Santa Susana Field Laboratory facts for kids

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL), also known as Rocketdyne, is a large area of land in Ventura County, Southern California. It's located in the Simi Hills, between the cities of Simi Valley and Los Angeles.

For many years, from 1949 to 2006, SSFL was a place where scientists and engineers worked on important projects for the United States space program. They developed and tested rocket engines for rockets that went into space. They also worked on nuclear reactors from 1953 to 1980 and researched how to use liquid metals for energy from 1966 to 1998.

About ten small nuclear reactors operated at SSFL. One of them, the Sodium Reactor Experiment, was the first reactor in the U.S. to create electricity for homes and businesses. It also had a partial meltdown, which means its core got too hot and was damaged. At least four of these experimental reactors had accidents. Unlike modern power plants, these experimental reactors did not have strong concrete buildings around them to contain any releases.

The research and testing stopped in 2006. Because of all the rocket testing and nuclear work, the site became "significantly contaminated." This means there are harmful chemicals and radioactive materials in the soil and water. A big cleanup effort is happening now. People living nearby are very concerned and want the site to be cleaned up thoroughly. They have reported higher rates of illnesses, including cancer, though scientists are still studying if there's a direct link between these illnesses and the contamination.

Contents

What is the Santa Susana Field Laboratory?

Since 1947, different companies and government groups have used the Santa Susana Field Laboratory. One of the first was Rocketdyne, which was part of a company called North American Aviation. Rocketdyne designed and tested many successful liquid rocket engines. These engines were used in famous rockets like the Saturn V, which took astronauts to the Moon during the Apollo missions, and the engines for the Space Shuttle Main Engine.

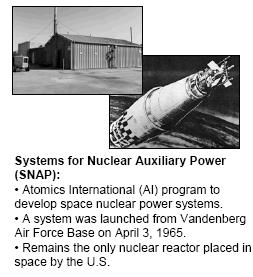

Another part of North American Aviation, called Atomics International, used a special area of SSFL. Here, they built and ran the first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States. They also tested small nuclear reactors, including the SNAP-10A, which was the first nuclear reactor launched into space by the U.S. Atomics International also ran the Energy Technology Engineering Center for the U.S. Department of Energy at the site.

In 1996, The Boeing Company became the main owner of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory and later closed the site.

Three California state agencies and three federal agencies have been carefully checking the environmental effects of the site's past activities since 1990. There have been concerns about how waste was handled, leading to lawsuits and groups working to make sure the cleanup is done right.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory is also home to the Burro Flats Painted Cave, which is a historic site with ancient Native American drawings. These drawings are considered "the best preserved Indian pictograph in Southern California." Several streams that flow into the Los Angeles River start on the SSFL property, including Bell Creek.

History of the Site

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory was a United States government facility. It was used to develop and test nuclear reactors and powerful rockets like those for the Apollo missions. The site was chosen in 1947 because it was far away from people. This was important because the work was considered dangerous and noisy. However, over the years, more people moved to Southern California, and houses were built closer to the site.

The SSFL is divided into different sections: Areas I, II, III, and IV, plus two buffer zones. Areas I, II, and III were used for testing rockets and missiles. Area IV was mainly for nuclear reactor experiments.

Rocket Engine Development

After World War II, North American Aviation started developing rocket engines that used liquid fuel. Their Rocketdyne division designed and tested many engines at SSFL. These included engines for early missiles like the Redstone, Jupiter, and Thor. They also developed engines for the Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missile.

Later, Rocketdyne designed and tested the J-2 engine. This engine used liquid oxygen and hydrogen and was used in the second and third stages of the Saturn V rocket, which was crucial for the Moon missions. While the J-2 was tested at SSFL, the much larger F-1 engine for the first stage of the Saturn V was tested in the desert. This was because the F-1 was too loud and powerful to be tested so close to populated areas.

Nuclear and Energy Research

The Atomics International Division of North American Aviation used SSFL Area IV to build the first commercial nuclear power plant in the U.S. They also tested and developed the SNAP-10A, which was the first nuclear reactor launched into space by the United States. Atomics International also ran the Energy Technology Engineering Center for the U.S. government. As interest in nuclear power changed, Atomics International began working on other energy projects and eventually stopped designing nuclear reactors.

Sodium Reactor Experiment

The Sodium Reactor Experiment (SRE) was an experimental nuclear reactor that operated at the site from 1957 to 1964. It was the first commercial power plant in the world to have a partial core meltdown. This incident was kept quiet for many years by the U.S. Department of Energy. The reactor and its systems were removed in 1981, and the building was torn down in 1999.

Energy Technology Engineering Center

The Energy Technology Engineering Center (ETEC) was a government-owned facility within Area IV of SSFL. ETEC focused on testing parts designed to transfer heat from nuclear reactors using liquid metals instead of water or gas. It operated from 1966 to 1998. The ETEC site is now closed, and its buildings are being removed as part of the environmental cleanup.

Accidents and Site Contamination

Over the years, about ten small nuclear reactors operated at SSFL. There were also other facilities, like a pit where sodium-coated objects were burned, and labs for making nuclear fuel. A "Hot Lab" was used to handle very radioactive materials remotely.

The Hot Lab had several fires involving radioactive materials. For example, in 1957, a fire there caused "massive contamination."

At least four of the ten nuclear reactors had accidents:

- In March 1959, the AE6 reactor released some radioactive gases.

- In July 1959, the SRE had a power surge and a partial meltdown. This released radioactive gases into the air.

- In 1964, the SNAP8ER reactor had damage to 80% of its fuel.

- In 1969, the SNAP8DR reactor had similar damage to one-third of its fuel.

In 1971, a radioactive fire happened involving a liquid metal coolant that was contaminated with radioactive materials. The experimental reactors at SSFL did not have the large concrete domes that surround modern nuclear power plants to contain accidents.

Sodium Burn Pits

The sodium burn pit was an open area where workers cleaned parts that had been in contact with sodium. However, it was also used to burn items that were contaminated with radioactive and chemical materials, which was against safety rules. A former SSFL worker named James Palmer said that 22 out of 27 men on his crew died of cancers. He also described how the water in nearby ponds was so polluted that fish died.

In 2002, an official from the Department of Energy described how waste was sometimes handled in the past. Workers would put barrels of radioactive sodium into a pond and then shoot them with rifles. This would make the barrels explode and release their contents into the air. Since then, the pit has been cleaned up, with 22,000 cubic yards of soil removed.

In 1994, two scientists were killed when chemicals they were illegally burning in open pits exploded. After an investigation, three Rocketdyne officials admitted to illegally storing explosive materials.

2018 Woolsey Fire

The 2018 Woolsey Fire started at SSFL and burned about 80% of the site. After the fire, health officials checked the area. The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health found "no discernible level of radiation" in the tested area. The California Department of Toxic Substances Control also said that the fire did not affect previously handled radioactive and hazardous materials. However, some groups, like Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles, said that when contaminants burn and become airborne, there is a risk of increased exposure for people living nearby.

In 2020, the California Department of Toxic Substances Control stated that the fire did not release contaminants into nearby communities. A 2021 study found that most dust, ash, and soil samples after the fire were normal. However, two locations had high levels of radioactive materials linked to the Santa Susana Field Laboratory.

Health Concerns

In October 2006, a group of independent scientists looked at the data from SSFL. They estimated that contamination at the facility might have led to about 260 cancer-related deaths. They also found that the SRE meltdown released much more radioactivity into the environment than the Three Mile Island accident. This was because the SRE did not have proper containment structures like modern nuclear power plants.

Studies between 1988 and 2002 suggested that people living within 2 miles of the lab were 60% more likely to be diagnosed with certain cancers compared to those living 5 miles away. However, the researcher noted that the lab was not necessarily the cause.

Cleanup Efforts

During its many years of operation, SSFL used highly toxic chemicals for rocket engine tests and cleaning. There were also nuclear research activities and at least four nuclear accidents. All of this made SSFL a very contaminated site, affecting the surrounding areas. A complex cleanup project is now underway. The process of figuring out how much contamination there is, what cleanup standards to meet, what methods to use, and how long it will take is still being discussed.

Cleanup Standards

In May 2007, a Federal Court ruled that the Department of Energy (DOE) had not been cleaning up the site to the right standards. The court said that the site would need to be cleaned up to much higher standards if the DOE wanted to give the land to Boeing, which might then develop it for homes. The judge noted that the lab is "only miles away from one of the largest population centers in the world."

Water Runoff Issues

In July 2007, the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board suggested a large fine against Boeing. This was for 79 violations of water laws between October 2004 and January 2006. Wastewater and stormwater runoff from the lab had high levels of harmful substances like chromium, dioxin, lead, and mercury. This contaminated water flowed into Bell Creek and the Los Angeles River, which was against their permit.

Parkland Agreement

In October 2007, Boeing announced an agreement with California officials. Nearly 2,400 acres of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory land would become state parkland. This agreement means the land will be protected as open space and cannot be used for homes or businesses.

Recent Cleanup Developments

SB 990

California state law SB 990, passed in 2007, set strict standards for the site's cleanup. Boeing, the Department of Energy (DOE), and NASA are the parties responsible for the cleanup and need to agree to these standards.

Boeing

Boeing challenged the law in court but lost. They claim they will clean up the site, but to levels that are less strict than those in SB 990.

DOE and NASA

In September 2010, the DOE and NASA agreed to meet the strict cleanup standards set by SB 990. They also agreed to pay for all the cleanup costs for their parts of the site. This was a big step forward. In 2014, NASA released a plan to demolish all structures and clean up contaminated soil and groundwater. They found that more soil needed to be removed than first thought, so an updated report was made in 2019.

Demolition of old buildings was planned to start in 2015. The rocket test stands, which are more complex, would follow. Some historically important buildings might remain if cleanup goals can still be met. The cleanup was projected to be finished in 2017. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Energy announced plans to demolish 13 of 18 remaining structures. In 2020, an agreement was made to demolish 10 of the most contaminated buildings.

Community Involvement

A "Community Advisory Group" (CAG) was formed in 2012. This group advises on the cleanup. The SSFL CAG suggests a cleanup that focuses on risk, aiming for a standard that minimizes digging and soil removal. However, some believe the CAG has a conflict of interest because it receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, and some members used to work for Boeing or its parent company.

Images for kids

-

Aerial view of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory in the Simi Hills, with the San Fernando Valley and San Gabriel Mountains beyond to the east. The Energy Technology Engineering Center site is in the flat Area IV at the lower left, with the Rocket Test Field Laboratory sites in the hills at the center. (Spring 2005)

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |