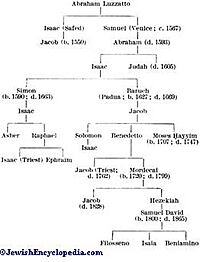

Samuel David Luzzatto facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel David Luzzatto

|

|

|---|---|

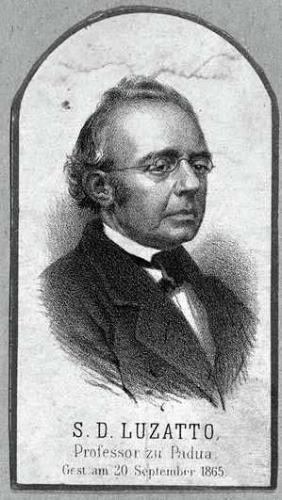

Luzzato, from an 1865 engraving.

|

|

| Born | 22 August 1800 Free City of Trieste, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 30 September 1865 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Italian |

Samuel David Luzzatto (Hebrew: שמואל דוד לוצאטו; 22 August 1800 – 30 September 1865) was a very important Jewish scholar and poet from Italy. People also knew him by his Hebrew acronym Shadal, which is short for his name. He was part of a group called the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement, which focused on studying Jewish history and texts in a scientific way.

Contents

Early Life and Amazing Talent

Samuel David Luzzatto was born in Trieste on August 22, 1800. He passed away in Padua on September 30, 1865. Even as a young boy, he showed incredible talent. He went to a special Jewish school called a Talmud Torah in his hometown. There, he learned about the Talmud, which is a collection of Jewish laws and traditions. His teachers also taught him old and new languages, plus science.

He even studied the Hebrew language at home with his father. His father was a turner (someone who shapes wood or metal), but he was also a very smart Talmud scholar.

Young Scholar's Ideas

When Luzzatto was still a child, he read the Book of Job and thought he could write a better explanation for it. This shows how early he started thinking critically. In 1811, he won a prize: a book by Montesquieu about the Roman Empire. This book really helped him develop his critical thinking skills.

That same year, he started writing a Hebrew grammar book in Italian. He also translated the life story of Aesop into Hebrew. He even wrote notes explaining parts of the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. When he found a mistake in a published version of the Targum (an Aramaic translation of the Bible), it made him want to learn Aramaic.

Tough Times and Continued Learning

At age thirteen, Luzzatto left school, only attending special lectures on the Talmud. While studying, he came up with a new idea: he believed that the special marks for vowels and accents in Hebrew didn't exist when the Talmud was written. He wrote a small book about this idea, which later became a bigger work.

In 1814, Luzzatto faced a very difficult time. His mother died, and he had to do housework, including cooking, and help his father with his work. Despite this, he kept writing. By the end of 1815, he had written many poems. In 1817, he finished a book about Hebrew vowels. He also started a big philosophical and religious work, but only completed part of it.

Luzzatto didn't want to learn a trade like his father. To make money, he gave private lessons, which was hard because he was very shy. After his father died in 1824, he was completely on his own. He continued to teach and write for Jewish magazines. In 1829, he got an important job as a professor at the rabbinical college in Padua. This allowed him to focus fully on his studies and writing.

Studying the Bible in New Ways

At Padua, Luzzatto had more time for his literary work. He wrote down all his thoughts while explaining parts of the Bible to his students. He was one of the first Jewish scholars to study the Syriac language. He believed knowing Syriac was important for understanding the Targum. He also knew a lot about Samaritan Hebrew.

Changing the Bible Text?

Luzzatto was one of the first Jewish scholars who thought it was okay to suggest changes to the text of the Hebrew Bible. Many of his ideas were accepted by other scholars.

He carefully studied the Book of Ecclesiastes. He believed that King Solomon did not write it. Instead, he thought someone named "Kohelet" wrote it much later. Luzzatto thought the author tried to make it seem like Solomon wrote it, but people at the time found out and changed the name to "Kohelet." Today, many scholars agree that Solomon didn't write Ecclesiastes. They often see "Kohelet" as a title, like "Preacher," rather than a person's name.

Isaiah and Prophecy

When it came to the Book of Isaiah, many people thought that chapters 40-66 were written after the Jewish people were exiled to Babylon. However, Luzzatto believed that the entire book was written by the prophet Isaiah. He felt that denying prophets could predict the distant future was wrong. This difference of opinion caused disagreements between Luzzatto and other scholars, like Samuel Judah Löb Rapoport. Luzzatto also disagreed with Isaak Markus Jost because Jost was too focused on logic and not enough on tradition.

Luzzatto's Thoughts on Philosophy

Luzzatto strongly defended traditional Jewish beliefs found in the Bible and Talmud. He was against what he called "philosophical Judaism." This view made him unpopular with some people at the time.

However, his dislike for philosophy wasn't because he didn't understand it. He said he had read many ancient philosophers for 24 years. The more he read, the more he felt they were wrong. He believed philosophers often disagreed with each other and could mislead students. Another main criticism Luzzatto had was that philosophy didn't teach people to be kind to others. He felt traditional Judaism, which he called "Abrahamism," focused on compassion.

Views on Maimonides and Ibn Ezra

For these reasons, Luzzatto praised Maimonides for his great work, the Mishneh Torah. But he also strongly criticized Maimonides for following Aristotelian philosophy. Luzzatto believed this philosophy didn't help Maimonides and caused problems for other Jews.

Luzzatto also criticized Abraham ibn Ezra, another famous Jewish scholar. He said Ibn Ezra's works weren't truly scientific. He thought Ibn Ezra wrote a new book in every town he visited just to make money. Luzzatto claimed Ibn Ezra often used the same ideas but just changed how they were presented. Because of his negative view of philosophy, Luzzatto was also an opponent of Spinoza, a famous philosopher, and often spoke out against his ideas.

Luzzatto's Many Writings

During his long career of over fifty years, Luzzatto wrote a huge number of books and letters. He wrote in Hebrew, Italian, German, and French. He also contributed to most of the Jewish magazines of his time. His letters to other scholars are very detailed and teach a lot about almost any Jewish topic.

His son, Isaiah Luzzatto, published a list of all his father's articles in various magazines.

One important collection of his letters is called Penine Shedal, which means 'The Pearls of Samuel David Luzzatto'. This book has 89 of his most interesting letters. These letters are like scientific papers, covering many subjects such as:

- Letters about books and authors.

- Letters about the Bible and its meaning, including a commentary on Ecclesiastes.

- Letters about Hebrew grammar.

- Letters about history, like discussing how old the Book of Job is.

- Letters about philosophy, including thoughts on dreams and Aristotle.

- Letters about theology, where he argued against Spinoza's ideas.

Works in Hebrew

- Ohev Ger (Padua, 1830): A guide to understanding Targum Onkelos, with notes and a short Syriac grammar.

- Ma'amar ha-Niqqud (Vienna, 1840): A book about Hebrew vowels.

- Bet ha-Otzar (Lemberg, 1847): A collection of essays on the Hebrew language, notes on Bible explanations, and old poetry.

- Iggerot Shadal (Przemysl, 1882): 301 letters published by his son.

- Penine Shedal (Przemysl, 1888): A collection of 89 important letters.

- Sefer Yesode ha-Diqduq (Vienna, 1865): A book on Hebrew grammar.

- Diwan (Lyck, 1864): Extracts from the poems of Judah ha-Levi, with notes.

- Mevo le-Maḥzor (Leghorn, 1856): A historical introduction to the Jewish prayer book.

- Vikkuach 'al ha-Kabbalah (Gorizia, 1852): Dialogues about Kabbalah and the age of Hebrew punctuation.

- Commentary on the Pentateuch (Padua, 1871).

- The Book of Isaiah (Padua, 1855–67): Edited with an Italian translation and a Hebrew commentary.

Works in Italian

- Prolegomeni ad una Grammatica Ragionata della Lingua Ebraica (Padua, 1836): An introduction to a reasoned Hebrew grammar.

- Grammatica della Lingua Ebraica (Padua, 1853–69): A Hebrew grammar book.

- Il Giudaismo Illustrato (Padua, 1854): A collection of essays on Jewish topics.

- Lezioni di Teologia Morale Israelitica (Padua, 1862): Lessons on Jewish moral theology.

- Italian translation of Job (Padua, 1853).

- Italian translation of the Pentateuch and Hafṭarot (Triest, 1858–60).

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |