Rosika Schwimmer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rosika Schwimmer

|

|

|---|---|

| Schwimmer Rózsa | |

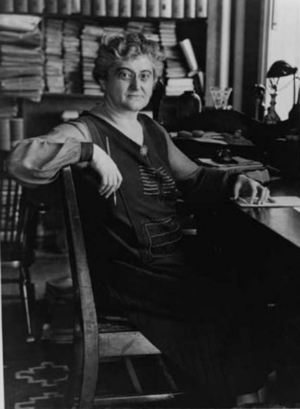

Rosika Schwimmer, by fellow Hungarian suffragist, Olga Máté, around 1914

|

|

| Born | 11 September 1877 |

| Died | 3 August 1948 (aged 70) New York City, U.S.

|

| Nationality |

|

| Other names | Rózsa Bédi-Schwimmer, Rózsa Bédy-Schwimmer, Róza Schwimmer |

| Occupation | Journalist, lecturer, activist |

| Years active | 1895–1948 |

| Known for |

|

| Relatives | Leopold Katscher (maternal uncle) |

Rosika Schwimmer (Hungarian: Schwimmer Rózsa; born September 11, 1877 – died August 3, 1948) was an important activist from Hungary. She believed strongly in peace (pacifist), equal rights for women (feminist), and the idea of countries working together globally (world federalist). She also fought for women's right to vote (women's suffragist).

Rosika Schwimmer helped start the Campaign for World Government. Her big dream was for world peace, which led to the creation of the World Federalist Movement. This was the first organization of its kind in the 1900s. Sixty years after she first thought of it, the movement she helped create played a big part in forming the International Criminal Court. This court is the first permanent international court that can charge people with war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Rosika was born into a Jewish family in Budapest in 1877. She finished public school in 1891 and was very good at languages, speaking or reading eight of them. Early in her career, she found it hard to get a job that paid enough to live on. This experience made her care deeply about women's job issues. She started collecting information about women workers and soon became involved in the women's right to vote movement by 1904. She helped create the first national group for women's labor in Hungary and the Hungarian Feminist Association. She also helped organize a big international meeting for women's suffrage in Budapest in 1913.

In 1914, Rosika became a press secretary for an international women's suffrage group in London. When World War I started, she was seen as an "enemy alien" because of her Hungarian background. She left Europe for the United States, where she spoke about women's right to vote and peace. She was one of the people who started the Woman's Peace Party and the organization that later became the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

In 1915, after attending a women's congress in The Hague, she worked with other women to convince leaders in Europe to support a group that would peacefully solve world problems. She also helped convince Henry Ford to fund the "Peace Ship." From 1916 to 1918, Rosika lived in Europe, working on different plans to end the war. When Hungary became a republic in 1918, she was appointed as one of the world's first female ambassadors, representing Hungary in Switzerland. When the government was overthrown, she fled to the United States and gave up her Hungarian citizenship.

Rosika tried to become a U.S. citizen, but her application was turned down because she was a pacifist. Her case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1929, which upheld the decision against her. For the rest of her life, she remained without a country (stateless). She couldn't work much due to health problems and false accusations against her, so friends supported her.

In 1935, Rosika and Mary Ritter Beard created the World Center for Women's Archives. This was a place to collect and share information about women's history and their achievements. In 1937, she was one of the first to suggest the idea of a world government. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1948 but passed away before the decision was made. In 1952, U.S. laws about becoming a citizen were changed to allow for people who refused to fight in wars for moral or religious reasons (conscientious objection).

Contents

Rosika Schwimmer's Early Life

Rózsa Schwimmer was born in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, on September 11, 1877. Her parents were Bertha and Max Bernat Schwimmer. She was the oldest of three children and grew up in a well-off Jewish family in Temesvár, which is now Timișoara, Romania. Her father was a merchant who traded farm products and also ran an experimental farm. Her uncle, Leopold Katscher, was a famous writer and peace activist who greatly influenced Rosika.

She went to primary school in Budapest and later to a convent school in Transylvania. After graduating from public school in 1891, she studied music and languages. Even though she only went to school for eight years, she could speak English, French, German, and Hungarian. She could also read Dutch, Italian, Norwegian, and Swedish. In 1893 and 1894, she took evening classes at a business school. Her family had to return to Budapest when her father's business failed.

Rosika Schwimmer's Career and Activism

Early Work and Becoming an Activist

Rosika Schwimmer first worked as a governess, then had several short jobs. In 1895, she became a bookkeeper and a clerk who wrote letters. In 1897, she started working for the National Association of Women Office Workers and became its president by 1901. She had experienced how hard it was for women to find jobs that paid enough, especially when society didn't encourage women to be financially independent. This made her want to help working women.

Since national trade unions weren't interested in helping women workers, she started collecting information and statistics herself. She wrote to government departments and looked at old journals to understand women's education and work conditions. To compare Hungary's situation with other countries, Rosika wrote to international women's rights groups to gather statistics.

Through her letters, Rosika connected with important international women's movement leaders. They encouraged her to start a women's organization that would bring together different groups working on women's issues. After losing her job, Rosika became a journalist in late 1901. She wrote for various newspapers and international feminist magazines. She also translated books, like "Women and Economics" by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, into Hungarian.

In 1903, she co-founded the Hungarian Women Workers Association with Mariska Gárdos. This was the first national organization for women laborers. The next year, she attended the first conference of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. She spoke about the working conditions of industrial workers in Hungary. There, she met many leading feminists. Carrie Chapman Catt, an American suffragist, was impressed by Rosika and asked her to help with the women's right to vote efforts. They became close friends, with Catt guiding Rosika.

When she returned home, Rosika co-founded the Hungarian Feminist Association with Vilma Glücklich. Other important feminists joined them. This group worked for gender equality in all parts of women's lives. This included education, jobs, laws for married women, the right to vote, and inheritance rights. They also worked to stop child labor. In 1907, to fight against negative news reports, the Feminist Association started its own journal, "Women and Society," with Rosika as the main editor. It published articles on careers, child care, housework, and legal issues.

Rosika became well-known that year for arguing with a law professor and politician named Károly Kmety. He wanted to make it harder for women to get into higher education. Kmety called educated women "female monsters" who wanted to destroy families. Rosika showed that Kmety's own wife had graduated from a teaching school, winning the argument. Even so, the Feminist Association continued to face criticism.

In 1913, Rosika helped the Feminist Association organize the Seventh Conference of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Budapest. This big event, from June 15 to 21, had support from the government and the city. It was the first large international meeting of its kind in Austria-Hungary, bringing together about 3,000 delegates from around the world. Rosika arranged for university students to translate and gave an update on how women's right to vote was progressing in Hungary. Trips were also organized so feminists could see more of the country. The way the feminists behaved at the conference changed old ideas about women's rights activists. After the conference, Rosika changed the name of the Feminist Association's journal to "The Woman." In August, she attended a peace congress in The Hague, which made her even more interested in peace.

By this time, Rosika had traveled widely in Europe, giving lectures. She was outgoing and an experienced journalist, knowing how to connect with her audience. She was known for her humor and clever jokes. She could convince men to support women's rights and made women laugh at men with sharp, funny remarks. She had a strong, energetic personality, which some called stubborn. She often went beyond what women were expected to do at the time. She was a strong believer in peace, a humanist (focused on human values), and an atheist (did not believe in God). Because she was Jewish and from another country, she often faced attacks based on her background and nationality. She smoked and drank wine, which was unusual then, and wore loose, comfortable dresses with her special glasses. She described herself as a "very, very radical feminist" and people often either loved or hated her.

Working for Peace Worldwide

Rosika's international connections led her to become the press secretary of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, so she moved to London. She also wrote for various European newspapers. When World War I started, she couldn't go home and began to push for the war to end. She left her job with the Suffrage Alliance, worried that her nationality would cause problems for the women's movement and her peace efforts. In 1914, she was labeled an "enemy alien" and left Britain to travel the United States, urging for an end to the war. Rosika spoke in 22 different states, telling women to push for diplomatic talks to solve the European conflict. She met with President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, but she couldn't get them to organize a neutral conference to bring both sides of the war together.

Rosika helped form the Woman's Peace Party in 1915 and became its secretary. Because of the war, the International Woman Suffrage Alliance's conference was postponed. Other suffragists suggested holding a conference to talk about international peace, and the Netherlands, as a neutral country, offered to host. Rosika helped organize the International Congress of Women in The Hague, which started on April 28. There, Rosika and Julia Grace Wales suggested creating a "continuous conference of neutrals" between governments to solve conflicts and bring peace. During the conference, the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace was formed, which later became the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Rosika was chosen as one of its board members.

After the conference ended on May 3, 1915, Rosika, Jane Addams, and other women met with European leaders over several months. The leaders, though hesitant, agreed to participate in a neutral assembly if other nations agreed and if U.S. President Woodrow Wilson started it. But Wilson refused during the war. By the time Rosika returned from Europe, many feminists in the U.S. believed that being a pacifist would hurt the cause for women's right to vote. Rosika disagreed. She felt that the fight for women's rights shouldn't only focus on voting. She strongly believed bigger changes were needed and that women's voices were vital to stop violence. She also felt that other leaders weren't working hard enough to get wide support for peace work. Determined to continue pushing for a peace conference, she decided that if politicians and feminists wouldn't act, individuals would have to work to end the war.

Henry Ford, the car maker, had promised $10 million for peace efforts to end the war. Teachers and poets helped arrange a meeting between Ford and Rosika. In early December, she sailed on a "Peace Ship" to Stockholm, funded by Ford, with him and other pacifists. The ship arrived in Norway on December 18. However, without a clear plan, the pacifists on board argued for power. Rosika was disliked because she had been trusted with international letters from leaders. Facing ridicule from the press and suspicion because of her Hungarian background, Ford returned to the U.S., leaving the peace mission. Rosika was disappointed but kept trying for several months. However, exhaustion and a heart condition led her to resign from the mission in March 1916. She was also hurt by the lack of support from other peace leaders and resigned from the committee. She couldn't return to the U.S. until August and stayed only about a month before going back to Sweden due to illness.

The "Peace Ship" event marked the start of false accusations against Rosika. Even though Henry Ford's anti-Jewish beliefs came before he met Rosika, the American press blamed her for his prejudices. She was also accused of tricking Ford out of money, being a German spy, and a communist agent. She stayed in Europe until the end of the war, returning to Hungary in 1918. When Hungary gained independence, Mihály Károlyi became the new prime minister. He appointed Rosika as the ambassador to Switzerland, making her one of the world's first female ambassadors. Károlyi also proposed a law giving literate women over 24 the right to vote, which passed later that year. In February 1919, Rosika organized a peace conference in Switzerland. However, she was called back from her job just days before a communist takeover in March. Barred from leaving Hungary, Rosika couldn't attend another peace conference in May.

The communist government was soon overthrown, and a period of violence followed. In 1920, Rosika fled to Vienna, where she lived as a refugee, supported by her friend Lola Maverick Lloyd, until she got permission to move to the United States in 1921.

Without a Country

Rosika gave up her Hungarian citizenship and arrived in the United States on August 26, 1921. She planned to continue her journalism and lecturing, but she found she was blacklisted. In 1919, New York State had investigated radical people and groups that might threaten national security. This included educators, journalists, and reform groups. Feminists and pacifists were seen as dangerous, especially the women who started the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Rosika was listed as a dangerous person in the report. Military officials and right-wing women's groups spread fear, making people suspicious of pacifists and suffragists.

Rosika was accused of preventing the U.S. from preparing for the war sooner. She was called a spy, and her peace efforts were twisted into plots to help the Germans. Other false claims said she was a diplomat in the brief communist government and part of an international Jewish conspiracy. To protect the women's right to vote campaign, other leaders distanced themselves from Rosika, which hurt her deeply. The Jewish community, which had welcomed her before the war, largely blamed Rosika for Ford's anti-Jewish campaign, even though Ford never said she played such a role.

In 1924, Rosika applied to become a U.S. citizen. She left questions about military service blank, thinking they didn't apply to women. She was later asked if she would bear arms (fight in a war). Rosika, believing in honesty and that no woman was forced to fight, answered that she would not personally take up arms. Two years later, she explained that defending the country didn't always mean physical fighting but could be a verbal or written defense of principles. She was also questioned about her atheism, her views on nationalism, and her commitment to peace. Rosika said faith was a personal choice and that she had given up her Hungarian citizenship to become a U.S. citizen. She repeated that she would not give up her pacifism.

Her application was denied only because she refused to fight in defense of the country. She appealed the decision. Being famous and facing negative publicity made it hard for her to earn a living or support her mother and sister, who lived with her. She spent most of her remaining life fighting false accusations. After a newspaper editor accused her of being a German spy and a communist agent, she sued and won $17,000 in damages in July 1928. The next day, her citizenship appeal was overturned, with the court saying that "women are considered incapable of bearing arms" and thus couldn't be forced to do so.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court was asked to review this decision. Believing Rosika's influence as a writer and speaker could make others refuse military service, they reviewed the case. In a 6-to-3 decision on May 27, 1929, the Supreme Court ruled that pacifists should not be allowed to become citizens. In a differing opinion, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. argued that free thought was a core part of the Constitution. He also pointed out that as a woman over 50, even if she wanted to fight, she wouldn't be allowed to.

Later Life and Legacy

After being denied citizenship, Rosika Schwimmer became stateless and remained so for the rest of her life. She suggested that the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom hold a conference about people without a nationality. The event took place in Geneva in 1930, and she wrote a plan for world citizens to be recognized internationally. Because of poor health, including complications from diabetes, and being unable to work, loyal friends supported her. In the early 1930s, she moved to New York City, living with her sister and secretary. In 1935, she started the World Center for Women's Archives with Mary Ritter Beard. The goal of this archive was to collect and share information about the achievements of important women. Rosika received an honorary World Peace Prize in 1937, which gave her $7,000.

Also in 1937, Rosika and Lola Maverick Lloyd formed the Campaign for World Government. This was the first organization of its kind in the 20th century to promote the idea of a world government. The group aimed to create a world government with a constitution, elected representatives, a legal system to solve conflicts between nations, and an International Criminal Court to deal with human rights issues. Rosika was one of the first people to support the creation of the International Court of Justice. She believed it would ensure equal participation and protection for all people, no matter their background or gender. Between 1938 and 1945, Rosika worked to help European friends escape from Nazi Germany. In 1946, the Supreme Court's decision in her citizenship case was overturned, meaning the earlier ruling was incorrect. In 1948, she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. However, no prize was given that year.

Rosika Schwimmer passed away from pneumonia on August 3, 1948, in New York City. She was buried the next day. She is remembered as one of the main spokespersons for Hungarian women before World War I and as a co-founder of the Hungarian women's right to vote movement.

Rosika's story shows the big changes that happened in the United States between the two World Wars. Even though she never became an American citizen, her life reflected shifts in American society and values. When she first arrived in the U.S., there was hope that World War I would end quickly. But when she returned in 1921, her belief in peace was seen as disloyalty.

Although the Peace Ship mission was largely seen as a failure, it changed how war news was reported in Europe, which had been heavily censored. The conference started in Stockholm in February 1916 helped discuss the war and how to end it. It also helped neutral countries avoid pressure to join the war. Her citizenship case led to a long campaign to change naturalization laws. These laws were finally changed in 1952 to allow people who refused to fight for moral or religious reasons to become citizens, as long as they agreed to serve in a non-fighting role.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rosika Schwimmer para niños

In Spanish: Rosika Schwimmer para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |