Sagebrush Rebellion facts for kids

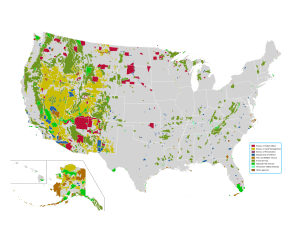

The Sagebrush Rebellion was a movement in the Western United States during the 1970s and 1980s. People in western states wanted big changes to how the U.S. government managed its land. In some western states, the government owns between 20% and 85% of the land!

Supporters of the rebellion wanted states and local groups to have more control. Some even wanted the land to be sold to private owners. Much of this land is covered in a plant called sagebrush, so the movement was named the "Sagebrush Rebellion."

Today, some people still support this idea. They want to use the land for things like ranching, mining, and cutting timber. Others believe the land should be kept for recreation, open spaces, and the natural benefits it provides, like clean air and water.

Why the Sagebrush Rebellion Started

The name "Sagebrush Rebellion" first appeared during arguments about creating new wilderness areas. This happened especially in western states. The U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management had to check large areas of public land. They looked for places that could become protected wilderness.

This process was called "Roadless Area Review and Evaluation" (RARE). It caused a lot of disagreement. Environmental groups wanted more protection. Other groups, like ranchers and miners, wanted to use the land. The first RARE process had problems and was stopped. A second review, RARE II, started in 1977. It looked at over 60 million acres of wild land.

When Ronald Reagan became president in 1980, he supported the movement. He even said, "Count me in as a rebel." This made the Sagebrush Rebellion a big topic. Even though the rebellion slowed down later, some wilderness areas were still created. The movement changed form in 1988 and became known as the "wise use movement."

The idea for a national wilderness system came from a special commission in the 1960s. This group suggested protecting wild rivers and creating a wilderness system. They also wanted to set up a fund to help buy land for recreation.

Much of the land being discussed was covered in sagebrush. Some people wanted to use this land for grazing animals or for off-road vehicles. They did not want it to become protected wilderness. These "rebels" argued that states or private owners should control the land instead of the federal government.

History of Public Lands in the U.S.

There have always been arguments about how the government manages public lands. Different groups, like ranchers, miners, hikers, and conservationists, all have different ideas. Ranchers might say grazing fees are too high. Environmentalists might say grazing rules are not strict enough. Miners want easy access to land, while hikers want untouched nature. Everyone has complaints, and these complaints have a long history.

After the United States became independent, one of the first laws was the Land Ordinance of 1785. This law helped survey and sell land in the western areas that states had given to the new government. Later, the Northwest Ordinance helped organize the Northwest Territory (which includes states like Ohio and Michigan today).

To encourage people to move west, Congress passed the Homestead Acts in 1862. These laws gave small pieces of land to settlers who could live and farm on them for a certain time. Congress also gave huge amounts of land to railroad companies. The idea was that railroads would sell this land to fund their projects.

However, much of the land west of the Missouri River was not good for farming. It had mountains, poor soil, or not enough water. By the early 1900s, the federal government still owned huge parts of most western states. President Theodore Roosevelt then set aside land for forests and special natural areas.

Even after these reserves, a lot of land remained unclaimed. The United States Department of the Interior managed millions of acres in the western states. In 1932, President Herbert Hoover suggested giving these lands to the states. But the states said the land was overgrazed and would be too expensive to manage during the Great Depression. So, the Bureau of Land Management was created to manage much of this land.

The Rebellion Takes Off

After 1932, many bills were proposed to transfer federal lands to western states. But none of them gained much support. One big reason was that the federal government earned a lot of money from mining leases on these lands. Also, people believed that national treasures like Yellowstone National Park and Yosemite National Park should stay under federal control. Few lawmakers wanted to give these famous parks to individual states.

The "rebellion" really started in 1976 with a new law called the Federal Land Policy and Management Act. This law ended homesteading, meaning the federal government would keep control of western public lands. The act aimed to create a system for the Bureau of Land Management to manage land for all users. This included ranching, grazing, and mining. But it also added formal ways to protect the land from these uses.

Senator Orrin Hatch from Utah became involved in 1977. Ranchers and oilmen in Utah complained loudly about federal land rules. Senator Hatch then worked to introduce a bill that would allow states to ask for control over certain land areas. He agreed to keep National Parks and Monuments under federal control.

Senator Hatch introduced his bill in 1979 and again in 1981. Because his bill addressed some of the main concerns, news outlets started to cover it seriously. This led to a two-year public debate in newspapers, on radio, and on television.

In the end, Senator Hatch's bill did not pass. But when Ronald Reagan became president, he appointed James G. Watt as Secretary of the Interior. Watt and his team slowed down or stopped new wilderness designations. By Reagan's second term, the Sagebrush Rebellion was less active, but the arguments about federal land management continued.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |