Rudolf Slánský facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

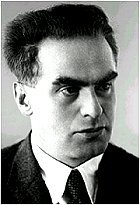

Rudolf Slánský

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 31 July 1901 Nezvěstice, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | 3 December 1952 (aged 51) |

| Nationality | Czechoslovakia |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Known for | General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia |

Rudolf Slánský (born July 31, 1901 – died December 3, 1952) was a very important Communist politician in Czechoslovakia. After World War II, he became the General Secretary of the Communist Party. This made him one of the main people who helped set up and run the Communist government in Czechoslovakia.

Later, there was a disagreement between Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Because of this, Stalin started to remove leaders from Communist parties in countries near the Soviet Union. He wanted to make sure no other countries would break away like Yugoslavia did. In Czechoslovakia, Slánský was one of 14 leaders arrested in 1951. They were forced to say they had committed crimes and were put on a public trial in November 1952. They were accused of being traitors. After eight days, 11 of the 14 were found guilty and sentenced to death. Slánský was executed five days later.

Contents

Early Life and Political Start

Rudolf Slánský was born in Nezvěstice, a town that is now in the Plzeň-City District. His family was Jewish and held traditional views. He went to high school in Plzeň at a business academy.

After World War I ended, he moved to Prague, the capital city. There, he found many people who were interested in left-wing ideas, especially at places like the Marxist Club. In 1921, Slánský joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. This party had just separated from the Social Democratic Party. He quickly moved up in the party and became a close helper to its leader, Klement Gottwald. At a big party meeting in 1929, Slánský became a member of the party's main groups, the Presidium and the Politburo. At the same time, Gottwald became the General Secretary.

From 1929 to 1935, Slánský had to live in secret because the Communist Party was not allowed to operate openly. In 1935, when the party was finally allowed to take part in politics, both he and Gottwald were elected to the National Assembly, which is like a parliament. However, their progress stopped when Czechoslovakia was divided up at the Munich Conference in 1938. After Nazi Germany took over a part of Czechoslovakia called the Sudetenland in October 1938, Slánský and many other Czechoslovak Communist leaders went to live in the Soviet Union.

In Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union, Slánský worked on radio broadcasts that were sent to Czechoslovakia. He was there during the Battle of Moscow in the winter of 1941-1942, when the city was defended against the Germans. His time in Moscow helped him learn about the Soviet Communists and their strict ways of keeping party members in line.

While living in the Soviet Union, Slánský also helped organize Czechoslovak army units. He returned with these units to Czechoslovakia in 1944 to take part in the Slovak National Uprising, which was a fight against the Germans.

Becoming Powerful After the War

In 1945, after World War II, Slánský and other Czechoslovak leaders came back from living in other countries like London and Moscow. They held meetings to set up a new government called the National Front, led by Edvard Beneš. At a major meeting of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party in March 1946, Slánský was chosen as the General Secretary of the party. He was the second most powerful person in the party, right after the party chairman Gottwald. Gottwald became the leader of a coalition government after elections that year.

In 1948, the Communist Party took control of the country in what is known as the February coup. After this, Slánský became the second most powerful person in Czechoslovakia, after Gottwald. At this time, some people started to blame Slánský for problems with the economy and industry, which made him less popular. However, he was also given the Order of Socialism, a very high award, on July 30, 1951. There were even plans to publish a book of his speeches supporting socialism, called Towards the Victory of Socialism.

The Trial

In 1951, after Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia broke away from Joseph Stalin, Stalin decided to "clean out" the Communist parties in the countries that were allied with the Soviet Union. He wanted to prevent any more revolts against his rule. Most historians believe that President Gottwald of Czechoslovakia, fearing he might be arrested, decided to sacrifice his friend, Rudolf Slánský, to save himself. On November 24, 1951, Slánský was arrested and put in prison. For the next year, he was forced to confess to "crimes" he did not commit. Other people, like Bedřich Geminder and Jarmila Taussigová, were also arrested on the same day. The Soviet Union's official message at the time was against Zionism, and Stalin wanted to keep strong control over the countries in Eastern Europe.

The Communist Party said that Slánský was spying as part of a plan by Western countries to harm socialism. They also claimed that punishing him would get revenge for the Nazi killings of Czech communists Jan Šverma and Julius Fučík during World War II.

Some historians say that Stalin wanted complete obedience from the leaders of the "People's Democracies" (which were the Eastern European countries allied with the Soviet Union), as well as from leaders in his own country. He threatened to remove "nationalistic communists" from power.

Other historians suggest that the competition between Slánský and Gottwald grew stronger after the 1948 coup. Slánský started to gain more power within the party and put more of his supporters in government jobs. This started to challenge Gottwald's position as president. Stalin supported Gottwald because he thought Gottwald had a better chance of improving Czechoslovakia's economy to produce useful goods for the Soviet Union.

Slánský was seen as weaker because he was considered a "cosmopolitan" figure, meaning he had a broad, international outlook. Gottwald and his friend Antonín Zápotocký, who were popular with the common people, accused Slánský of being part of the wealthy class. Slánský and his allies were also opposed by older party members, the government, and the party's main political group.

The trial of the 14 national leaders began on November 20, 1952. It was held in the Senate of the State Court, with Josef Urválek as the prosecutor. The trial lasted eight days. Just like in the Moscow show trials of the late 1930s, the people on trial admitted they were guilty in court and even asked for a death sentence. Slánský was found guilty of "Trotskyite-Titoist-Zionist activities working for American imperialism." He was publicly executed at Pankrác Prison on December 3, 1952. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered on an icy road outside of Prague.

After His Death

Later, as things changed in Czechoslovakia, Slánský and others who had been punished in these trials were officially cleared of their charges in April 1963. They were fully cleared and declared innocent in May 1968. After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, when Czechoslovakia became a free country, the new president Václav Havel appointed Slánský’s son, who was also named Rudolf, as the Czech ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Rudolf Slánský was the most powerful politician to be executed during the time the Communist Party ruled Czechoslovakia and was influenced by Stalin. After his death, leaders who fell out of favor with the government were treated more gently; they were usually just removed from power and told to retire.

See also

In Spanish: Rudolf Slánský para niños

In Spanish: Rudolf Slánský para niños

- Slánský trial

- Josef Urválek

- Klement Gottwald

- Rudolf Margolius

- Artur London

- Traicho Kostov

- László Rajk

- Josef Smrkovský

- History of anti-Semitism

- Eastern Bloc politics

- Hotel Lux