Rodrigues night heron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rodrigues night heron |

|

|---|---|

|

|

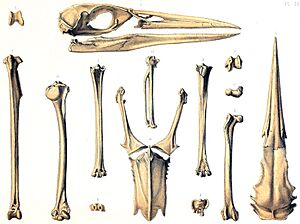

| Subfossil skull, limb bones, and sternum, 1873 | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Nycticorax |

| Species: |

†N. megacephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Nycticorax megacephalus (Milne-Edwards, 1873)

|

|

|

|

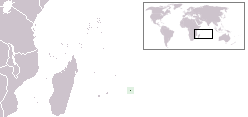

| Location of Rodrigues | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ardea megacephala Milne-Edwards, 1873 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Rodrigues night heron (Nycticorax megacephalus) was a type of heron that lived only on the island of Rodrigues. This island is in the Indian Ocean. Sadly, this bird is now extinct, meaning it no longer exists.

People first wrote about these birds as "bitterns" in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Later, in the 1800s, scientists found subfossil bones of the bird. These bones showed it was a heron, not a bittern. It was first named Ardea megacephala in 1873. Then, in 1879, it was moved to the night heron group, Nycticorax. Its scientific name, megacephala, means "great-headed" in Greek. Two other related herons from nearby islands, the Mauritius night heron and the Réunion night heron, are also extinct.

The Rodrigues night heron was a strong, sturdy bird. It had a large, thick, straight beak and short, powerful legs. It was about 60 centimeters (24 inches) long. We don't know exactly what it looked like when it was alive. Males were bigger than females. Not much is known about how it behaved. But old writings say it ate lizards, like the Rodrigues day gecko. It was good at running and could fly, but it rarely did. Scientists have studied its bones and agree it was adapted for life on the ground. The bird was gone by 1763. It likely became extinct because of humans, especially due to introduced predators like cats.

Contents

Discovering the Rodrigues Night Heron

The French traveler Francois Leguat wrote about "bitterns" in his 1708 book. He lived on Rodrigues island from 1691 to 1693. Leguat's notes are some of the first detailed writings about wild animals.

In 1873, French scientist Alphonse Milne-Edwards studied bird bones from Rodrigues. These bones were found in a cave in 1865. Milne-Edwards thought these bones belonged to the "bitterns" Leguat wrote about. But he realized they were from a type of heron. This heron had a large head and short legs. This made it seem like a bittern.

Milne-Edwards named the new bird Ardea megacephala. The name megacephala means "great-headed" in Greek. This refers to the bird's large head and jaws. The bones he studied included the skull, leg bones, and breastbone.

In 1875, Alfred Newton found another old writing from 1725–26 by Julien Tafforet. This writing also mentioned "bitterns." Newton believed this confirmed Milne-Edwards' findings. More fossils were found in 1874. German scientist Albert Günther and E. Newton described them in 1879. They found that the bones were very similar to those of the night heron group, Nycticorax. So, they changed the bird's name to Nycticorax megacephalus.

Over the years, scientists debated where this bird belonged. Some thought it was very different from other herons. In 1937, Masauji Hachisuka even put it in a new group called Megaphoyx. He also called it the "Rodriguez flightless heron." This was because he thought it could not fly. But most scientists today keep it in the Nycticorax group. They also believe it could still fly, even if not very well.

Scientists like Julian P. Hume explain that night herons often move to islands. On islands without many land mammals, they become more adapted to living on the ground. This means their legs get stronger and their wings get shorter. This makes them fly less. The Rodrigues and Mauritius night herons seem to be closely related.

Appearance of the Rodrigues Night Heron

The Rodrigues night heron was a sturdy bird. It had a large, thick, straight beak. Its legs were short and strong, even stronger than those of the Mauritius night heron.

Males and females looked different, which is called sexual dimorphism. Males were larger than females. For example, the male's lower leg bone (tibiotarsus) was about 17.5% longer than the female's.

This heron was estimated to be about 60 centimeters (24 inches) long. Its skull was about 15.4 cm (6.1 in) long. The upper part of its beak was about 9.4 cm (3.7 in) long.

The wing bones of the Rodrigues night heron were quite small. But its leg bones, especially the thigh bones, were longer than those of living herons. This shows it was more adapted to walking and running.

We are not sure what colors the Rodrigues night heron was. Leguat called them "bitterns," which are often brownish. Tafforet called them "egrets," which are white. Some scientists think the Mascarene herons kept their juvenile (young bird) plumage as adults. This means they might have looked like young night herons, which are often grey with white-tipped feathers.

Life and Habits of the Rodrigues Night Heron

We know little about how the Rodrigues night heron lived. Most of what we know comes from two old descriptions.

Leguat wrote in 1708:

We had Bitterns as big and as fat as capons. They are tamer and more easily caught than the 'gelinotes' [Rodrigues rails]... The lizards often serve as prey for the birds, especially for the Bitterns. When we shook them down from the branches with a pole, these birds ran up and gobbled them down in front of us, in spite of all we could do to prevent them; and even if we only pretended to do so they came in the same manner and always followed us about.

The "lizards" were likely geckos like the Rodrigues day gecko. These geckos could grow up to 23 cm (9.1 in) long. Leguat and his friends liked these tame lizards. They even let them eat from their tables. The herons were quite bold and would try to eat the lizards right in front of them. This shows the birds were very tame and not afraid of humans. This is common for many island birds.

Scientists think the Rodrigues night heron also ate snails. It probably hunted on land, not in wetlands or by the shore. It might have also eaten eggs and young of giant tortoises. The large jaws suggest it ate bigger prey. Males and females might have eaten different foods. This could be because resources were limited on the island.

The heron likely lived and hunted in open forests with palm trees. These areas would have had geckos and other small creatures. It might have also scavenged for food from seabird nests or giant tortoise breeding areas. It probably nested on the ground or in low bushes.

Many other animals unique to Rodrigues also became extinct after humans arrived. The island's natural environment is now very different. Before humans, forests covered the whole island. The Rodrigues night heron lived with other now-extinct birds. These included the Rodrigues solitaire, Rodrigues parrot, and Rodrigues rail. Extinct reptiles included two types of Rodrigues giant tortoise.

Flight and Running Abilities

In 1873, Milne-Edwards thought the Rodrigues night heron's breastbone was weak. This meant its wings were not strong enough for powerful flight. He also noted its legs were short but strong. This suggested the bird had a bulky body.

Tafforet's 1725–26 account also said the bird flew very little. He wrote:

There are not a few Bitterns which are birds which only fly a very little, and run uncommonly well when they are chased. They are of the size of an egret and something like them.

Scientists Günther and Newton agreed in 1879. They found the wing bones were smaller compared to other night herons. But the leg bones were very well-developed and thicker. This showed the bird was much better at running. They believed it chased fast land animals, like lizards, instead of water prey. They concluded it could still fly, but its strong legs made up for weaker wings.

Some scientists, like Hachisuka, thought the bird was completely flightless. But others, like Storrs L. Olson, disagreed. They pointed out that the bird's breastbone still had a good keel (a bone structure for flight muscles). This meant it could still fly, even if not strongly.

In 1987, Graham S. Cowles confirmed that the Rodrigues night heron's leg bones were stronger and more robust. This showed its legs became stronger as it needed to fly less. This is a common change in birds living on islands.

In 2007, scientists called the Rodrigues and Mauritius night herons "behaviourally flightless." This means they rarely flew, but could if they had to. Julian P. Hume noted in 2023 that the Rodrigues night heron had special leg features. These gave it strong control over its toes for walking and running. He concluded it was on its way to becoming flightless. Its strong adaptations for living on land were due to the lack of wetlands on Rodrigues.

Why the Rodrigues Night Heron Disappeared

Night herons on large continents are usually safe. But those on small islands are very vulnerable to human actions. Six out of nine known island species are now extinct.

[[multiple image |direction = horizontal |align = right |total_width = 400 |image1 = Rodrigues.jpg |alt1 = Map of Rodrigues, decorated with solitaires |image2 = Leguat Settlement.jpg |alt2 = Map of human settlement on Rodrigues |footer = Leguat's 1708 maps of Rodrigues and his settlement. ]]

Hume noted in 2023 that these herons lived with introduced rats for centuries. They were common until the late 1600s and early 1700s. These large birds could likely defend their young from rats. Cats were brought to the island to control rats. But the cats became wild and hunted the herons, especially the young ones.

In 1763, French astronomer Alexandre Guy Pingré visited Rodrigues. He noticed that the Rodrigues night heron and other birds were gone. He wrote that they might have "retreated from their homes" or, more likely, "the races no longer survive, since the island has been populated with cats."

No one mentioned the Rodrigues night heron after Pingré's visit. It likely became extinct around this time. Scientists believe its inability to fly well made it an easy target. The extinction was caused by severe deforestation (cutting down forests) and introduced predators like cats. Some scientists argue that cats were the main reason, as there wasn't much deforestation at the time.

Hume stated in 2023 that the Rodrigues night heron was numerous during Leguat's and Tafforet's visits. But when a small French group settled on the island in 1736, it marked the beginning of the end. These hunters probably killed some birds. But the introduction of cats in 1750 was likely the main cause of their extinction. This happened quickly, probably by Pingré's visit in 1761.

Night herons are good at reaching new islands. But they become vulnerable when they change from living in water to living on land. This makes them more affected by hunting, habitat loss, and new predators. The fossil record helps us understand these extinctions. Many more extinct island herons may still be discovered.