Robert Willis (engineer) facts for kids

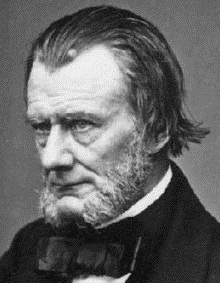

The Reverend Robert Willis (born February 27, 1800 – died February 28, 1875) was an important English scholar. He was the first professor at Cambridge University to be widely known as a mechanical engineer. He was also the first to seriously study vowel sounds in a scientific way. Today, he is best remembered for his many writings on architectural history. These include studies of medieval cathedrals and a four-volume book about the architecture of Cambridge University. A famous historian named Pevsner called him "the greatest English architectural historian of the 19th century."

Contents

About Robert Willis

His Early Life and Time in Cambridge

Robert Willis was born in London on February 27, 1800. His father, Dr. Robert Darling Willis, was a doctor to King George III. Robert Willis was tutored at home because he was often sick.

He was good at music and drawing. At 19, he even got a patent for a better pedal harp. In 1820, he saw a demonstration of the "Mechanical Turk". This was a machine that supposedly played chess by itself. The next year, Willis published a book explaining how a human player could be hidden inside the machine.

In 1821, he studied in King's Lynn. This town had many old churches and guildhalls. Here, Willis became very interested in architecture. He made his first known architectural drawings. Experts noted his skill in showing how buildings were put together, even without formal training. In 1822, he started at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He earned his degree in 1826. He became a Fellow of the College and was ordained as a deacon and priest. He married Mary Anne Humfrey in 1832. They lived in Cambridge for the rest of their lives.

The 1830s were an exciting time for science in Cambridge. A group of scholars, called the "Cambridge Network," were making big discoveries. Two important people were Charles Babbage and William Whewell. Babbage was building his difference engine, an early mechanical computer. Willis drew detailed pictures of its parts. Whewell shared Willis's interests in science, architecture, and math. They remained friends and colleagues for life.

Studying Vowel Sounds (Phonetics)

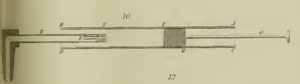

In 1828 and 1829, Willis presented papers about how vowel sounds are made. These were published in 1830. Because of this work, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1830. He used a special machine with a reed and a tube that could change length. Different vowel sounds were made by changing the tube's length.

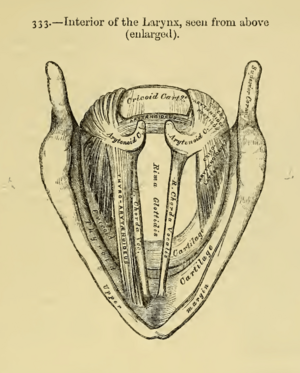

His idea that vowel sounds depended on one main frequency was too simple. However, his work was the first careful study in this area. It helped future research a lot. In 1833, he published a paper on the larynx, which is part of your throat that helps you speak. He used models and studied the larynx to understand how it works. Willis correctly identified the muscles that stretch and relax the vocal ligaments (vocal cords). He also found the muscles that open and close the airways. This allows either sound production or normal breathing. Years later, his diagram of the larynx was used in the famous book Gray's Anatomy.

His Work in Engineering

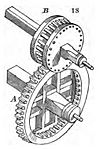

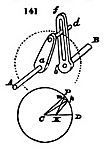

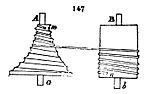

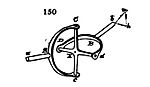

From 1837 to 1875, Willis was a professor of Natural Philosophy at Cambridge. From 1853, he also taught applied mechanics at a government school of mines. In 1837, he wrote about the "teeth of wheels" (gears). The next year, he published more details and introduced the Odontagraph. This tool helped workers draw the correct shape for gear teeth on wheels of different sizes. It was used for many years. He also published Principles of Mechanism in 1841.

Principles of Mechanism was Willis's most important engineering book. It used math to analyze how parts of machines move together. He looked at machines based on how their parts touched: rolling, sliding, wrapping, linking, and reduplicating. He also looked at whether the movement between parts was fixed or could change. He showed that a crab's claw worked like Hooke's universal joint. Willis's way of classifying machines was very influential. Many other writers used his system.

- Examples of how Willis classified mechanisms (from his 1841 book)

Architecture and Cathedral Histories

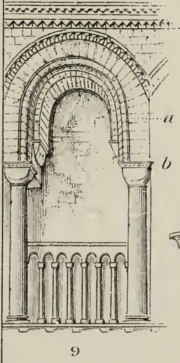

Willis's first book on architecture was Remarks on the architecture of the middle ages, especially of Italy (1835). He wrote it after his honeymoon trip in 1832-33. He looked at the Gothic style in general, not just Italian buildings. He saw a difference between a building's real structure and how it appeared. He called these the mechanical and decorative parts. For example, an arch looks like it's supported by the column it springs from. But the actual forces might be at a different point. For a building to look good, the apparent (decorative) structure must look stable and harmonious.

Willis also studied the history of individual buildings. These included Hereford Cathedral (1842), Canterbury Cathedral (1845), and Winchester Cathedral (1846). Many of his cathedral studies started as lectures. He often gave guided tours of the buildings. Most of these were later published.

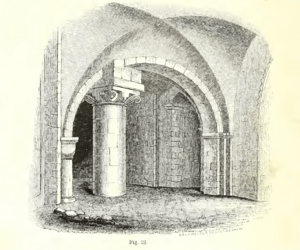

Willis used both old documents and detailed examinations of the buildings. For his book on Canterbury Cathedral, he said he would "collect all the written evidence, and then by a close comparison of it with the building itself, to make the best identification." He was known for being able to tell different building periods apart. He looked at styles and breaks in the structure. His 1845 book on Canterbury was the first English book called an "architectural history." Canterbury Cathedral has many old records. Willis used these records, including accounts from two monks, Edmer and Gervase. He translated Gervase's account, which described a fire in 1174 and the rebuilding. The fire destroyed the Norman choir but not the crypt. Willis showed how new columns were added to the crypt to support the new upper structure. These columns did not match the old layout.

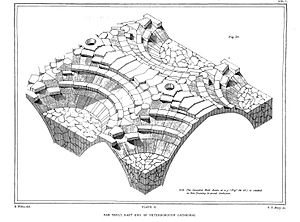

Willis also gave lectures on Gloucester and Peterborough Cathedrals. For Gloucester, he started excavations. He looked for possible Saxon work in the crypt. He found that Gloucester showed the earliest use of the Perpendicular Gothic style (around 1337). Willis had also identified the vaults of the Gloucester cloister as the earliest example of fan vaulting in England. For Peterborough, Willis described several vaults. He included drawings of the fan vaulting in his book On the Construction of the Vaults of the Middle Ages.

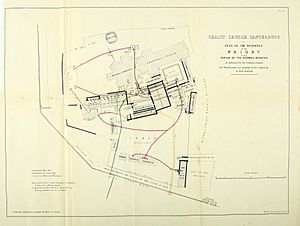

His last historical study published during his life was about the monastic buildings at Canterbury. It came out in 1868. Christ Church Canterbury was the largest monastery in England. It had about 150 monks. Monasteries were different from churches. Monasteries were shut down in the 16th century, and many parts were destroyed. What was left was changed for new uses. So, identifying the different parts of the monastery was a big job. Canterbury had many documents, including a famous "waterworks plan." This plan showed the pipes and cisterns installed in the 12th century. It also showed the buildings that existed at the time. Willis reproduced this plan and made his own version. His version lined up the plan with known existing structures. He also paid attention to daily life. For example, he discussed the "necessarium" (latrine). He mentioned instructions for a watchman to check the seats at night in case monks fell asleep. Willis thought this might be why it was also called the "Third Dormitory."

To help with his descriptive work, he invented the Cymagraph in 1842. This tool copied the shapes of architectural moldings.

Societies and Special Projects

In 1839, the Cambridge Camden Society was formed by students to study Gothic Architecture. Willis became a Vice-President. Willis agreed that medieval Gothic was good for new churches. But he disagreed with the society's focus on old church rituals. He resigned in 1841. Also in 1841, Willis designed his only complete building. It was a cemetery chapel in Wisbech. This was an early example of historically accurate Gothic style in England.

Willis was an early member of the British Archaeological Association. He gave his paper on Canterbury Cathedral at their first meeting in 1844. Later, he joined the Royal Archaeological Institute. In 1849, he was part of a Royal Commission. This group studied how iron was used in railway structures. Willis did experiments to see how moving loads affected iron. He was also a judge at the Great Exhibition of 1851. In 1855, he was a vice-president at the Paris Exposition. In 1862, he received the Royal Gold Medal for architecture.

His Later Years and Books Published After His Death

In 1870, his wife Mary Ann died. After finishing the second edition of Principles of Mechanism that year, Willis stopped writing. In 1872, he sold his large library of books. He died from bronchitis in 1875 in Cambridge. His papers are kept at the Cambridge University Library. He left his unfinished book, Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, to his nephew John Willis Clark. His nephew finished it, and it was published in 1886.

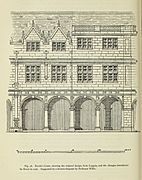

The Cambridge History was Willis's most important work. It has four volumes. It describes each college and the main University buildings in detail. He used many old documents, like University records and account books. From these, he showed that early colleges did not have chapels at first. Students used the local church instead. This went against some beliefs at the time. He also showed how Oxford and Cambridge colleges were similar to monasteries and private houses. The Cambridge History is still used today.

His Lasting Impact

Willis's ideas about how vowel sounds are made were very important. He thought vowel production was like playing an organ. The lungs were like bellows, vocal folds like reeds, and the mouth cavity like an organ pipe. Different vowels came from mouth cavities of different lengths. His 1830 paper on vowel sounds is often mentioned for this idea.

Today, Willis is best known for his work on architecture. Historians like Pevsner and Bony have said that his work is still very valuable. Pevsner noted that Willis's results "have remained valid to this day." Bony called his 1845 book on Canterbury Cathedral "the fundamental monograph." Another expert, Huerta, said Willis's work on vaults is "still today the best exposition of the topic."

Not to Be Confused With Another Robert Willis

Sometimes, Robert Willis's work on sound is mistakenly given to another person named Robert Willis (1799–1878). This happens in some books. Other times, the dates for the architect Robert Willis are incorrectly given as 1799–1878.

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |