In 1921, he was made a Privy Councillor, a special advisor to the King or Queen. In the same year he retired, Stout was appointed to the New Zealand Legislative Council, which was his last political job.

Stout also played a very important role in developing New Zealand's university system. He became a member of the Senate of the University of New Zealand in 1885 and stayed there until 1930. From 1903 to 1923, he was the university's Chancellor, a top leader. He was also important at Otago University from 1891 to 1898, serving on its council. He was very involved in starting what is now Victoria University of Wellington. The strong connection between Victoria University and the Stout family is remembered by the university's Stout Research Centre and its Robert Stout Building.

In 1929, Stout became very ill and never recovered. He died on 19 July 1930 in Wellington.

Works

- The Rise and Progress of New Zealand historical sketch in Musings in Maoriland by Arthur T. Keirle 1890. Digitised by the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre

- Our Railway Gauge in The New Zealand Railways Magazine, Volume 3, Issue 2 (1 June 1928). Digitised by the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre

See also

- Robert Stout Law Library

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |