Santa Clara Church Museum facts for kids

The Santa Clara Museum is located in the old Royal Convent of Santa Clara in the historic center of Bogotá, Colombia. This beautiful building was finished in 1647. It holds a large collection of paintings and sculptures from the 1600s, 1700s, 1800s, and 1900s. The museum is a great example of the Baroque style from the 17th and 18th centuries in Bogotá. It is managed by the Ministry of Culture.

The museum is set up inside one of the old churches that belonged to groups of religious women during the colonial period. It has many old artworks, including pieces by famous artists like Gregorio Vásquez de Arce y Ceballos and Gaspar y Baltazar de Figueroa. You can also see mural paintings on the walls, showing animals, plants, saints, and angels. The museum also hosts modern art shows. These shows help connect old art with today's world and colonial culture.

Contents

History

How it Started

The old church, now the Santa Clara Museum, belonged to the Poor Clares, a group of Franciscan nuns. They started their community in Bogotá in 1629. A Spanish architect named Matías de Santiago built the church. Construction began in 1629 and finished in 1647. The church's inside decoration changed over time. At first, in the 1600s, it had many wall paintings. Later, in the 1700s, wooden panels were added to the walls, and more paintings and sculptures were put in place.

The Archbishop of the city, Fernando Arias de Ugarte, helped fund the church and convent. He wanted to create a place for young women and widows from Bogotá and Spain. On January 7, 1630, a special parade took place. The first 24 nuns arrived at the convent, and the Santa Clara convent officially opened as a closed community.

Life in the Convent

The Santa Clara Convent was a place where many women in Santafé lived their lives, often until they passed away. During the colonial period (1500s to 1700s), parents often sent their daughters to become nuns. Getting a daughter married was very expensive. The bride's parents had to pay for the wedding and a "dowry." A dowry was money and goods given to the future husband to help support his wife. Because of this, families with many daughters and not much money often chose to send them to a convent instead.

Even though convents asked for a "dowry" for new nuns, it was much less than the cost of a marriage dowry. This meant that many colonial women ended up in convents. Convents like Santa Clara received a lot of money and goods, and they had many nuns and new members.

About Saint Clare

The order of Saint Clare was started in 1212 by a rich noblewoman named Clare. She was born in Assisi, Italy, in 1194. The story says that Clare, her sister, and some friends decided to give up their wealth. They wanted to live a life of prayer and poverty, following a young man who taught about humility. This man later became known as Saint Francis of Assisi. The Poor Clares, as they were called, followed the rules of Franciscan life. Over time, their order grew across Europe. Saint Clare was declared a saint in the 1300s. After America was discovered, the Poor Clares came to the New World. In cities like Santafé, their convents welcomed single women or widows who needed a safe place to live, following rules of poverty and purity.

Changes Over Time

In 1863, a law called the Law of Disentailment of Assets of Dead Hands was passed by President Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera. This law meant the government took over the church and convent from the Poor Clares. For a while, the State owned the temple. Later, it was given to the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to manage. Even though the church was returned to its original owners later, the Poor Clares never lived there again.

Today's Museum

In recent years, the Santa Clara Museum has become a key place for colonial culture. It also hosts modern art exhibitions. The museum has been updated to make its history and collections easier to understand for visitors. They use interactive displays to share information about the building and its art. New studies and restoration work have also been done, including on the wall paintings and the old pulpit, which was put back in its original spot in 2014.

Architecture

Building Style

The church's architecture is in the Romanesque style, meaning it has rounded arches. It is a type of Spanish Baroque style, known as "Unadorned Baroque," because its outside doesn't have many decorations. The church has one main room (a nave) and a tower on top. From the outside, you can see a flat roof structure, but inside, the ceiling is a rounded barrel vault. A semicircular arch separates the main altar area (chancel) from the rest of the church.

The floor and walls were made from simple materials of the time, as it was hard to build very fancy things back then. Inside, you can see a second floor, pillars on the walls, and niches in the back that hold religious figures. Even though it's no longer a church, it still has these old features. Its style is very similar to other colonial churches in Bogotá.

This old church is a great example of a female religious temple. It has a single rectangular nave with a thirteen-meter-high vaulted ceiling. There are two entrance doors from the east, which was common for convents. This design followed the rules of the Council of Trent to keep the nuns' living areas private.

Artistic Style

The church is part of the "tempered Baroque" style, which was common in colonial buildings in the New Kingdom of Granada. This style doesn't have complex Baroque shapes in its structure. Instead, it focuses on rich decorations. You can see this in the wall paintings and the many carved and gilded wooden altarpieces. This building mixes elements of Mudéjar, Renaissance, and Baroque styles. This mix shows the unique art of the colonial period and the conditions in Bogotá in the 17th and 18th centuries. Master Matías de Santiago designed the church. It has strong, plain masonry walls with few windows and a brick bell tower in the northeast corner.

Decorated Interior

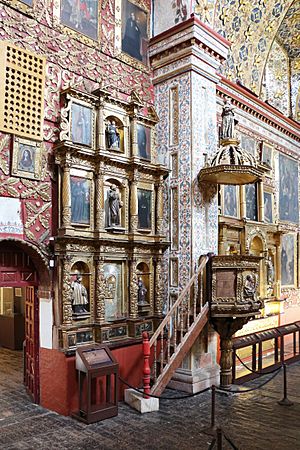

The plain outside of the building is a big contrast to its amazing inside. The vaulted ceiling is covered with golden wooden flowers in the Baroque style. These flowers have blue and yellow spaces, which are the colors of the Immaculate Conception. The walls are completely covered with altarpieces, mural paintings, starry latticework, and a collection of oil paintings. There isn't an empty space anywhere!

The interior uses common colors found in colonial church decorations: red and yellow. In the Catholic Church, red stands for the blood of Christ. Yellow represents the wheat wafer, which symbolizes the body of Christ.

Some parts of the church's inner walls still have original frescoes from the 1600s. These were later covered with red wood and golden stars.

The paintings in the museum are from the 17th and 18th centuries. They show scenes from the Old and New Testaments, with many themes repeated in different ways.

There are 103 paintings, many signed by Gaspar y Baltazar de Figueroa and Gregorio Vásquez de Arce y Ceballos. There are also 24 carved wooden figures from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Examples of Colonial Art

-

Adoration of Saint Clare and Saint Teresa to the Child Jesus Bishop (18th century), by an unknown artist.

Portraits of Nuns

The museum has a collection of portraits of dead abbesses (head nuns). Nuns were often painted at different important times in their lives. This included when they became nuns, when they were chosen as abbesses, when they left to start a new monastery, and when they died.

The words next to the portraits tell about the nun's life and good behavior. The crown of flowers around her head shows that she overcame the difficulties of religious life.

These portraits were meant to decorate the Chapter house of convents. They served as an example for the other Poor Clares. Some were signed by famous painters, but most are by unknown artists.

The Presbytery

This is the most sacred part of the church. It's where the altar is, and where the priest would lead mass. The floor and ceiling here are higher than the rest of the church. This showed that the priest and altar boys were closer to God. In those days, the priest always faced away from the people, looking towards the main altarpiece. Also, the entire mass was spoken in Latin, as decided by the Council of Trent in the mid-1500s.

In the upper part of the presbytery, you can see a collection of paintings of archangels. This is one of the most important collections in the city because of its quality.

The Crypt

There is also a crypt, which is an underground burial place. It was built for the convent's main supporters, Doña María Arias de Ugarte and her husband. They wanted to be buried in the church, which was common at the time because there were no cemeteries. The first cemetery in Bogotá was built in 1830, ordered by Simón Bolívar. He wanted to stop people from being buried in churches. What's interesting about this crypt is its location: it's in the most sacred part of the church, right under the altar and the main altarpiece. It was finished in 1647, the same year the church was officially opened. This is written in old Spanish on the floor covering the crypt.

Main Altarpiece

This altarpiece, along with the choir and main arch, is the most stunning part of the church. It was built around the mid-1600s. It has three main sections and five vertical parts. It is completely carved and covered in gold leaf. Doña María Arias de Ugarte paid for it all. Historical records show it cost 4,200 pesos. The niches hold carved wooden figures, many with costumes made of glued fabric and decorated with special techniques like "stew" and "sgraffito."

Exhibitor

This part was built later, in the 1700s. It's a very Baroque element. Its rich carvings of columns, branches, and birds create a strong contrast with the simpler architecture of the rest of the church.

The Sacristy

This room is next to the main part of the church. It was used to store the priest's special clothes, sacred cups, and other items needed for mass. Now that the church is a museum, this space displays objects from the church's three centuries of history. These objects help visitors understand the church better. According to the rules of the Poor Clares, a nun called the "Sacristina" was in charge of taking care of these sacred items.

Church Clothes and Items

Many of these items were made from gold, silver, and gilded silver. They were created using techniques like carving, embossing, and chiseling. Often, they were decorated with precious stones.

Several of these sacred items are on display to show what the church was like originally. For example, there are two sun-shaped monstrances (holders for the communion wafer) made of gilded silver with semi-precious stones. There's also an incense burner to purify the church with smoke, a small boat-shaped container for incense, and a sprinkler used by the priest to bless with water. You can also see one of the few places where the church's original wall painting is still preserved.

Candlesticks

There are two carved silver candlesticks from the 17th century. They were used with the High Cross. The word "cirial" means a tall candlestick that altar boys carried during masses, evening prayers, and special parades. These candlesticks are shaped like pitchers with twisted handles and carved leaves and cherub heads. They were likely made in Bogotá.

High Cross

This is a processional cross made of carved silver from the 17th century. It was used in important parades and funeral processions. On one side, it has an image of Jesus crucified. On the other side, it has the Blessed Virgin. The base has symbols of Christ's suffering carved into it: the crown of thorns, the column, the nails, the rooster, the spear, and the dice. The ends of the cross are topped with cherubs with open wings.

This is the space between the choirs and the main arch. It was the public area where people who were not nuns could attend mass. These visitors entered the church through the northeast door. The main door was only opened for special processions or to bring out religious statues.

In this area, you can see a small section of the church's original bricks set into the floor. The floor you see now is a modern copy of the original. Most of the church's altarpieces and paintings are found in this central area. Each altarpiece is dedicated to a specific saint, often with other saints around them.

Pulpit Tribune

The pulpit was attached to the right side of the main arch. It was topped by a sounding board with an image of Saint Bonaventure. It has parts from the 17th century, like the inlaid wood on one side. It also has figures of three evangelists: Saint Luke, Saint Mark, and Saint Matthew. These figures were made of plaster and decorated with fine gold and sgraffito work in the 18th century. A wooden ladder, painted with tempera, led up to the pulpit.

The Choir

The choir was a very important and private space for the nuns. Daily services with singing took place here. This was a place for quiet time, prayer, and worship, helping the nuns achieve the spiritual perfection they sought.

Every three years, the abbess (head nun) was chosen in the choir. After the abbess, the choir nun held an important position in the convent. Nuns who were especially respected for their good deeds were often buried in the lower part of the choir. In the Santa Clara choir, the beautiful Mudéjar starry pattern in the remaining original lattice shows how private this space was.

Nuns' Choirs

The design of nuns' choirs changed based on how grand and wealthy each church was. It also depended on the money available, and the creativity of the builders, carvers, and painters. Spain and Portugal have amazing examples of these choirs, and in the New World, especially in Querétaro, Mexico. Choirs were sacred, enclosed spaces, usually made up of these parts:

- Bars: These were in the upper and lower choir. They symbolized the nuns' confinement. They were usually made of wood or thick wrought iron, sometimes doubled.

- Craticula: This was a small carved wooden window, usually one or two. Nuns received communion through it. It was often next to the lower choir's bars. This piece was part of a larger structure that separated the nuns' private area from the rest of the church.

- Tribune: There could be one or more. These were platforms used for musical instruments, as in Santa Clara, or for sick nuns to attend services.

- Fan: This was a large, semicircular element that topped the high choir. It showed arabesques, carved leaves, and latticework. Often, a large Christ figure in the center seemed to protect the whole area.

In Mexico, nuns' choirs were richly decorated with carvings and paintings. Inside the high choir, there were stalls for the nuns to rest and sing during services. In nuns' churches, choirs were usually at the back of the church, but sometimes they were near the main altar. They always connected to the convent.

See also

In Spanish: Museo Iglesia de Santa Clara para niños

In Spanish: Museo Iglesia de Santa Clara para niños

- List of buildings in Bogotá