Sabina Spielrein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sabina Spielrein

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Sheyve (Elisheva) Naftulovna Spielrein

7 November 1885 OS |

| Died | 11 August 1942 (aged 56) Zmievskaya Balka, Rostov-on-Don, Soviet Union

|

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | University of Zurich (M.D., 1911) |

| Known for | death instinct child psychotherapy psycholinguistics |

| Spouse(s) |

Pavel Nahumovich Sheftel

(m. 1912; died 1936) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychotherapy Psychoanalysis |

| Institutions | Rousseau Institute |

| Doctoral advisor | Eugen Bleuler Carl Jung |

| Notable students | Alexander Luria Lev Vygotsky |

Sabina Nikolayevna Spielrein (Russian: Сабина Николаевна Шпильрейн; 7 November 1885 – 11 August 1942) was a Russian physician and one of the first female psychoanalysts. She was a patient, then a student, and later a colleague of Carl Gustav Jung. She also worked with and corresponded with Sigmund Freud.

Sabina Spielrein also worked with the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget. She was a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, teacher, and pediatrician in Switzerland and Russia. During her 30-year career, she wrote over 35 papers in three languages. These papers covered topics like psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, psycholinguistics, and educational psychology.

One of her important works was an essay called "Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being," written in German in 1912. Spielrein was a pioneer in psychoanalysis. She was one of the first to talk about the idea of the death instinct. She also was one of the first psychoanalysts to study schizophrenia in detail. She is now seen as an important and creative thinker.

Contents

Discovering Sabina Spielrein's Life

Early Life and Family (1885–1904)

Sabina was born in 1885 into a wealthy Jewish family in Rostov-on-Don, Russian Empire. Her mother, Eva, came from a family of rabbis and trained as a dentist. Her father, Nikolai, was an agronomist and a successful merchant.

Sabina was the oldest of five children. Her three brothers later became famous scientists. One brother, Isaac Spielrein, was a Soviet psychologist. Another, Jan Spielrein, was a mathematician. From a young age, Sabina was very imaginative. She felt she had a special purpose to achieve great things.

She went to a Froebel school and then the Yekaterinskaya Gymnasium. She was excellent in science, music, and languages. She learned to speak three languages fluently. As a teenager, she decided to study medicine abroad. She earned a gold medal when she finished school.

Hospital Stay and Studies (1904–1911)

After her sister Emilia died suddenly, Sabina's health became difficult. At 18, she had a breakdown with strong emotional reactions. She was admitted to the Burghölzli mental hospital near Zürich in 1904. The hospital director was Eugen Bleuler, and Carl Jung was one of his assistants.

Sabina quickly recovered. By October 1904, she was able to apply for medical school. She also began helping Jung with his research. Jung later mentioned her as one of his first patients. During her time at the hospital, Sabina developed strong feelings for Jung. She stayed at the hospital until June 1905, even after her treatment ended. She worked as an intern with other students.

From 1905 to 1911, she attended medical school at the University of Zurich. She was a top student. Her diaries show she was interested in many subjects, including philosophy, religion, and evolutionary biology. She lived with other Russian Jewish women who were also medical students. Many of them, like Sabina, became interested in psychoanalysis.

Sabina focused on psychiatry in medical school. Many of her friends also became psychiatrists and studied with Freud in Vienna. Politically, Sabina supported socialism.

Sabina wrote her medical dissertation on the language of a patient with schizophrenia. Her work was published in a psychoanalytic journal edited by Jung. This was one of the first studies on schizophrenia published in such a journal. It was also the first doctoral paper by a woman that focused on psychoanalysis. Her study helped people better understand the language of those with schizophrenia. After graduating, she decided to start her own career as a psychoanalyst.

Working with Carl Jung

While in medical school, Sabina continued to help Jung in his lab. She also attended his patient rounds and met him socially. She had strong feelings for him. She imagined having a child with him named Siegfried. Jung tried to understand her feelings.

In 1908, their relationship became more complicated. Jung wrote to Freud about it. Sabina also wrote to Freud, explaining the situation. Sabina's mother became upset and considered reporting Jung. Jung then left his medical job at the Burghölzli hospital.

Sabina and Jung continued to see each other until late 1910. Sabina left Zurich in January 1911. In her diary, she thought about her dream of having Jung's son. She realized it was not possible and would hurt her career.

Some people think Jung's actions were unprofessional. Others believe it was an unexpected result of early psychoanalytic methods. Bruno Bettelheim said that even if Jung's behavior was questionable, it helped Sabina get better. Peter Loewenberg argued it broke professional rules.

Freud at first understood what happened between Jung and Sabina. He saw it as an example of how a therapist's feelings can affect treatment. Later, Freud told Sabina that Jung's behavior played a part in their disagreement. Sabina felt her experiences with Jung were helpful overall. She later wrote to Freud that she found it harder to forgive Jung for leaving the psychoanalytic movement than for their personal relationship.

Some people believe Sabina inspired Jung's idea of the "anima." This is a concept about the inner feminine part of a man. Jung later mentioned a patient who helped him understand this. However, Jung's notes show he was talking about another patient, Maria Moltzer, not Sabina. Still, some historians believe Sabina's relationship with Jung was important for his ideas about the anima.

Career and "Destruction" Paper (1912–1920)

After graduating, Sabina moved to Munich to study art history. She also worked on her paper, "Destruction as the Cause of Coming into Being." In October 1912, she moved to Vienna. She became the second female member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

She presented her paper to the Society in November. It was published the next year. Her paper showed ideas from both Jung and Freud. Freud later mentioned her paper in his famous work, Beyond the Pleasure Principle. He said her ideas helped him develop his concept of the death drive. However, Sabina's idea was different. She saw destruction as serving the purpose of reproduction.

Sabina met Freud several times in 1912 and wrote to him until 1923. She tried to help Freud and Jung resolve their differences. In her "Destruction" paper and throughout her career, she used ideas from many different fields. At 26, Sabina was one of the youngest people to publish her works.

In 1912, Sabina married Pavel Nahumovitch Sheftel, a Russian physician. They moved to Berlin, where Sabina worked with Karl Abraham. Their first daughter, Irma-Renata, was born in 1913. In Berlin, Sabina published nine more papers. One paper discussed children's beliefs about reproduction. Another, called "The Mother-in-Law," talked about the role of mothers-in-law. She also wrote about treating a child with a phobia of animals. This was one of the first reports on child psychotherapy.

When World War I began, she returned to Switzerland. She lived in Zurich and then Lausanne for the rest of the war. Her husband joined his regiment in Kiev, and they were separated for over ten years. Sabina faced hardships during the war. She worked as a surgeon and in an eye clinic. She also received help from her parents. She published two more papers during the war. She also composed music and started writing a novel. She observed her daughter's development, especially in language and play. She continued to develop her ideas, particularly about attachment in children.

Work in Geneva (1920–1923)

In 1920, Sabina attended a psychoanalysis conference in The Hague. She gave a speech on how language begins in childhood. Important people like Sigmund Freud, his daughter Anna Freud, and Melanie Klein were there. She announced she would join the Rousseau Institute in Geneva. This was a leading center for child development.

She worked there for three years with its founder, Édouard Claparède. Jean Piaget also joined the staff. They worked closely together. In 1921, Piaget had an eight-month analysis with her. In 1922, Sabina and Piaget both presented papers at another conference in Berlin. This was a very productive time for her. She published twenty papers between 1920 and 1923.

Her most important paper from this time was a new version of her talk on language. It was called "The origins of the words 'Papa' and 'Mama'." She explained how language develops from a child's natural ability, through interactions with their mother, and then with family and society. Her other papers focused on combining psychoanalysis with studies of child development. Her work during this time likely influenced Piaget and Klein.

In 1923, Sabina decided to go to Moscow. She wanted to help develop psychoanalysis there. She planned to return to Geneva and left her personal papers there. However, she never returned to Western Europe. Her papers were found almost 60 years later by Aldo Carotenuto.

Career in Russia (1923–1942)

When Sabina arrived in Moscow, she was the most experienced psychoanalyst there. She was also well-connected with Western analysts. She became a professor of child psychology at First Moscow University. She also worked in pedology (children study), which combined pediatrics with developmental and educational psychology. She joined the Moscow Psychoanalytic Institute.

She then became involved with a new project called the "Detski Dom" Psychoanalytic Orphanage–Laboratory. This school, founded by Vera Schmidt, aimed to teach children using Freud's ideas. It was called an orphanage but also had children of important Bolsheviks. Children were given a lot of freedom. Sabina helped supervise the teachers. The school closed in 1924.

During Sabina's time in Moscow, both Alexander Luria and Lev Vygotsky studied with her. Her way of combining psychological ideas with observing children likely influenced them. They became leading Russian psychologists.

In 1924 or 1925, Sabina left Moscow and rejoined her husband Pavel in Rostov-on-Don. Pavel had another daughter, Nina, with a Ukrainian woman. Pavel returned to Sabina, and their second daughter, Eva, was born in 1926. For the next ten years, Sabina continued to work as a pediatrician. She did more research, lectured on psychoanalysis, and published in the West until 1931.

In 1929, she strongly defended Freud and psychoanalysis at a conference in Rostov. This was likely the last time such a defense was made before psychoanalysis was banned in Russia. Her paper showed she knew about new ideas in the West. She also talked about the importance of supervision for working with children. She described a way to do short-term therapy when resources were limited. Her niece described her as "a very well mannered, friendly and gentle person. At the same time, she was tough as far as her convictions were concerned." Her husband died in 1936. Sabina made an agreement with Pavel's former partner that if either died, the other would care for their three daughters.

Tragic Death

Sabina and her daughters survived the first German invasion of Rostov-on-Don in November 1941. However, in July 1942, the German army took over the city again. Sabina and her two daughters, aged 29 and 16, were killed by an SS death squad. This happened in Zmievskaya Balka, or "Snake Ravine," near Rostov-on-Don. About 27,000 people, mostly Jewish, were killed there. Most of Sabina's family died in the Holocaust. However, the wives and children of her brothers survived. Today, there are about 14 of their descendants living in Russia, Canada, the United States, and Israel.

Sabina Spielrein's Legacy

After she left Moscow in 1923, Sabina Spielrein was largely forgotten in Western Europe. Her death in the Holocaust made it even harder for her to be remembered. In 1974, letters between Freud and Jung were published. Then, in the 1980s, her personal papers were found and published. This made her name more widely known. However, she was often seen only as a small part of the lives of Freud and Jung. In psychoanalysis, she was usually just a footnote.

In recent years, Sabina Spielrein has been recognized as an important thinker. She influenced Jung, Freud, and Melanie Klein. She also influenced later psychologists like Jean Piaget, Alexander Luria, and Lev Vygotsky. Her work has been important in areas like gender roles, love, women's intuition, the unconscious mind, dream interpretation, and language development in children.

Research in Russia in the 1990s showed that she continued to work actively after leaving Western Europe. In 2003, a book of essays called Sabina Spielrein, Forgotten Pioneer of Psychoanalysis helped create more interest in her. The first detailed biography of her in German, by Sabine Richebächer, showed her relationship with Jung as part of her long career in psychology.

Lance Owens suggests that Sabina's relationship with Jung was important. He believes it helped Jung develop his ideas about love and his concepts of "anima" and "transference."

People who support feminist and relational psychoanalysis are also recognizing her importance. In 2015, Adrienne Harris gave a lecture on "The Clinical and Theoretical Contributions of Sabina Spielrein." She credited Sabina with starting relational psychoanalysis.

Through her work on child analysis, Sabina Spielrein could tell the difference between autistic languages and social languages. She explained how language develops. She also developed an interesting theory about the meaning of sucking and nursing in child development.

The Memorial Museum Sabina Shpilereyn opened in her childhood home, the Spielrein Mansion, in Rostov-on-Don in November 2015.

John Launer's 2015 biography of Sabina Spielrein, written with her family's help, questioned many common ideas about her. He suggests that Jung did not systematically analyze her. He also believes Jung did not see her as more important than his other female partners. Instead, Launer sees her importance as someone who tried to combine psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. She used a biological framework, which was similar to modern ideas from attachment theory and evolutionary psychology.

An English biography by Angela M. Sells, called Sabina Spielrein: The Woman and the Myth, was published in 2017.

Images for kids

-

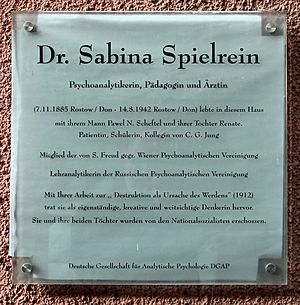

Memorial plaque on the Spielrein Mansion, where Sabina Spielrein lived at 83 Pushkinskaya Steet, Rostov-on-Don. The sign says: "In this house lived the famous student of C. G. Jung and S. Freud, psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein (1885–1942)"

See also

In Spanish: Sabina Spielrein para niños

In Spanish: Sabina Spielrein para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |